Halftone

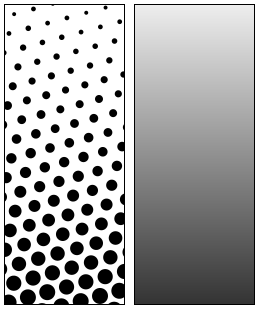

Halftone is the reprographic technique that simulates continuous-tone imagery through the use of dots, varying either in size or in spacing, thus generating a gradient-like effect.

[1] Where continuous-tone imagery contains an infinite range of colors or greys, the halftone process reduces visual reproductions to an image that is printed with only one color of ink, in dots of differing size (pulse-width modulation) or spacing (frequency modulation) or both.

This reproduction relies on a basic optical illusion: when the halftone dots are small, the human eye interprets the patterned areas as if they were smooth tones.

At a microscopic level, developed black-and-white photographic film also consists of only two colors, and not an infinite range of continuous tones.

[2] The semi-opaque property of ink allows halftone dots of different colors to create another optical effect: full-color imagery.

Previously most newspaper pictures were woodcuts or wood-engravings made from hand-carved blocks of wood that, while they were often copied from photographs, resembled hand drawn sketches.

[6] The New York Daily Graphic would later publish "the first reproduction of a photograph with a full tonal range in a newspaper" on March 4, 1880 (entitled "A Scene in Shantytown") with a crude halftone screen.

[5] Shortly afterwards, Ives, this time in collaboration with Louis and Max Levy, improved the process further with the invention and commercial production of quality cross-lined screens.

In the 1860s, A. Hoen & Co. focused on methods allowing artists to manipulate the tones of hand-worked printing stones.

When different screens are combined, a number of distracting visual effects can occur, including the edges being overly emphasized, as well as a moiré pattern.

The general idea is the same, by varying the density of the four secondary printing colors, cyan, magenta, yellow, and black (abbreviation CMYK), any particular shade can be reproduced.

To do this the industry has standardized on a set of known angles, which result in the dots forming into small circles or rosettes.

In the 1980s, halftoning became available in the new generation of imagesetter film and paper recorders that had been developed from earlier "laser typesetters".

[14] Early laser printers from the late 1970s onward could also generate halftones but their original 300 dpi resolution limited the screen ruling to about 65 lpi.

Each equal-sized cell relates to a corresponding area (size and location) of the continuous-tone input image.

Within each cell, the high-frequency attribute is a centered variable-sized halftone dot composed of ink or toner.

From a suitable distance, the human eye averages both the high-frequency apparent gray level approximated by the ratio within the cell and the low-frequency apparent changes in gray level between adjacent equally spaced cells and centered dots.

The fixed location and size of these monochrome pixels compromises the high-frequency/low-frequency dichotomy of the photographic halftone method.

Digital halftoning based on some modern image processing tools such as nonlinear diffusion and stochastic flipping has also been proposed recently.

[15] The most common method of creating screens, amplitude modulation, produces a regular grid of dots that vary in size.

There are many halftoning algorithms which can be mostly classified into the categories ordered dithering, error diffusion, and optimization-based methods.

The most straightforward way to remove the halftone patterns is the application of a low-pass filter either in spatial or frequency domain.

Decomposing the halftone image into its wavelet representation allows to pick information from different frequency bands.

Another possibility for inverse halftoning is the usage of machine learning algorithms based on artificial neural networks.

Convolutional neural networks are well-suited for tasks like object detection which allows a category based descreening.

Generating the descreened image is fast compared to iterative methods because it requires a lookup per pixel.