Aztec religion

[2] The most important deities were worshiped by priests in Tenochtitlan, particularly Tlaloc and the god of the Mexica, Huitzilopochtli, whose shrines were located on Templo Mayor.

Nahua metaphysics centers around teotl, "a single, dynamic, vivifying, eternally self-generating and self-regenerating sacred power, energy or force.

[12] Priests and educated upper classes held more monistic views, while the popular religion of the uneducated tended to embrace the polytheistic and mythological aspects.

[14] In first contact with the Spanish prior to the conquest, emperor Moctezuma II and the Aztecs generally referred to Cortés and the conquistadors as "teotl".

On the state level, religion was controlled by the Tlatoani and the high priests governing the main temples in the ceremonial precinct of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan.

This level involved the large monthly festivals and a number of specific rituals centered around the ruler dynasty and attempted to stabilize both the political and cosmic systems.

One of these rituals was the feast of Huey Tozoztli, when the ruler himself ascended Mount Tlaloc and engaged in autosacrifice in order to petition the rains.

Under these religious heads were many tiers of priests, priestesses, novices, nuns, and monks (some part-time) who ran the cults of the various gods and goddesses.

Finally, the military orders, professions (e.g. traders (pochteca)) and wards (calpulli) each operated their own lodge dedicated to their specific god.

Duran also describes lodge members as having the responsibility of raising sufficient goods to host the festivals of their specific patron deity.

To maintain the sanctity of the gods, these temple houses were kept fairly dark and mysterious—a characteristic that was further enhanced by having their interiors swirling with smoke from copal (meaning incense) and the burning of offerings.

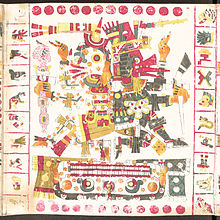

Cortes and Diaz describe these sanctuaries as containing sacred images and relics of the gods, often bejeweled but shrouded under ritual clothes and other veils and hidden behind curtains hung with feathers and bells.

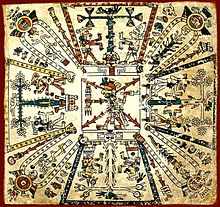

Thus as the sun was believed to dwell in the underworld at night to rise reborn in the morning and maize kernels were interred to later sprout anew, the human and divine existence was also envisioned as being cyclical.

The sky had thirteen layers, the highest of which was called Omeyocan ("place of duality") and served as the residence of the progenitor dual god Ometeotl.

[32] In Aztec cosmology, as in Mesoamerica in general, geographical features such as caves and mountains held symbolic value as places of crossing between the upper and nether worlds.

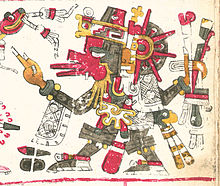

To the Aztecs, death was instrumental in the perpetuation of creation, and gods and humans alike had the responsibility of sacrificing themselves in order to allow life to continue.

Then, by an act of self-sacrifice, one of the gods, Nanahuatzin ("the pimpled one"), caused a fifth and final sun to rise where the first humans, made out of maize dough, could live thanks to his sacrifice.

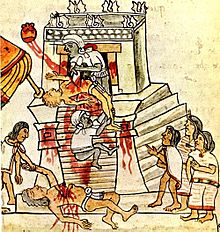

Sacrificial rituals among the Aztecs, and in Mesoamerica in general, must be seen in the context of religious cosmology: sacrifice and death was necessary for the continued existence of the world.

[34] These reenactments often took a form similar to European theater, but the Aztec understanding of such performances were very different; there was no clear divide between the "actor" and the figure they played.

[37] Miguel León-Portilla examines pantheism though he hesitates to label it as entirely pantheistic, instead positing that a specific interpretation of their theology and philosophy is more representative of Aztec thought.

Miguel León-Portilla describes the linguistic evidence for this, found in a passage of the Códice Matritense de la Real Academia and presented in his book Aztec Thought and Culture.

The greatest festival was the xiuhmolpilli, or New Fire ceremony, held every 52 years when the ritual and agricultural calendars coincided and a new cycle started.

Given that such a relation existed, and that ritual functioned to reinforce it, scholars speculate that an unknown method must have been used to maintain the calendar in harmony with the solar year.

Human sacrifice was practiced on a grand scale throughout the Aztec empire, which was performed in honor of the gods,[43] although the exact figures were unknown.

Representations of Huitzilopochtli called teixiptla were also worshipped, the most significant being the one at the Templo Mayor which was made of dough mixed with sacrificial blood.

During the festival priests would march to the top of the volcano Huixachtlan and when the constellation "the fire drill" (Orion's belt) rose over the mountain, a man would be sacrificed.

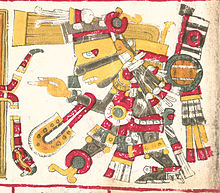

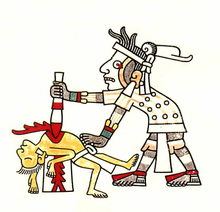

[55] Xipe Totec was worshipped extensively during the festival of Tlacaxipehualiztli, in which captured warriors and slaves were sacrificed in the ceremonial center of the city of Tenochtitlan.

For forty days prior to their sacrifice one victim would be chosen from each ward of the city to act as teixiptla, dress and live as Xipe Totec.

Prior to death and dismemberment the victim's skin would be removed and worn by individuals who traveled throughout the city fighting battles and collecting gifts from the citizens.

Through fear, threat of capital punishment, and boarding schools for young Aztecs, the Spanish tried to enforce worship of the Christian God.