Backward induction

Backward induction is the process of determining a sequence of optimal choices by reasoning from the endpoint of a problem or situation back to its beginning using individual events or actions.

Backward induction was first utilized in 1875 by Arthur Cayley, who discovered the method while attempting to solve the secretary problem.

[2] In dynamic programming, a method of mathematical optimization, backward induction is used for solving the Bellman equation.

[5] The difference is that optimization problems involve one decision maker who chooses what to do at each point of time.

[6][7] Consider a person evaluating potential employment opportunities for the next ten years, denoted as times

In economic terms, this is a scenario with an implicit interest rate of zero and a constant marginal utility of money.

By continuing to work backwards, it can be verified that a 'bad' offer should only be accepted if the person is still unemployed at

Generalizing this example intuitively, it corresponds to the principle that if one expects to work in a job for a long time, it is worth picking carefully.

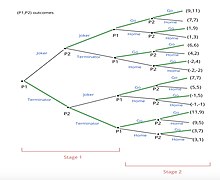

It develops the implications of rationality via individual information sets in the extensive-form representation of a game.

The ultimatum game does have several other Nash Equilibria which are not subgame perfect and therefore do not arise via backward induction.

The pressure or presence of other players and external implications can mean that the game's formal model cannot necessarily predict what a real person will choose.

According to Colin Camerer, an American behavioral economist, Player 2 "rejects offers of less than 20 percent of X about half the time, even though they end up with nothing.

"[12] While backward induction assuming formal rationality would predict that a responder would accept any offer greater than zero, responders in reality are not formally rational players and therefore often seem to care more about offer 'fairness' or perhaps other anticipations of indirect or external effects rather than immediate potential monetary gains.

It will fight by lowering its price, running the entrant out of business (and incurring exit costs—a negative payoff) and damaging its own profits.

However, were the entrant to deviate and enter, the incumbent's best response is to accommodate—the threat of fighting is not credible.

Thus, these strategy profiles that depict subgame perfect equilibria exclude the possibility of actions like incredible threats that are used to "scare off" an entrant.

In this case, backwards induction yielding perfect subgame equilibria ensures that the entrant will not be convinced of the incumbent's threat knowing that it was not a best response in the strategy profile.

Backward induction works only if both players are rational, i.e., always select an action that maximizes their payoff.

Theoretically, this occurs when one or more players have limited foresight and cannot perform backward induction through all terminal nodes.

This deviation occurs as a result of bounded rationality, where players can only perfectly see a few stages ahead.

[16] This allows for unpredictability in decisions and inefficiency in finding and achieving subgame perfect Nash equilibria.

There are three broad hypotheses for this phenomenon: Violations of backward induction is predominantly attributed to the presence of social factors.

Limited backward induction also influences how regularly free-riding occurs within a team's public goods game.

In the game, players would sequentially choose integers inside a range and sum their choices until a target number is reached.

[19] Most tests of backward induction are based on experiments, in which participants are only to a small extent incentivized to perform the task well, if at all.

A large-scale analysis of the American television game show The Price Is Right, for example, provides evidence of limited foresight.

In every episode, contestants play the Showcase Showdown, a sequential game of perfect information for which the optimal strategy can be found through backward induction.

The frequent and systematic deviations from optimal behavior suggest that a sizable proportion of the contestants fail to properly backward induct and myopically consider the next stage of the game only.