Ballista

Developed from earlier Greek weapons, it relied upon different mechanics, using two levers with torsion springs instead of a tension prod (the bow part of a modern crossbow).

By contrast, the comparatively slow relaxation time of the bow or prod of a conventional crossbow such as the oxybeles meant that much less energy could be transferred to light projectiles, limiting the effective range of the weapon.

For all of the tactical advantages offered, it was only under Philip II of Macedon, and even more so under his son Alexander, that the ballista began to develop and gain recognition as both a siege engine and field artillery.

Historical accounts, for instance, cited that Philip II employed a group of engineers within his army to design and build catapults for his military campaigns.

[6] It was further perfected by Alexander, whose own team of engineers introduced innovations such as the idea of using springs made from tightly strung coils of rope instead of a bow to achieve more energy and power when throwing projectiles.

Ballistae could be easily modified to shoot both spherical and shaft projectiles, allowing their crews to adapt quickly to prevailing battlefield situations in real time.

This included the great military machine advances the Greeks had made (most notably by Dionysus of Syracuse), as well as all the scientific, mathematical, political and artistic developments.

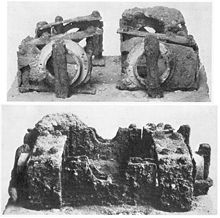

The slider passed through the field frames of the weapon, in which were located the torsion springs (rope made of animal sinew), which were twisted around the bow arms, which in turn, were attached to the bowstring.

The bronze or iron caps, which secured the torsion bundles were adjustable by means of pins and peripheral holes, which allowed the weapon to be tuned for symmetrical power and for changing weather conditions.

The ballista was a highly accurate weapon (there are many accounts of single soldiers being picked off by ballistarii), but some design aspects meant it could compromise its accuracy for range.

Seeing this, Caesar ordered the warships – which were swifter and easier to handle than the transports, and likely to impress the natives more by their unfamiliar appearance – to be removed a short distance from the others, and then be rowed hard and run ashore on the enemy’s right flank, from which position men on deck could use the slings, bows, and artillery to drive them back.

"[8] Ballistae were not only used in laying siege: after AD 350, at least 22 semi-circular towers were erected around the walls of Londinium (London) to provide platforms for permanently mounted defensive devices.

So when men wish to shoot at the enemy with this, they make the parts of the bow which form the ends bend toward one another by means of a short rope fastened to them, and they place in the grooved shaft the arrow, which is about one half the length of the ordinary missiles which they shoot from bows, but about four times as wide...but the missile is discharged from the shaft, and with such force that it attains the distance of not less than two bow-shots, and that, when it hits a tree or a rock, it pierces it easily.

Such is the engine which bears this name, being so called because it shoots with very great force...[10]The missiles were able to penetrate body-armour: And at the Salarian Gate a Goth of goodly stature and a capable warrior, wearing a corselet and having a helmet on his head, a man who was of no mean station in the Gothic nation, refused to remain in the ranks with his comrades, but stood by a tree and kept shooting many missiles at the parapet.

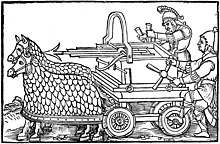

The cart system and structure gave it a great deal of flexibility and capability as a battlefield weapon, since the increased maneuverability allowed it to be moved with the flow of the battle.

Reconstruction and trials of such a weapon carried out in a BBC documentary, What the Romans Did For Us, showed that they "were able to shoot eleven bolts a minute, which is almost four times the rate at which an ordinary ballista can be operated".

Although several ancient authors (such as Vegetius) wrote very detailed technical treatises, providing us with all the information necessary to reconstruct the weapons, all their measurements were in their native language and therefore highly difficult to translate.

[citation needed] The most influential archaeologists in this area have been Peter Connolly and Eric Marsden,[13] who have not only written extensively on the subject but have also made many reconstructions themselves and have refined the designs over many years of work.

With the decline of the Roman Empire, resources to build and maintain these complex machines became very scarce, so the ballista was likely supplanted initially by the simpler and cheaper onager and the more efficient springald.