Balfour Declaration

The declaration was contained in a letter dated 2 November 1917 from the United Kingdom's Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to Lord Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland.

By late 1917, in the lead-up to the Balfour Declaration, the wider war had reached a stalemate, with two of Britain's allies not fully engaged: the United States had yet to suffer a casualty, and the Russians were in the midst of a revolution with Bolsheviks taking over the government.

[14][15] The 1881–1884 anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire encouraged the growth of the latter identity, resulting in the formation of the Hovevei Zion pioneer organizations, the publication of Leon Pinsker's Autoemancipation, and the first major wave of Jewish immigration to Palestine – retrospectively named the "First Aliyah".

[vi] Earlier that year, Balfour had successfully driven the Aliens Act through Parliament with impassioned speeches regarding the need to restrict the wave of immigration into Britain from Jews fleeing the Russian Empire.

[30] This connection was to bear fruit later that year when the Baron's son, James de Rothschild, requested a meeting with Weizmann on 25 November 1914, to enlist him in influencing those deemed to be receptive within the British government to the Zionist agenda in Palestine.

[c][32] Through James's wife Dorothy, Weizmann was to meet Rózsika Rothschild, who introduced him to the English branch of the family – in particular her husband Charles and his older brother Walter, a zoologist and former Member of Parliament (MP).

[50] The Chancellor, whose law firm Lloyd George, Roberts and Co had been engaged a decade before by the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland to work on the Uganda Scheme,[51] was to become Prime Minister by the time of the declaration, and was ultimately responsible for it.

[76][77] Sykes was a British Conservative MP who had risen to a position of significant influence on Britain's Middle East policy, beginning with his seat on the 1915 De Bunsen Committee and his initiative to create the Arab Bureau.

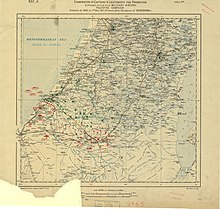

[78] Their agreement defined the proposed spheres of influence and control in Western Asia should the Triple Entente succeed in defeating the Ottoman Empire during World War I,[79][80] dividing many Arab territories into British- and French-administered areas.

The Jewish population will be secured in the enjoyment of civil and religious liberty, equal political rights with the rest of the population, reasonable facilities for immigration and colonisation, and such municipal privileges in the towns and colonies inhabited by them as may be shown to be necessary.On 11 March, telegrams[l] were sent in Grey's name to Britain's Russian and French ambassadors for transmission to Russian and French authorities, including the formula, as well as: The scheme might be made far more attractive to the majority of Jews if it held out to them the prospect that when in course of time the Jewish colonists in Palestine grow strong enough to cope with the Arab population they may be allowed to take the management of the internal affairs of Palestine (with the exception of Jerusalem and the holy places) into their own hands.Sykes, having seen the telegram, had discussions with Picot and proposed (making reference to Samuel's memorandum[m]) the creation of an Arab Sultanate under French and British protection, some means of administering the holy places along with the establishment of a company to purchase land for Jewish colonists, who would then become citizens with equal rights to Arabs.

"[95] Subsequent pressure from Lloyd George, over the reservations of Robertson, resulted in the recapture of the Sinai for British-controlled Egypt, and, with the capture of El Arish in December 1916 and Rafah in January 1917, the arrival of British forces at the southern borders of the Ottoman Empire.

[y] A month later, Curzon produced a memorandum[167] circulated on 26 October 1917 where he addressed two questions, the first concerning the meaning of the phrase "a National Home for the Jewish race in Palestine"; he noted that there were different opinions ranging from a fully fledged state to a merely spiritual centre for the Jews.

[172] Historian Matthew Jacobs later wrote that the US approach was hampered by the "general absence of specialist knowledge about the region" and that "like much of the Inquiry's work on the Middle East, the reports on Palestine were deeply flawed" and "presupposed a particular outcome of the conflict".

"[171] Yair Auron opines that Cecil, then a deputy Foreign Secretary representing the British Government at a celebratory gathering of the English Zionist Federation, "possibly went beyond his official brief" in saying (he cites Stein) "Our wish is that Arabian countries shall be for the Arabs, Armenia for the Armenians and Judaea for the Jews".

"[xxii][xxiii] Emir Faisal, King of Syria and Iraq, made a formal written agreement with Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann, which was drafted by T. E. Lawrence, whereby they would try to establish a peaceful relationship between Arabs and Jews in Palestine.

[aa] In a subsequent letter written in English by Lawrence for Faisal's signature, he explained: We feel that the Arabs and Jews are cousins in race, suffering similar oppression at the hands of powers stronger than themselves, and by a happy coincidence have been able to take the first step toward the attainment of their national ideals together.

[251] Shortly after beginning the role in July 1920, he was invited to read the haftarah from Isaiah 40 at the Hurva Synagogue in Jerusalem,[252] which, according to his memoirs, led the congregation of older settlers to feel that the "fulfilment of ancient prophecy might at last be at hand".

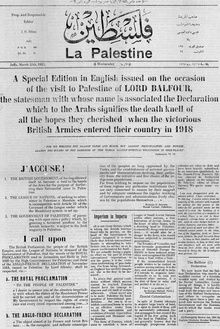

[257] They handed a petition signed by more than 100 notables to Ronald Storrs, the British military governor: We have noticed yesterday a large crowd of Jews carrying banners and over-running the streets shouting words which hurt the feeling and wound the soul.

[90] Following the publication of the declaration in an Egyptian newspaper, Al Muqattam,[262] the British dispatched Commander David George Hogarth to see Hussein in January 1918 bearing the message that the "political and economic freedom" of the Palestinian population was not in question.

In March 1924, having briefly considered the possibility of removing the offending article from the treaty, the government suspended any further negotiations;[269] within six months they withdrew their support in favour of their central Arabian ally Ibn Saud, who proceeded to conquer Hussein's kingdom.

[278] The Italian endorsement of the Declaration had included the condition "... on the understanding that there is no prejudice against the legal and political status of the already existing religious communities ..."[280] The boundaries of Palestine were left unspecified, to "be determined by the Principal Allied Powers.

[286] Professor Lawrence Davidson, of West Chester University, whose research focuses on American relations with the Middle East, argues that President Wilson and Congress ignored democratic values in favour of "biblical romanticism" when they endorsed the declaration.

[289][ao] Two weeks following the declaration, Ottokar Czernin, the Austrian Foreign Minister, gave an interview to Arthur Hantke, President of the Zionist Federation of Germany, promising that his government would influence the Turks once the war was over.

[ar] I do not attach undue importance to this movement, but it is increasingly difficult to meet the argument that it is unfair to ask the British taxpayer, already overwhelmed with taxation, to bear the cost of imposing on Palestine an unpopular policy.

[as] Two years later, in his Memoirs of the Peace Conference,[at] Lloyd George described a total of nine factors motivating his decision as Prime Minister to release the declaration,[156] including the additional reasons that a Jewish presence in Palestine would strengthen Britain's position on the Suez Canal and reinforce the route to their imperial dominion in India.

[xxxiii] Some historians argue that the British government's decision reflected what James Gelvin, Professor of Middle Eastern History at UCLA, calls 'patrician anti-Semitism' in the overestimation of Jewish power in both the United States and Russia.

[336] Shlaim states that Stein does not reach any clear cut conclusions, but that implicit in his narrative is that the declaration resulted primarily from the activity and skill of the Zionists, whereas according to Vereté, it was the work of hard-headed pragmatists motivated by British imperial interests in the Middle East.

[337] Danny Gutwein, Professor of Jewish History at the University of Haifa, proposes a twist on an old idea, asserting that Sykes's February 1917 approach to the Zionists was the defining moment, and that it was consistent with the pursuit of the government's wider agenda to partition the Ottoman Empire.

[xxxvi] Historian J. C. Hurewitz has written that British support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine was part of an effort to secure a land bridge between Egypt and the Persian Gulf by annexing territory from the Ottoman Empire.

[au] The Palestine Royal Commission – in making the first official proposal for partition of the region – referred to the requirements as "contradictory obligations",[353][354] and that the "disease is so deep-rooted that, in our firm conviction, the only hope of a cure lies in a surgical operation".