Avian brain

Birds possess large, complex brains, which process, integrate, and coordinate information received from the environment and make decisions on how to respond with the rest of the body.

The telencephalon is dominated by a large pallium, which corresponds to the mammalian cerebral cortex and is responsible for the cognitive functions of birds.

Some birds exhibit strong abilities of cognition, enabled by the unique structure and physiology of the avian brain.

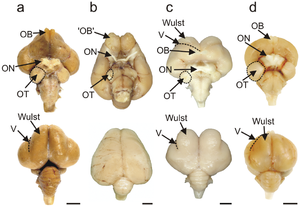

[1] The pallial domain is divided into two main parts: the Wulst, or hyperpallium, at the dorsal surface of the pallium, and the dorso-ventricular ridge, which comprises the nidopallium, arcopallium, and archipallium.

Neural activity in the nidopallium caudolaterale is correlated with rewards, rules, categories, and information held in the memory.

[6] Research through the 1960s demonstrated that the basal ganglia of birds occupied only the ventromedial telencephalon and not the entire forebrain, a historically held belief.

[7] The cerebellum is a relatively conservative part of the brain, with circuitry tending to be similar across different types of vertebrates.

For instance, in birds that perform much manipulation with the beak, like crows, woodpeckers, and parrots, there is an expansion of the visual part of the cerebellum.

[10] In general, the folding patterns of the cerebellum in birds reflect differences of behaviour, as well as variations in skull shape constraining cerebellar development and sensory and sensorimotor requirements of animals living disparate lifestyles.

The large numbers of neurons in the avian brain are enabled by relatively low specific energy demands.

It is not yet known why avian brains require so much less glucose, but two contributing factors, neuron size and body temperature, have been posited by researchers.

Additionally, the higher temperatures of bird brains, reaching 42 °C (108 °F) in pigeons, also facilitate lower energy consumption.

The nidopallium caudolaterale of the avian brain, responsible for goal-directed action, has been found in crocodylians, the closest living relatives of birds, separated evolutionarily by 245 million years.

Several Mesozoic avialans have brain endocasts: Archaeopteryx, which is not always classified as an avialan (closer to modern birds than to Dromaeosaurus),[14] Navaornis, an enantiornithean from the late Cretaceous,[17] Cerebavis, an incomplete specimen which lacks a hyperpallium and whose classification is unclear, Ichthyornis, and MPM-334-1, a basicranium that belonged to an eighty-million-year old enantiornithine bird, preserving the hindbrain.

Indeed, several oviraptorosaurs, as well as the troodontine Zanabazar and the jinfengopterygine troodontid[20] IGM100/1126, possess brains larger relative to their body size than Archaeopteryx.

Other elements of the cranial anatomy of Archaeopteryx are likewise similar to those of other maniraptoran dinosaurs, suggesting that those animals may also have had the requisite neurological facilities for flight.

[22] As seen in brain endocasts of Navaornis, the telencephalon is expanded mediolaterally compared to in Archaeopteryx and non-avialan pennaraptorans, but not to the same degree as in modern birds, and the cerebellum is relatively small.

[14] Three major grade shifts in brain-to-body ratio are inferred by scientists to have taken place in the evolution of birds from basal Paraves to the base of crown Neoaves.

In the clade Neoaves, comprising all birds save fowl and paleognaths, the brain-to-body ratio increases, but this is driven primarily by a decrease in average body size.

One, in Afroaves, is made up of the owls, which have large brains evolved for visual acuity, and the Accipitriformes, including hawks and eagles.

[23] Some of the largest brain-to-body ratios in birds, especially of the telencephalon, that part of the brain responsible for cognition, are found in the Psittaciformes (parrots) and Corvidae (crows, ravens, jays, magpies, and allies), both members of the Australaves.

[23] In contrast to what is currently thought to be relatively few grade changes in the brain-to-body ratio of birds in the Mesozoic, researchers have found that nine such shifts took place in the Paleocene, possibly as a response to the K-Pg extinction event.

Despite this, birds such as corvids and parrots display intellectual behaviour that are comparable to those of highly intelligent mammals like the great apes.

Scientists believe that this is an example of convergent evolution, wherein radically different gross structures evolved towards connectional similarities that produced comparable results.

[27] The prefrontal cortex of mammals, which is highly involved in the processes that support complex learning, may have an analogue in birds in the form of the nidopallium caudolaterale.

At the turn of the 20th century, the German neurologist Ludwig Edinger devised a theory of vertebrate cerebral evolution that soon became the dominant scientific view.

Following a linear model of evolution, Ariëns-Kappers promoted the idea that brain structures were gained in sequence in evolutionary lineages, called an accretionary theory.

[30] For years, too, scientists assumed that birds were not capable of advanced thought, as their brains were perceived to be devoid of complex pallial structures.

In fact, neurologists believed that birds were creatures that acted on instinct rather than on any sort of thought, and that they were highly unintelligent.

[29] Research into bird cognition, behaviour, and anatomy, as well as into the brain, specifically, it became apparent that the traditional accretionary view of vertebrate telencephalic evolution was incorrect.