Avestan period

[11] The Old Avestan material is found in the Staota Yesniia, the central part of Zoroastrinian High Liturgies like the Yasna and the Visperad.

The Staota Yesniia consists of the Gathas, the Yasna Haptanghaiti, and a number of manthras, namely the Ashem Vohu, the Ahuna Vairya and the Airyaman ishya.

[13] A few texts are sometimes considered to be in pseudo Old Avestan, namely the Yenghe hatam manthra and some parts of the Yasna Haptanghaiti.

[15] The Young Avestan material is much larger, but also more varied and may reflect a longer time of composition and transmission, during which the different texts may have been constantly updated and revised.

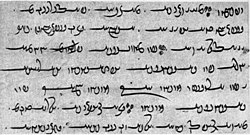

[23] Apart from such changes and redactions, the extant Old and Young Avestan texts were then passed on orally for several centuries until they were eventually set down in writing during the Sassanid period.

This is due to the fact that a large portion of the Avesta became lost after the Islamic conquest of Iran and the subsequent marginalisation of Zoroastrianism.

[30] It is generally accepted that these place names are concentrated in the eastern parts of Greater Iran centered around the modern day countries of Afghanistan and Tajikistan.

The discussion around this chronology, therefore, strongly focused on the validity of these accounts, with scholars like Walter Bruno Henning, Ilya Gershevitch, and Gherardo Gnoli having made arguments in its favor whereas others have criticized them.

First, the numerous and strong parallels between Old Avestan and the early Vedic period, which itself is assumed to reflect the second half of second millennium BCE.

[41] For example, both Old Avestan and the language of the Rigveda are still very close, suggesting only a limited time frame had passed since they split off from their common Proto-Indo-Iranian ancestor.

[43][44] Second, the Young Avestan texts lack any discernible Persian or Median influence indicating that the bulk of them was produced before the rise of the Achaemenid Empire.

[49][50][51][52] Modern archaeology has unearthed a wealth of data on settlements and cultures in Central Asia and Greater Iran during the Avestan period, i.e., from the Middle Bronze Age to the rise of the Achaemenids.

During the Bronze Age, Southern Central Asia was home to a prominent urban civilization with long-range trade networks to the south.

However, the middle of the second millennium BCE saw major transformations of this area, with the urban centers being replaced by smaller settlements and a shift to a mixed agricultural-pastoral economy with strong ties to the northern steppe regions.

In addition, camelophoric names like Zarathustra and Frahaostra (uštra, 'camel') show the importance of the Bactrian camel, an animal well adapted to the harsh conditions of the steppe and desert regions of Central Asia.

In addition, montane transhumance of cattle, sheep and goats is practiced and each September a feast similar to Almabtrieb (ayāθrima, driving in) is celebrated, after which the livestock is kept in stables during the winter.

[72] Young Avestan society has similar concentric circles of kinship; the family (nmāna), clan (vīs) and the tribe (zantu).

[73] Despite the same division and the same general terms existing in the Vedic society, the specific names for priests, warriors and commoners are different, which may reflect an independent development of the two systems.

[77] In the Young Avestan society, a number of features associated with Zoroastrianism, like the killing of noxious animals, purity laws, the veneration of the dog, and a strong dichotomy between good and evil, are already fully present.

[74] Great emphasis is placed on procreation, and sexual activities that are not conducive to this goal, such as masturbation, homosexuality and prostitution, are strongly condemned.

[83] Yet despite the close proximity of the Avestan and Vedic Arya, it is not clear if these two peoples had any continued interaction, since neither the Avesta nor the Vedas make any unambiguous reference to the other group.

On the other hand, the Avesta mentions a number of people with whom the Arya were in continuous contact with, namely the Turiia, Sairima, Sainu and Dahi.

There are no direct sources on the religious beliefs of the Iranian peoples before Zarathustra, but scholars can draw on allusions found in the Zoroastrian texts as well as use comparisons with the Vedic religion of Ancient India.

There are a number of similarities between Zoroastrianism and the Vedic religion in the ritual sphere, suggesting they go back to the shared Indo-Iranian past.

[89] The exact nature of Zarathustra's reforms remains a subject of debate among scholars, but the hostility experienced by the early Zoroastrian community suggests they were substantial.

On the other hand, scholars such as Ilya Gershevitch have argued that the Young Avestan Zoroastrianism is a syncretistic religion that formed from the fusion of Zarathustra's monotheisitc/dualistic teachings with the practices of polytheistic Iranian communities that were absorbed as the faith spread.

This is for instance expressed in the Mihr Yasht, which describes how Mithra is crossing Mount Hara and surveys the Airyoshayana, i.e., the lands inhabited by the Airiia, and the seven regions(Yt.

Characters like Yima, Thraetaona and Kauui Usan have counterparts in the Vedic Yama, Trita, and Kavya Ushanas and therefore must go back to the common Indo-Iranian period.

One example is a possible memory of the kinship between the Iranians peoples expressed through three sons of Thraetaona, namely Iraj (Airiia), Tur (Turiia) and Sarm (Sairima).

The impact of the Avestan period on Iranian literary tradition was overall so substantial that Elton L. Daniel concluded "Its stories were so rich, detailed, coherent, and meaningful that they came to be accepted as records of actual events - so much so that they almost totally supplanted in collective memory the genuine history of ancient Iran.