Buddhas of Bamiyan

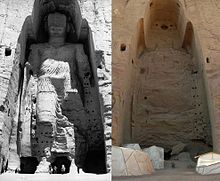

The main bodies were hewn directly from the sandstone cliffs, but details were modeled in mud mixed with straw, coated with stucco.

[13][14] Later in the 17th century, Mughal emperor Aurangzeb briefly ordered the use of artillery to destroy the statues, causing some damage, though the Buddhas survived without any major harm.

The Great Buddhas of Bamiyan were built around 600 CE during the time of the Hephthalites, who ruled as principalities in the areas of Tokharistan and northern Afghanistan.

For instance, during the time of Song Yun, who visited the chief of the Hephthalite nomads at his summer residence in Badakhshan and later in Gandhara, said that they had no belief in the Buddhist law and served a large number of divinities.

[1] Murals in the adjoining caves have been carbon dated from 438 to 980 CE, suggesting that Buddhist artistic activity continued down to the final occupation by the Muslims.

[12][28] A monumental seated Buddha, similar in style to those at Bamyan, still exists in the Bingling Temple caves in China's Gansu province.

[34] The central image of the Sun God on his golden chariot is framed by two lateral rows of individuals: kings and dignitaries mingling with Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

These were mixed with a range of binders, including natural resins, gums (possibly animal skin glue or egg),[46] and oils, probably derived from walnuts or poppies.

[44] Specifically, researchers identified drying oils from murals showing Buddhas in vermilion robes sitting cross-legged amid palm leaves and mythical creatures as being painted in the middle of the 7th century.

[52] In early 2000, local Taliban authorities asked for the UN's assistance to rebuild drainage ditches around the tops of the alcoves where the Buddhas were set.

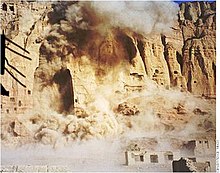

"[54] During a 13 March interview for Japan's Mainichi Shimbun, Afghan Foreign Minister Wakil Ahmad Mutawakel stated that the destruction was anything but a retaliation against the international community for economic sanctions: "We are destroying the statues in accordance with Islamic law and it is purely a religious issue."

I thought, these callous people have no regard for thousands of living human beings—the Afghans who are dying of hunger, but they are so concerned about non-living objects like the Buddha.

[58]There is additional speculation that the destruction may have been influenced by al-Qaeda in order to further isolate the Taliban from the international community, thus tightening relations between the two; however, the evidence is circumstantial.

According to UNESCO Director-General Kōichirō Matsuura, a meeting of ambassadors from the 54 member states of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) was conducted.

All OIC states—including Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, three countries that officially recognised the Taliban government—joined the protest to spare the monuments.

[63] Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf sent a delegation led by Pakistan's interior minister Moinuddin Haider to Kabul to meet with Omar and try to prevent the destruction, arguing that it was un-Islamic and unprecedented.

[79] In April 2002, Afghanistan's post-Taliban leader Hamid Karzai called the destruction a "national tragedy" and pledged the Buddhas to be rebuilt.

[78] In September 2005, Mawlawi Mohammed Islam Mohammadi, Taliban governor of Bamyan province at the time of the destruction and widely seen as responsible for its occurrence, was elected to the Afghan Parliament.

Swiss filmmaker Christian Frei made a 95-minute documentary titled The Giant Buddhas on the statues, the international reactions to their destruction, and an overview of the controversy, released in March 2006.

As they waited for the Afghan government and international community to decide when to rebuild them, a $1.3 million UNESCO-funded project was sorting out the chunks of clay and plaster—ranging from boulders weighing several tons to fragments the size of tennis balls—and sheltering them from the elements.

[85][86] In 2015, a wealthy Chinese couple, Janson Hu and Liyan Yu, financed the creation of a Statue of Liberty-size 3D light projection of an artist's view of what the larger Buddha, known as Solsol to locals, might have looked like in its prime.

[89] UNESCO's Afghan operations were stymied, largely due to foreign investors' fears that continued support of cultural preservation projects in the country would run afoul of international sanctions.

Researcher Erwin Emmerling of Technical University Munich announced he believed it would be possible to restore the smaller statue using an organic silicon compound.

It is estimated that roughly half the pieces of the Buddhas can be put back together according to Bert Praxenthaler, a German art historian and sculptor involved in the restoration.

It is felt by some, such as human rights activist Abdullah Hamadi, that the empty niches should be left as monuments to the fanaticism of the Taliban, while others believe the money could be better spent on housing and electricity for the region.

[94] Some people, including Habiba Sarabi, the provincial governor, believe that rebuilding the Buddhas would increase tourism, which would aid the surrounding communities.

[94] After fourteen years, on 7 June 2015, a Chinese adventurist couple Zhang Xinyu and Liang Hong filled the empty cavities where the Buddhas once stood with 3D laser light projection technology.

Despite the Buddhas's destruction, the ruins continue to be a popular culture landmark,[104] bolstered by increasing domestic and international tourism to the Bamyan Valley.

[109] A 2012 novel by Rajesh Talwar titled An Afghan Winter provides a fictional backdrop to the destruction of the Buddhas and its impact on the global Buddhist community.

[111][112] The AD 507 chapter of 2020 novel A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne writes an imaginary account of how the Buddhas were commissioned and built.