Baltringer Haufen

The name derived from the small Upper Swabian village of Baltringen, which lies approximately 25 kilometres (16 mi) south of Ulm in the district of Biberach, Germany.

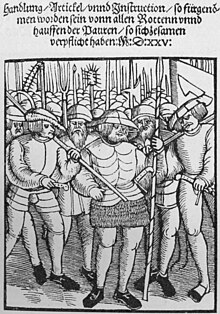

In the early modern period the term Haufe(n) (literally: heap) denoted a lightly organised military formation particularly with regard to Landsknecht regiments.

[1] According to the account of a nun from nearby Heggbach Abbey, local peasants assembled and conferred in an inn at Baltringen for the first time on Christmas Eve 1524.

[5] Soon the authorities learnt of these meetings and representatives of the Swabian League, an association of Imperial cities, principalities, both ecclesiastic and secular, and knights, contacted the Baltringer Haufen.

Ulrich Schmid, the representative of the Baltringer Haufen, rejected the traditional legal process through the Imperial Chamber Court to solve the complaints of the peasants.

[11] Ulrich Schmid hoped that regarding this issue he would be helped in Memmingen[12] where he managed to recruit Sebastian Lotzer, a journeyman furrier, to take on the role of clerk to the Baltringer Haufen.

The wording of this missive seems to imply that there may already have been contacts between Lotzer, who resided in Memmingen and had been active as clerk to the Memminger peasants, and Schmid well before the end of February 1525.

As a consequence, at the beginning of 1525 the troops of the Swabian League commanded by Georg Truchsess von Waldburg (later known as Bauernjörg) were occupied in suppressing an attempt by Duke Ulrich to regain his throne.

[20] During the second half of March 1525 the Swabian League's military action against Duke Ulrich of Württemberg finally ended which freed forces to intervene in Upper Swabia.

The situation escalated after news that troops of the Swabian League, consisting of 8000 footsoldiers and 3000 cavalry,[21] had arrived at Ulm reached the peasants on 26 March 1525.

Even though the commanding officer of this detachment, Count Wilhelm von Fürstenberg, had planned to cross the Danube with all his forces, he did not manage to have his artillery traverse the river and due to the boggy terrain the cavalry could not be utilised either.

Following these first unsuccessful attempts to subdue the Baltringer Haufen, Georg Truchsess von Waldburg then turned to face the challenge of the seemingly more threatening peasant army that had formed near Leipheim.

During the ensuing battle, the Leipheimer Haufen was utterly defeated on 4 April 1525; their leaders, Hans Jakob Wehe and seven others, were executed by being beheaded the next day.

[25] On 10 April 1525 the Swabian League's army under the command of Georg Truchsess von Waldburg departed Leipheim in order to return to Upper Swabia.

In Biberach, for example, the Spital, a charitable institution and at the same time a large landowner in Upper Swabia, imposed fines on 684 of its approximately 2400 subjects in 38 villages.

[33] The leaders of the Baltringer Haufen, Ulrich Schmid, Sebastian Lotzer and Christoph Schappeler, managed to save their lives by escaping to Switzerland.

Even though it was not successful in persuading the other Haufen to follow its demand of non-violence and its invocation of the "Divine Law",[37] its leaders nevertheless suggested the merging of the three dominant peasant armies in the region to form the Christian Alliance.

The influence and contribution of the Baltringer Haufen is clearly visible in the Twelve Articles and the Federal Ordinance both of which became the most important manifestos of the German Peasants' War.

What turned out to be even more important, however, was the lack of military and political leaders who were able to survey and assess the situation as a whole and combine the multitude of local complaints into an effective challenge the Swabian League had to reckon with.