Baker Street and Waterloo Railway

In 1900, work was hit by the financial collapse of its parent company, the London & Globe Finance Corporation, through the fraud of Whitaker Wright, its main shareholder.

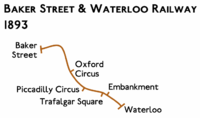

Carriages would have been sucked or blown a distance of three-quarters of a mile (about 1 km) from Great Scotland Yard to Waterloo Station, travelling through wrought-iron tubes laid in a trench at the bottom of the Thames.

[4] According to a pamphlet published by the BS&WR in 1906, the idea of constructing the line "originally arose from the desire of a few business men in Westminster to get to and from Lord's Cricket Ground as quickly as possible," to enable them to see the last hour's play without having to leave their offices too early.

They realised that an underground railway line connecting the north and south of central London would provide "a long-felt want of transport facilities" and "would therefore prove a great financial success."

[7] Bills for three similarly inspired new underground railways were also submitted to Parliament for the 1892 parliamentary session, and, to ensure a consistent approach, a Joint Select Committee was established to review the proposals.

The committee took evidence on various matters regarding the construction and operation of deep-tube railways, and made recommendations on the diameter of tube tunnels, method of traction, and the granting of wayleaves.

After rejecting the construction of stations on land owned by the Crown Estate and the Duke of Portland between Oxford Circus and Baker Street, the Committee allowed the BS&WR bill to proceed for normal parliamentary consideration.

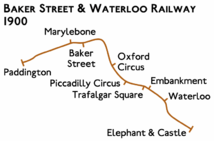

In its prospectus of November 1900, the company forecast that it would realise £260,000 a year from passenger traffic, with working expenses of £100,000, leaving £138,240 for dividends after the deduction of interest payments.

[20] The BS&WR struggled on for a time, funding the construction work by making calls on the unpaid portion of its shares,[16] but activity eventually came to a stop and the partly built tunnels were left derelict.

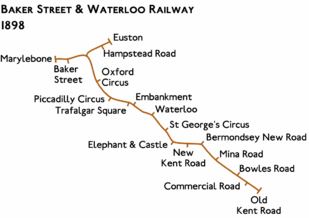

The bill for 1899, published on 22 November 1898, requested more time for the construction works and proposed two extensions to the railway and a modification to part of the previously approved route.

The single tunnel was then to turn north-east, passing under the Regent's Canal to the east of Little Venice, before coming to the surface where a depot was to be built on the north side of Blomfield Road.

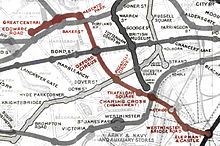

[26] The aim of these plans was, as the company put it in 1906, "to tap the large traffic of the South London Tramways, and to link up by a direct Line several of the most important Railway termini.

c. cxcii) received royal assent on 1 August 1899, only the extension of time and the route change at Waterloo were approved[26][30] In November 1899, the BS&WR announced a bill for the 1900 session.

[36] The merger was rejected by Parliament,[37] but the land purchase and extension of time were permitted separately in the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway Act 1903 (3 Edw.

[4] The main construction site was located at a substantial temporary staging pier erected in the River Thames a short distance south of the Hungerford Bridge.

[41] It was described at the time as "a small village of workshops and offices and an electrical generating station to provide the power for driving the machinery and for lighting purposes during construction.

It was originally intended that the work should begin close to the south bank, with a bridge connecting the stage to College Street – a now-vanished road on the site of the present-day Jubilee Gardens.

However, test borings showed that there was a deep depression in the gravel beneath the Thames, which it was speculated was the result of dredging carried out for the abortive Charing Cross & Waterloo Railway project.

[56] To reduce the risk of fire, the station platforms were built of concrete and iron and the sleepers were made from the fireproof Australian wood Eucalyptus marginata or jarrah.

[69] To add to the line's misfortunes, it suffered its first fatality only two weeks after opening when conductor John Creagh was crushed between a train and a tunnel wall at Kennington Road station on 26 March.

[71] The Daily Mirror noted at the end of April 1906 that the BS&WR offered poor value for money compared to the equivalent motor bus service, which cost only 1d.

There was duplicated administration between the three companies and, to streamline the management and reduce expenditure, the UERL announced a bill in November 1909 that would merge the Bakerloo, the Hampstead and the Piccadilly Tubes into a single entity, the London Electric Railway (LER), although the lines retained their own individual branding.

[76] In a pamphlet published in 1906 to publicise the Paddington extension, the company proclaimed: [I]t will thus be seen that the advantages which this line will afford for getting quickly and cheaply from one point of London to another are without parallel.

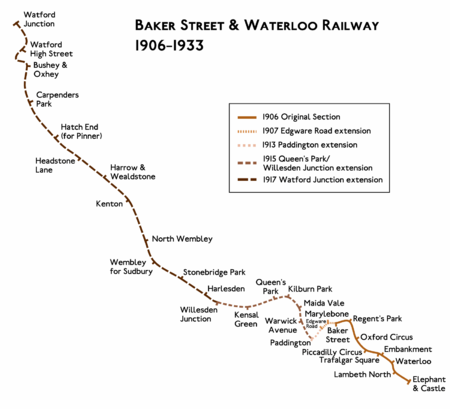

[83] The new route ran 890 metres (2,920 ft) in a tight curve from Edgware Road station, initially heading south before turning to the north-west, which provided a more practical direction for a future extension.

[90] The extension was to continue north from Paddington, running past Little Venice to Maida Vale before curving north-west to Kilburn and then west to parallel the LNWR main line, before coming to the surface a short distance to the east of Queen's Park station.

Maida Vale and Kilburn Park were provided with buildings in the style of the earlier Leslie Green stations but without the upper storey, which was no longer required for housing lift gear.

In 1913, the Lord Mayor of London announced a proposal for the Bakerloo Tube to be extended to the Crystal Palace via Camberwell Green, Dulwich and Sydenham Hill, but nothing was done to implement the plan.

A large circular ticket hall was excavated below the road junction with multiple subway connections from points around the Circus and two flights of escalators down to the Bakerloo and Piccadilly platforms were installed.

Ashfield aimed for regulation that would give the UERL group protection from competition and allow it to take substantive control of the LCC's tram system; Morrison preferred full public ownership.

[106] Rising construction costs caused by difficult ground conditions and restricted funds in the post-war austerity period led the scheme to be cancelled again in 1950.