Baltimore railroad strike of 1877

It formed a part of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, during which widespread civil unrest spread nationwide following the global depression and economic downturns of the mid-1870s.

Violence erupted in Baltimore on July 20, with police and soldiers of the Maryland National Guard clashing with crowds of thousands gathered throughout the city.

In response, President Rutherford B. Hayes ordered federal troops to Baltimore, local officials recruited 500 additional police, and two new national guard regiments were formed.

Violence began in Martinsburg, West Virginia and spread along the rail lines through Baltimore and on to several major cities and transportation hubs of the time, including Reading, Scranton and Shamokin, Pennsylvania; a bloodless general strike in St. Louis, Missouri; and a short lived uprising in Chicago, Illinois.

What began as the peaceful actions of organized labor attracted the masses of discontented and unemployed workers spawned by the depression, along with others who took opportunistic advantage of the chaos.

[15]: 17–8 The number of unemployed along the line was so great, owing to the ongoing economic problems, that the company had no difficulty replacing the absent strikers.

In response, the strikers resolved to occupy portions of the rail line, and to stop trains from passing unless the company rescinded the wage cuts.

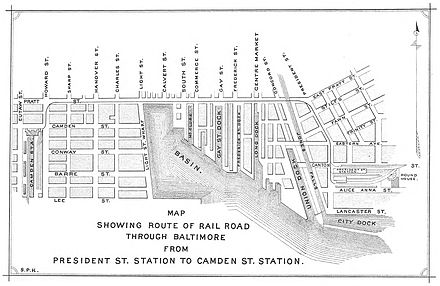

[15]: 18 On July 16, the day the reduction was to go into effect, about 40 men gathered at Camden Junction, 3 miles (4.8 km) from Baltimore, and stopped traffic.

[15]: 19 Newspapers reported a meeting held by rail workers who were sympathetic to the strike, which by that day included brakemen and engineers as well as firemen.

[16] That same day in Baltimore, hundreds of manufacturing workers declared a strike,[1]: 138 [5]: 30 and the box-makers and sawyers walked out, demanding a ten percent increase in wages.

[16] That day, The Sun reported the situation in the city: One by one the shops have become wholly or partly silent, and very many men, especially in South Baltimore, are without work or the means of providing for their families.

[5]: 53–5 A committee representing the strikers (including engineers, conductors, firemen, and brakemen) departed Baltimore to ensure solidarity along the line in demanding $2 per day.

[5]: 62–3 At 4:00 pm Brigadier General James R. Herbert was ordered by Governor Carroll to muster the troops of the 5th and 6th Regiments, Maryland National Guard, to their respective armories in preparation.

[1]: 138 [19] With the knowledge that groups of workers had been dispersed along the lines to impede traffic, including the movement of troops, he issued a simultaneous declaration to the people of the state: I ... by virtue of the authority vested in me, do hereby issue this my proclamation, calling upon all citizens of this State to abstain from acts of lawlessness, and aid lawful authorities in the maintenance of peace and order.

[3]: 98 [7]: 735 Their armory, located on Front Street across from the Phoenix Shot Tower, consisted of the second and third floors of a warehouse, with the only exit being a narrow stairway through which no more than two men could walk abreast.

[15]: 57 [19] Shortly after 8:00 pm, Colonel Peters ordered three companies of 120 men of the 6th to move as commanded by the governor and General Herbert to Camden Station.

[15]: 59–60 [19] As reported by The Sun, Governor Carroll and Mayor Latrobe were present at the station, along with B&O vice president King, General Herbert and his staff, and a number of police commissioners.

[15]: 60 Some firefighters dispatched to the scene were driven off, and others had their hoses cut when they attempted to set up their pumps, but, under the protection of the police and soldiers, the flames were extinguished.

[3]: 96 The bars in Baltimore remained closed, and a guard of soldiers and police protected workers as they set about the task of repairing the tracks and restoring the station to operating order.

[15]: 65 President Hayes released a proclamation in which he admonished: all good citizens ... against aiding, countenancing, abetting or taking part in such unlawful proceedings, and I do hereby warn all persons engaged in or connected with said domestic violence and obstruction of the laws to disperse and retire peaceably to their respective abodes on or before twelve o'clock noon of the 22d day of July[15]: 64–5 After dark, a mob of 2,500–3,000 gathered at Camden Station, jeering the soldiers.

[3]: 102 On Eutaw Street, where the sentinels had remained, the men fixed bayonets, and briefly struggled with the crowd as they attempted and failed to break the line.

[7]: 739 The news reported that 16 were arrested in a confrontation between citizens and the police at Lee and Eutaw,[6] and that during the night, three separate attempts were made to set fire the 6th Regiment armory, but all were frustrated by the remaining garrison there.

[3]: 103 [8] At 4:00 am another alarm sounded: the planing mills and lumber yard of J. Turner & Cate near the Philadelphia Wilmington & Baltimore rail depot, had been set on fire.

[8] Around 10:00 am, General W. S. Hancock arrived and was followed by 360–400 federal troops from New York and Fort Monroe, who relieved those guarding Camden Station.

[24] On Thursday, July 26, a committee from the engineers, firemen, brakemen, and conductors met with Governor Carroll, as recounted in the following day's newspapers.

[26] B&O vice president King published a reply to the demands of the strikers, saying that they could not be met for lack of work and low prices for hauling freight.

[26]Later that evening, second vice president Keyser, upon the request of the strikers, addressed a workingmen's meeting at Cross Street Market Hall, and presented the company's written response reprinted in the papers for the public.

The Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser reported a general hope that, owing to the imminent increase in traffic due to the transport of harvested crops, the firemen would be able to make daily round trips, thus avoiding layovers, and that the company could arrange for them to return home on passenger trains when this was not feasible.

[27] Keyser's reprinted response advised that the ten percent cut was "forced upon the company", but that he was confident they would be able to provide more full employment, and thus increase wages, due to an abundance of freight to be moved.

"[26] The force gathered at Camden Station at 8:30 am on Saturday, July 29, included 250 federal troops, 250 men of the 5th Maryland Regiment, and 260 policemen.