Kongo people

[8] The Kongo people were among the earliest indigenous Africans to welcome Portuguese traders in 1483 CE, and began converting to Catholicism in the late 15th century.

[7] The slave raids, colonial wars and the 19th-century Scramble for Africa split the Kongo people into Portuguese, Belgian and French parts.

[11] According to the colonial era scholar Samuel Nelson, the term Kongo is possibly derived from a local verb for gathering or assembly.

[11] Christian missionaries, particularly in the Caribbean, originally applied the term Bafiote (singular M(a)fiote) to the slaves from the Vili or Fiote coastal Kongo people, but later this term was used to refer to any "black man" in Cuba, St Lucia and other colonial era Islands ruled by one of the European colonial interests.

[16] Since the early 20th century, Bakongo (singular Mkongo or Mukongo) has been increasingly used, especially in areas north of the Congo River, to refer to the Kikongo-speaking community, or more broadly to speakers of the closely related Kongo languages.

This geographical proximity, states Jan Vansina, suggests that the Congo River region, home of the Kongo people, was populated thousands of years ago.

[19] The Kongo people had settled into the area well before the fifth century CE, begun a society that utilized the diverse and rich resources of region and developed farming methods.

Detailed and copious description about the Kongo people who lived next to the Atlantic ports of the region, as a sophisticated culture, language and infrastructure, appear in the 15th century, written by the Portuguese explorers.

The evidence suggests, states Vansina, that the Kongo people were advanced in their culture and socio-political systems with multiple kingdoms well before the arrival of first Portuguese ships in the late 15th century.

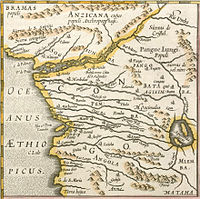

[25] The Portuguese arrived on the Central African coast north of the Congo River, several times between 1472 and 1483 searching for a sea route to India,[25] but they failed to find any ports or trading opportunities.

The kingdom of Kongo appeared to become receptive of the new traders, allowed them to settle an uninhabited nearby island called São Tomé, and sent Bakongo nobles to visit the royal court in Portugal.

Soon thereafter they began kidnapping people from the Kongo society and after 1514, they provoked military campaigns in nearby African regions to get slave labor.

[26] The Portuguese operators approached the traders at the borders of the Kongo kingdom, such as the Malebo Pool and offered luxury goods in exchange for captured slaves.

This created, states Jan Vansina, an incentive for border conflicts and slave caravan routes, from other ethnic groups and different parts of Africa, in which the Kongo people and traders participated.

[30][32] There are other scholars, such as Joseph Miller, that believed this 16th and 17th centuries' one-sided dehumanization of the African people was a fabrication and myth created by the missionaries and slave trading Portuguese to hide their abusive activities and intentions.

The weakened Kingdom of Kongo continued to face internal revolts and violence that resulted from the raids and capture of slaves, and the Portuguese in 1575 established the port city of Luanda (now in Angola) in cooperation with a Kongo noble family to facilitate their military presence, African operations and the slave trade thereof.

[38] The fragmented new kingdoms of the Kongo people disputed each other's boundaries and rights, as well as those of other non-Kongo ethnic groups bordering them, leading to steady wars and mutual raids.

[40][41] In the 1700s, a baptized teenage Kongo woman named Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita claimed to be possessed by Saint Anthony of Padua and that she had been visiting heaven to speak with God.

[7] The conflicts continued through the 18th century, however, and the demand for and the caravan of Kongo and non-Kongo people as captured slaves kept rising, headed to the Atlantic ports.

There were succession crises, ensuing conflicts when a local royal Kongo ruler died and occasional coups such as that of Andre II by Henrique III, typically settled with Portuguese intervention, and these continued through the mid 19th-century.

One of them, Pedro Elelo, gained the trust of Portuguese military against Alvero XIII, by agreeing to be vassal of the colonial Portugal.

[45] In concert with the growing import of Christian missionaries and luxury goods, the slave capture and exports through the Kongo lands grew.

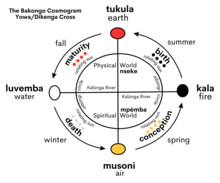

Then Nzambi Mpungu, the creator god, summoned a great force of fire, called Kalûnga, which filled this empty circle.

The last period of time is luvemba, when a muntu physically dies and enters the spiritual world, or Nu Mpémba, with of the ancestors, or bakulu.

According to historian John K. Thornton, "Central Africans have probably never agreed among themselves as to what their cosmology is in detail, a product of what I called the process of continuous revelation and precarious priesthood.

"[62] The Kongo people had diverse views, with traditional religious ideas best developed in the small northern Kikongo-speaking area, and this region neither converted to Christianity nor participated in slave trade until the 19th century.

[62] There is abundant description about Kongo religious concepts in the Catholic missionary and colonial era records, but states Thornton, these are written with a hostile bias and their reliability is problematic.

[62] These deities were guardians of water bodies, crop lands and high places to the Kongo people, and they were very prevalent both in capital towns of the Christian ruling classes, as well as in the villages.

[5] This may be linked to the premises of dualistic cosmology in Bakongo tradition, where two worlds exist, one visible and lived, another invisible and full of powerful spirits.

The Haplogroup L2a is a mtdna clade that was found to be common in the Democratic Republic of Congo amongst Bantu groups, including the Bakongo.