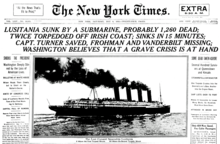

Sinking of the RMS Lusitania

[2] At time of her sinking the primarily passenger-carrying vessel had in her hold around 173 tons of war supplies, comprising 4.2 million rounds of rifle ammunition, almost 5,000 shrapnel-filled artillery shell casings and 3,240 brass percussion fuses.

Desperate to gain an advantage on the Atlantic and define a role for the Navy, and heavily overestimating the effectiveness of the new weapon, the Admiralty under Hugo von Pohl decided to step up its submarine campaign.

Despite a severe shortage of destroyers, Admiral Henry Oliver ordered HMS Louis and Laverock to escort Lusitania, and took the further precaution of sending the Q ship Lyons to patrol Liverpool Bay.

At this time, the Royal Navy was significantly involved with operations leading up to the landings at Gallipoli, and the intelligence department had been undertaking a programme of misinformation to convince Germany to expect an attack on her northern coast.

As part of this, ordinary cross-channel traffic to the Netherlands was halted from 19 April and false reports were leaked about troop ship movements from ports on Britain's western and southern coasts.

[49] Turner adjusted his heading northeast, not knowing that this report related to events of the previous day and apparently thinking submarines would be more likely to keep to the open sea,[23]: 184 or that a sinking would be safer in shallower water.

Many, including author Charles Lauriat, who published his account of the disaster, stated that a few passengers climbed into the early portside lifeboats before being ordered out by Staff Captain James Anderson, who proclaimed, "This ship will not sink" and reassured those nearby that the liner had "touched bottom" and would stay afloat.

First Sea Lord Fisher noted on one document submitted by Webb for review: "As the Cunard company would not have employed an incompetent man its a certainty that Captain Turner is not a fool but a knave.

He had, therefore, approached the Head of Kinsale to obtain a bearing, intending to bring the ship closer to land and then take a course north of the reported submarine a mere half mile away from shore.

Dernburg further said that the warnings given by the German Embassy before her sailing, plus the 18 February note declaring the existence of "war zones" relieved Germany of any responsibility for the deaths of the American citizens aboard.

"[93] In a 13 July report on conditions in Germany, US Ambassador James W. Gerard reported that due to the highly effective propaganda efforts of the Admiralty press bureau: As to Germany’s war methods, they have the full approval of the people; the sinking of the Lusitania was universally approved, and even men like Von Gwinner, head of the German Bank, say they will treat the Mauretania in the same way if she comes out.Propaganda medals were made by a number of artists, including Ludwig Gies and in August 1915, the Munich medallist and sculptor Karl Goetz (Medailleur) [de] (1875–1950).

Of the 159 US citizens aboard Lusitania, over a hundred[4] lost their lives, and there was massive outrage in America, The Nation calling it "a deed for which a Hun would blush, a Turk be ashamed, and a Barbary pirate apologize".

Thus, Dudley Field Malone, Collector of the Port of New York, issued an official denial to the German charges, saying that Lusitania had been inspected before her departure and no guns were found, mounted or unmounted.

This principle the Government of the United States understands the explicit instructions issued on August 3, 1914, by the Imperial German Admiralty to its commanders at sea to have recognized and embodied, as do the naval codes of all other nations, and upon it every traveler and seaman had a right to depend.

With increasing evidence of the ineffectiveness of the U-boat campaign, which was originally promised to force the British to the negotiating table in six weeks, Bethmann Hollweg petitioned the Kaiser to publicly forbid attacks without warning against all passenger ships.

[121] Bachmann was forced to resign, Tirpitz lost direct access to the Kaiser, and the end of unrestricted submarine warfare against passenger ships was made public to the Americans on 1 September.

"[128] According to US Ambassador Walter Hines Page, the British did not want US military help, but they felt America "falls short morally" in insufficiently condemning German methods and character.

Taking advantage of this and the British Admiralty's order of 31 January 1915 that British merchant ships should fly neutral colours as a ruse de guerre,[167] Admiral Hugo von Pohl, commander of the German High Seas Fleet and outgoing Chief of the Admiralty, acted outside of the normal protocols and declared an abandonment of cruiser rules, publishing a warning in the Deutscher Reichsanzeiger (Imperial German Gazette) on 4 February 1915:[168] (1) The waters around Great Britain and Ireland, including the whole of the English Channel, are hereby declared to be a War Zone.

[115][175] In argument with German political leaders during the Arabic crisis, Admiral Bachmann argued that they did not want Britain to adhere to the Declaration of London, as it was more important to be able to continue the submarine attacks and British actions helped justify that.

[177] This explosion has been used to explain the speed of Lusitania's sinking, and has been the subject of debate since the disaster, with the situation of the wreck (lying on top of the site of the torpedo hit) making obtaining definitive answers difficult.

[182] Eyewitness reports, including accounts by the U-boat captain and onlookers who saw a specific lifeboat destroyed, also tend to place the position of the initial torpedo strike far back from the cargo hold.

[60] In the 1960s, American diver John Light dived repeatedly to the site of the shipwreck in efforts to prove the existence of contraband explosives aboard Lusitania's cargo hold, which had been ignited by the torpedo.

[178] In any case, explanations like this and the steam lines theory propose that torpedo damage alone, striking near the boiler rooms, sunk Lusitania quickly without a second substantial explosion,[60] and are strengthened by recent research that found that this blast would be enough to cause, on its own, serious off-centre flooding.

"[189][190] Beesly concludes: "unless and until fresh information comes to light, I am reluctantly driven to the conclusion that there was a conspiracy deliberately to put Lusitania at risk in the hope that even an abortive attack on her would bring the United States into the war.

The cargo included 50 barrels and 94 cases of aluminium (making 46 tons), an unknown quantity of which was in the powdered form used to produce explosives at Woolwich Arsenal,[181] as well as other metals, leather and rubber.

It also may be noted that the British War Office considered the majority of US-manufactured ammunition in this period to be of poor quality and so "suitable for emergency use only", and in any case incapable of supplying consumption of over 5 million rounds per day.

[212] When Senator Robert M. La Follette suggested in 1917 a conspiracy where Wilson was warned that the ship carried 6 million rounds of ammunition, the New York authorities responded by providing him with the correct number.

[217][218] Bailey and Ryan discuss this in detail, noting that it was common knowledge that "dozens of ships" left New York with similar or larger cargoes of small arms ammunition and other military supplies.

While most would agree that running into the submarine was ultimately a matter of bad luck, with the more modern understanding that the ship may have sunk from torpedo damage alone, the degree to which Turner may have exacerbated the loss of life gains greater significance.

She is severely collapsed onto her starboard side as a result of the force with which she slammed into the sea floor, and over decades, Lusitania has deteriorated significantly faster than Titanic because of the corrosion in the winter tides.