Balkh

The Italian explorer and writer Marco Polo described Balkh as "a noble city and a great seat of learning" prior to the Mongol conquests.

[6] Most of the town now consists of ruined buildings, situated some 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) from the right bank of the seasonally flowing Balkh River, at an elevation of about 365 metres (1,198 ft).

The Belgian-French explorer and spiritualist Alexandra David-Néel associated Balkh with Shambhala, a mythical kingdom that features prominently in ancient Tibetan Buddhism, and also offered the Persian Sham-i-Bala (lit.

From this came the intermediate form Bāxli, Sanskrit Bahlīka (also Balhika) for "Bactrian", and by transposition the modern Persian Balx, i.e. Balkh, and Armenian Bahl.

[17] Balkh was earlier considered to be the first city to which the ancient Iranic peoples moved from north of the Amu Darya (also known as the Oxus in Greek), between 2000 and 1500 BC.

[18] However it was only recently that archaeological remains before 500 BC were found by French archaeologists led by Johanna Lhullier and Julio Bendezu-Sarmiento in the section called Bala Hissar, which is the citadel of the site.

[20] Another mound of the site, known as Tepe Zargaran, and the Northern Fortification Wall of Balkh, were occupied at a large extension in Achaemenid times (Yaz III period, c. 540-330 BC).

Its foundation is mythically ascribed to Keyumars, the first king of the world in Persian legend; and it is at least certain that, at a very early date, it was the rival of Ecbatana, Nineveh and Babylon.

[15] For a long time the city and country was the central seat of the dualistic Zoroastrian religion, the founder of which, Zoroaster, died within the walls according to the Persian poet Firdowsi.

Alexander the Great married Roxana of Bactria after killing the king of Balkh in the 4th century BC, and brought the Greek culture and religion to the region.

[24] During the 8th century, the Korean monk and traveler Hyecho (704–787 CE) recorded that even after the Arab invasion, the residents of Balkh continued to practice Buddhism and followed a Buddhist king.

[citation needed] A curious reference to this building is found in the writings of the geographer Ibn Hawqal, an Arab traveler of the 10th century, who describes Balkh as built of clay, with ramparts and six gates, and extending for half a parasang.

A large number of Sanskrit medical, pharmacological, and toxicological texts were translated into Arabic under the patronage of Khalid, the vizier of Al-Mansur.

[27] Sennacherib, who reigned over the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705 to 681 BCE, is said to have forcibly transferred some Israelites to Balkh after dispossessing them from the Kingdom of Israel during the Assyrian captivity.

This account is discussed in the works of the Egyptian historian Al-Maqrizi, who wrote that the arrival and establishment of the Jews in Balkh had occurred in light of Sennacherib's campaign in the Levant.

[29] Balkh's Jewish community was further noted in the Ghaznavid Empire during the 11th century, when Jews were forced to maintain a garden for Mahmud of Ghazni and pay a minority tax of 500 dirhams.

"[31][32] Hiwi al-Balkhi, a 9th-century exegete and Bible critic, was born in Balkh and is widely believed to have been a Bukharan Jew, at least by ethnicity, as some scholars have asserted that he was a practicing gnostic Christian.

At the time of the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century, however, Balkh had provided an outpost of resistance and a safe haven for the Persian emperor Yazdegerd III who fled there from the armies of Umar.

Later, in the 9th century, during the reign of Ya'qub bin Laith as-Saffar, Islam became firmly rooted in the local population.Arabs occupied Persia in 642 (during the Caliphate of Uthman, 644–656 AD).

It is said that they raided the famous Buddhist shrine of Nava-Vihara, which the Arab historians call 'Nava Bahara' and describe it as one of the magnificent places, which comprised a range of 360 cells around the high stupas'.

They plundered the gems and jewels that were studded on many images and stupas and took away the wealth accumulated in the Vihara but probably did no considerable harm to other monastic buildings or to the monks residing there".

The Arabs' control over Balkh did not last long as it soon came under the rule of a local prince, a zealous Buddhist called Nazak (or Nizak) Tarkhan.

[33] In 726, the Umayyad governor Asad ibn Abdallah al-Qasri rebuilt Balkh and installed in it an Arab garrison,[34] while in his second governorship, a decade later, he transferred the provincial capital there.

Ahmad Sanjar decisively defeated a Ghurid army, commanded by Ala al-Din Husayn and he took him prisoner for two years before releasing him as a vassal of the Seljuks.

[36] In 1220 Genghis Khan sacked Balkh, butchered its inhabitants and levelled all the buildings capable of defence – treatment to which it was again subjected in the 14th century by Timur.

For when Ibn Battuta visited Balkh around 1333 during the rule of the Kartids, who were Tadjik vassals of the Persia-based Mongol Ilkhanate until 1335, he described it as a city still in ruins: "It is completely dilapidated and uninhabited, but anyone seeing it would think it to be inhabited because of the solidity of its construction (for it was a vast and important city), and its mosques and colleges preserve their outward appearance even now, with the inscriptions on their buildings incised with lapis-blue paints.

The area of Balkh was governed by the Uzbek Qataghan dynasty, with its capital in Khulm, for the majority of the early nineteenth century, and only nominally acknowledged Kabul's suzerainty.

[42][43] In 1911 Balkh comprised a settlement of about 500 houses of Afghan settlers, a colony of Jews and a small bazaar set in the midst of a waste of ruins and acres of debris.

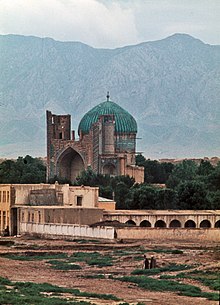

The Green Mosque (Persian: مَسجد سَبز, romanized: Masjid Sabz),[45] named for its green-tiled dome (see photograph top right corner) and said to be the tomb of the Khwaja Abu Nasr Parsa, had nothing but the arched entrance remaining of the former madrasah (Arabic: مَـدْرَسَـة, school).

Modern Balkh is a centre of the cotton industry, of the skins known commonly in the West as "Persian lamb" (Karakul), and for agricultural produce like almonds and melons.