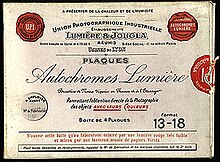

Autochrome Lumière

[citation needed] Unlike ordinary black-and-white plates, the Autochrome was loaded into the camera with the bare glass side facing the lens so that the light passed through the mosaic filter layer before reaching the emulsion.

[citation needed]To create the Autochrome color filter mosaic, a thin glass plate was first coated with a transparent adhesive layer.

The dyed starch grains were graded to between 5 and 10 micrometers in size and the three colors were thoroughly intermingled in proportions which made the mixture appear gray to the unaided eye.

It was found that the application of extreme pressure would produce a mosaic that more efficiently transmitted light to the emulsion, because the grains would be flattened slightly, making them more transparent, and pressed into more intimate contact with each other, reducing wasted space between them.

The 1906 U.S. patent describes the process more generally: the grains can be orange, violet, and green, or red, yellow, and blue (or "any number of colors"), optionally with black powder filling the gaps.

Experimentations within the early twentieth century provided solutions to many issues, including the addition of screen plates, a yellow filter designed to balance the blue, and adjustments to the size of the silver halide crystals to allow for a broader spectrum of colour and control over the frequency of light.

[8] Because the presence of the mosaic color screen made the finished Autochrome image very dark overall, bright light and special viewing arrangements were needed for satisfactory results.

Projection required an extremely bright and therefore hot light source (a carbon arc or a 500-watt bulb were typical) and could visibly "fry" the plate if continued for more than two or three minutes, causing serious damage to the color.

The lamination of the grains, varnish, and emulsion makes autochrome plates susceptible to deterioration with each layer being vulnerable to changes in environment such as moisture, oxidation, cracking, or flaking as well as physical damage from handling; solutions involve conservative lighting conditions, chemical-free materials, medium-range humidity control of between 63 and 68 degrees Fahrenheit in a well integrated preservation plan.

The dyed starch grains are somewhat coarse, giving a hazy, pointillist effect, with faint stray colors often visible, especially in open light areas such as skies.

[citation needed] Although difficult to manufacture and fairly expensive, Autochromes were relatively easy to use and were immensely popular among enthusiastic amateur photographers, at least among those who could bear the cost and were willing to sacrifice the convenience of black and white hand-held snapshots."

Not only did the need for diascopes and projectors make them extremely difficult to publicly exhibit, they allowed little in the way of the manipulation much loved by aficionados of the then-popular Pictorialist approach.

Although these soon completely replaced glass plate Autochromes, their triumph was short-lived, as Kodak and Agfa soon began to produce multi-layer subtractive color films (Kodachrome and Agfacolor Neu respectively).

[citation needed] In the U.S. Library of Congress's huge collection of American Pictorialist photographer Arnold Genthe's work, 384 of his autochrome plates were among the holdings as of 1955.

[17] The George Eastman Museum in Rochester, N.Y. has an extensive collection of early colour photography, including Louise Ducos Du Hauron's earliest autochrome images and materials used by the Lumière brothers.

Both the autochrome photograph of the Humphrey children and the diascope mirror viewing device, which closes into itself in a leather-bound case similar in size and appearance to a book, are well preserved and still viewable in 2015.