Ayn Rand

Rand was born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum on February 2, 1905, into a Jewish bourgeois family living in Saint Petersburg, which was then the capital of the Russian Empire.

Her father's pharmacy was nationalized,[9] and the family fled to Yevpatoria in Crimea, which was initially under the control of the White Army during the Russian Civil War.

[10] After graduating high school there in June 1921,[11] she returned with her family to Petrograd (as Saint Petersburg was then named),[e] where they faced desperate conditions, occasionally nearly starving.

Rand questioned her about American history and politics during their many meetings, and gave Paterson ideas for her only non-fiction book, The God of the Machine.

[65] The drug helped her to work long hours to meet her deadline for delivering the novel, but afterwards she was so exhausted that her doctor ordered two weeks' rest.

[71] In 1947, during the Second Red Scare, she testified as a "friendly witness" before the United States House Un-American Activities Committee that the 1944 film Song of Russia grossly misrepresented conditions in the Soviet Union, portraying life there as much better and happier than it was.

They informed both their spouses, who briefly objected, until Rand "sp[u]n out a deductive chain from which you just couldn't escape", in Barbara Branden's words, resulting in her and O'Connor's assent.

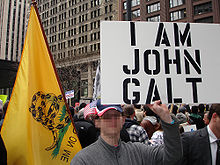

The novel's hero and leader of the strike, John Galt, describes it as stopping "the motor of the world" by withdrawing the minds of individuals contributing most to the nation's wealth and achievements.

[67][87] Atlas Shrugged was her last completed work of fiction, marking the end of her career as a novelist and the beginning of her role as a popular philosopher.

These included supporting abortion rights,[101] opposing the Vietnam War and the military draft (but condemning many draft dodgers as "bums"),[102][103] supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War of 1973 against a coalition of Arab nations as "civilized men fighting savages",[104][105] claiming European colonists had the right to invade and take land inhabited by American Indians,[105][106] and calling homosexuality "immoral" and "disgusting", despite advocating the repeal of all laws concerning it.

[115][116] Rand's younger sister Eleonora Drobisheva (née Rosenbaum, 1910–1999) visited her in the US in 1973 at the former's invitation, but did not accept her lifestyle and views, as well as finding little literary merit in her works.

Beyond We the Living, which is set in Russia, this influence can be seen in the ideas and rhetoric of Ellsworth Toohey in The Fountainhead,[142] and in the destruction of the economy in Atlas Shrugged.

He accused Rand of supporting a godless system (which he related to that of the Soviets), claiming, "From almost any page of Atlas Shrugged, a voice can be heard ... commanding: 'To a gas chamber—go!'".

[158] Philosopher Sidney Hook likened her certainty to "the way philosophy is written in the Soviet Union",[159] and author Gore Vidal called her viewpoint "nearly perfect in its immorality".

[164] Several academic book series about important authors cover Rand and her works,[m] as do popular study guides like CliffsNotes and SparkNotes.

"[167] In 2019, Lisa Duggan described Rand's fiction as popular and influential on many readers, despite being easy to criticize for "her cartoonish characters and melodramatic plots, her rigid moralizing, her middle- to lowbrow aesthetic preferences ... and philosophical strivings".

[187] Several authors, including Robert Nozick and William F. O'Neill in two of the earliest academic critiques of her ideas,[188] said she failed in her attempt to solve the is–ought problem.

[192] Rand opposed collectivism and statism,[193] which she considered to include many specific forms of government, such as communism, fascism, socialism, theocracy, and the welfare state.

[207] In a 1959 interview with Mike Wallace, when asked where her philosophy came from, she responded: "Out of my own mind, with the sole acknowledgement of a debt to Aristotle, the only philosopher who ever influenced me.

"[208] In an article for the Claremont Review of Books, political scientist Charles Murray criticized Rand's claim that her only "philosophical debt" was to Aristotle.

[217] Rand's views also may have been influenced by the promotion of egoism among the Russian nihilists, including Chernyshevsky and Dmitry Pisarev,[218][219] although there is no direct evidence that she read them.

[220][221] Rand considered Immanuel Kant her philosophical opposite and "the most evil man in mankind's history";[222] she believed his epistemology undermined reason and his ethics opposed self-interest.

[239] In one essay, political writer Jack Wheeler wrote that despite "the incessant bombast and continuous venting of Randian rage", Rand's ethics are "a most immense achievement, the study of which is vastly more fruitful than any other in contemporary thought".

"[242] Writing in the 1998 edition of the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, political theorist Chandran Kukathas summarized the mainstream philosophical reception of her work in two parts.

[266][267] Throughout her life she was the subject of many articles in popular magazines,[268] as well as book-length critiques by authors such as the psychologist Albert Ellis[269] and Trinity Foundation president John W.

[239] Rand or characters based on her figure prominently in novels by American authors,[270] including Kay Nolte Smith, Mary Gaitskill, Matt Ruff, and Tobias Wolff.

[281][282] Rand is often considered one of the three most important women (along with Rose Wilder Lane and Isabel Paterson) in the early development of modern American libertarianism.

[288] She faced intense opposition from William F. Buckley Jr. and other contributors to the conservative National Review magazine, which published numerous criticisms of her writings and ideas.

[291][292][293] She has influenced some conservative politicians outside the U.S., such as Sajid Javid in the United Kingdom, Siv Jensen in Norway, and Ayelet Shaked in Israel.

[307][308] In 2001, historian John P. McCaskey organized the Anthem Foundation for Objectivist Scholarship, which provides grants for scholarly work on Objectivism in academia.