Bar Kokhba revolt

In 129/130 CE, Emperor Hadrian founded the pagan colony of Aelia Capitolina on the ruins of Jerusalem, extinguishing hopes for the Temple's restoration and fueling Jewish anger.

The defeat had significant religious and philosophical consequences; Jewish messianic beliefs became more abstract and spiritualized, while rabbinical political thought shifted to a more cautious and conservative approach.

[24] Additional knowledge about the revolt can be gleaned from the coins minted by the rebels, which help to estimate the duration of the uprising and reveal its goals:[19] the establishment of Jewish independence and the rebuilding of the Temple.

[4] A rabbinic version of this story, seemingly set during Hadrian's reign,[34] suggests that the Romans did plan to rebuild the Temple, but a malevolent Samaritan convinced them to abandon the idea, claiming that the Jews would rebel once their city was restored.

[45] According to Martin Goodman, Hadrian established the colony as a "final solution for Jewish rebelliousness," aiming to permanently erase the city and prevent any future rebellion among Jews in Judaea or in diaspora communities, as had occurred under his predecessor.

[58][59] Several elements are believed to have contributed to the rebellion; changes in administrative law, the widespread presence of legally-privileged Roman citizens, alterations in agricultural practice with a shift from landowning to sharecropping, the impact of a possible period of economic decline, and an upsurge of nationalism, the latter influenced by the Diaspora Revolt.

[61] Cassius Dio reports that:The Jews [...] did not dare try conclusions with the Romans in the open field, but they occupied the advantageous positions in the country and strengthened them with mines and walls, in order that they might have places of refuge whenever they should be hard pressed, and might meet together unobserved underground; and they pierced these subterranean passages from above at intervals to let in air and light.Dio's account has been corroborated by the discovery of hundreds of hiding complexes, created in large numbers in almost every populated area.

The Israel Antiques Authority's archaeologists Moran Hagbi and Dr. Joe Uziel speculated "It is possible that a Roman soldier from the Tenth Legion found the coin during one of the battles across the country and brought it to their camp in Jerusalem as a souvenir.

[84] However, Eck's theory on battle in Tel Shalem is rejected by M. Mor, who considers the location implausible given Galilee's minimal (if any) participation in the Revolt and distance from the main conflict flareup in Judea proper.

This is demonstrated by a destruction layer dating from the early 2nd century at Tel Abu al-Sarbut in the Sukkoth Valley,[85] and by abandonment deposits from the same period that were discovered at al-Mukhayyat[86] and Callirrhoe.

This theory was proposed by Werner Eck in 1999, as part of his general maximalist work which did put the Bar Kokhba revolt as a very prominent event on the course of the Roman Empire's history.

The theory for a major decisive battle in Tel Shalem implies a significant extension of the area of the rebellion, with Eck suggesting the war encompassed also northern valleys together with Galilee.

The rabbinic account describes agonizing tortures: Akiva was flayed with iron combs, Ishmael had the skin of his head pulled off slowly, and Haninah was burned at a stake, with wet wool held by a Torah scroll wrapped around his body to prolong his death.

While some claim further resistance was broken quickly, others argue that pockets of Jewish rebels continued to hide with their families into the winter months of late 135 and possibly even spring 136.

[118] In 2021, an ethno-archaeological comparison analysis by Dvir Raviv and Chaim Ben David supported the accuracy of Dio's depopulation claims, describing his account as "reliable" and "based on contemporaneous documentation.

"[123] Jerome provides a similar account: "in Hadrian's reign, when Jerusalem was completely destroyed and the Jewish nation was massacred in large groups at a time, with the result that they were even expelled from the borders of Judaea.

[138] The Tosefta records 2nd century sage Rabbi Ishmael drawing a comparison between the days of the Temple's destruction and the persecutions under Hadrian, when the Romans were "uprooting the Torah" from among the Jews.

[141] Under the argument to ensure the prosperity of the newly founded Roman colony of Aelia Capitolina, Jews were forbidden to enter the city, except on the day of Tisha B'Av.

[116] After Hadrian's death in 138, the Romans scaled back on their crackdown across Judea, but the ban on Jewish entry into Jerusalem remained in place, exempting only those Jews who wished to enter the city for Tisha B'Av.

[145] By destroying the association of Jews with Judea and forbidding the practice of the Jewish faith, Hadrian aimed to root out a nation that had inflicted heavy casualties on the Roman Empire.

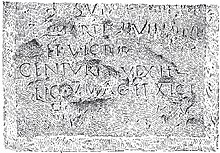

A building inscription of the Sixth Legion from the 2nd century was discovered at as-Salt, which is identified as Gadara, one of the principal Jewish settlements in Perea, and provides more proof of the Roman military presence there.

[citation needed] Eusebius of Caesarea wrote that Christians were killed and suffered "all kinds of persecutions" at the hands of rebel Jews when they refused to help Bar Kokhba against the Roman troops.

[162] The outcome of the Bar Kokhba revolt reinforced the Christian interpretation that the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE signified divine punishment, making it a key argument in anti-Jewish polemics.

[175][176][177] In the belief of restoration to come, in the early 7th century the Jews made an alliance with the Sasanian Empire, joining the invasion of Palaestina Prima in 614 to overwhelm the Byzantine garrison, and briefly gained autonomy in Jerusalem.

Buildings and underground installations carved out beneath or close to towns, such as hiding complexes, burial caves, storage facilities, and field towers, have both been found to have destruction layers and abandonment deposits.

[5] Excavations at archaeological sites such as Horvat Ethri and Khirbet Badd ‘Isa have demonstrated that these Jewish villages were destroyed in the revolt, and were only resettled by pagan populations in the 3rd century.

The ruins of Betar, the last standing stronghold of Bar Kokhba, can be found at Khirbet al-Yahud, an archeological site located in the vicinity of Battir and Beitar Illit.

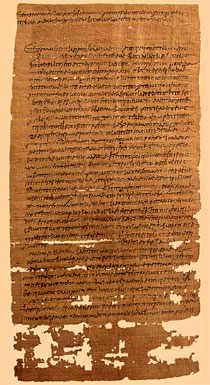

Near the end of the uprising, many Jews fleeing for their life sought asylum in refuge caves, the most of which are found in Israel's Judaean Desert on high cliffs overlooking the Dead Sea and the Jordan Valley.

[citation needed] In 2023, archaeologists discovered a cache consisting of four Roman swords and a pilum concealed within a crevice in a cave located within the Ein Gedi nature reserve.

It has been suggested to attribute these findings to Roman soldiers who took part in the uprising and brought the coins as souvenirs or commemorative relics, or to Jewish captives, slaves or immigrants who arrived in those areas in the aftermath of the revolt.