Bartolomeo Cristofori

The available source materials on Cristofori's life include his birth and death records, two wills, the bills he submitted to his employers, and a single interview carried out by Scipione Maffei.

[2] Probably the most important event in Cristofori's life is the first one of which we have any record: in 1688, at age 33, he was recruited to work for Prince Ferdinando de Medici.

According to Stewart Pollens, there were already several qualified individuals in Florence who could have filled the position; however, the Prince passed them over and paid Cristofori a higher salary than his predecessor.

He moved rather quickly to Florence (May 1688; his job interview having taken place in March or April), was issued a house, complete with utensils and equipment, by the Grand Duke's administration, and set to work.

[3] At this time, the Grand Dukes of Tuscany employed a large staff of about 100 artisans, who worked in the Galleria dei Lavori of the Uffizi.

This invention may have been meant to fit into a crowded orchestra pit for theatrical performances, while having the louder sound of a multi-choired instrument.

[9] Another document referring to the earliest piano is a marginal note made by one of the Medici court musicians, Federigo Meccoli, in a copy of the book Le Istitutioni harmoniche by Gioseffo Zarlino.

The second will, dated March 23 of the same year, changes the provisions substantially, bequeathing almost all his possessions to the "Dal Mela sisters ... in repayment for their continued assistance lent to him during his illnesses and indispositions, and also in the name of charity."

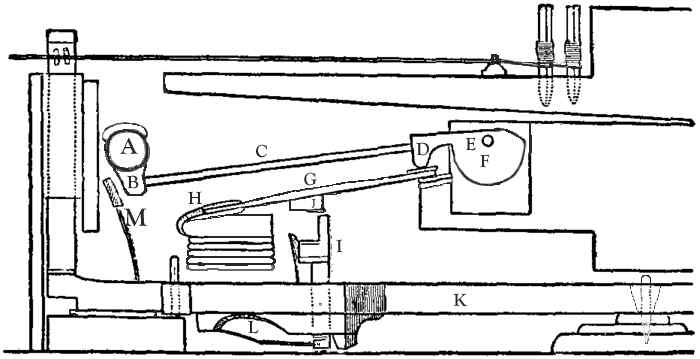

The hammer heads in Cristofori's mature pianos (A) are made of paper, curled into a circular coil and secured with glue, and surmounted by a strip of leather at the contact point with the string.

The purpose of the leather is presumably to make the hammers softer, thus emphasizing the lower harmonics of string vibration by maintaining a broad area of contact at impact.

Cristofori's principle continues to be applied in modern pianos, where the now-enormous string tension (up to 20 tons) is borne by a separate iron frame (the "plate").

Wraight has written that the three surviving Cristofori pianos appear to follow an orderly progression: each has heavier framing than its predecessor.

[12] Thus, it appears that the move toward heavier framing, a trend that dominates the history of the piano, may already have begun in Cristofori's own building practice.

On two of his surviving instruments, Cristofori employed an unusual arrangement of the tuning pins: they are inserted all the way through their supporting wrest plank.

With the nut (front bridge) inverted as well, the blows of the hammers, coming from below, would seat the strings firmly into place, rather than threatening to displace them.

According to musical instrument scholar Grant O'Brien, the inverted wrestplank is "still to be found in pianos dating from a period 150 years after [Cristofori's] death.

[6] Piano making after Cristofori's time ultimately settled consistently on spruce as the best material for soundboards; however, Denzil Wraight has noted some compensating advantages for cypress.

In two of the attested pianos, there is a forerunner of the modern soft pedal: the player can manually slide the entire action four millimeters to one side, so that the hammers strike just one of the two strings ("una corda").

In his combined harpsichord-piano, with two 8-foot strings for each note, Ferrini allowed one set of harpsichord jacks to be disengaged but did not provide a una corda device for the hammer action.

According to Stewart Pollens, "the earlier museum records document that all three [attested] Cristofori pianos were discovered with similar gauges of iron wire through much of the compass, and brass in the bass."

This may indicate that the original strings did indeed include iron ones; however, the breakage might also be blamed on the extensive rebuilding of this instrument, which changed its tonal range.

According to Wraight, it is not straightforward to determine what Cristofori's pianos sounded like, since the surviving instruments (see above) are either too decrepit to be played or have been extensively and irretrievably altered in later "restorations".

The note onsets are not as sharply defined as in a harpsichord, and the response of the instrument to the player's varying touch is clearly noticeable.

Knowledge of how Cristofori's invention was initially received comes in part from the article published in 1711 by Scipione Maffei, an influential literary figure, in the Giornale de'letterati d'Italia of Venice.

Maffei said that "some professionals have not given this invention all the applause it merits," and goes on to say that its sound was felt to be too "soft" and "dull"—Cristofori was unable to make his instrument as loud as the competing harpsichord.

Subsequent technological developments in the piano were often mere "re-inventions" of Cristofori's work; in the early years, there were perhaps as many regressions as advances.

An apparent remnant harpsichord, lacking soundboard, keyboard, and action, is currently the property of the noted builder Tony Chinnery, who acquired it at an auction in New York.

This instrument passed through the shop of the late 19th century builder/fraudster Leopoldo Franciolini, who reworked it with his characteristic form of decoration, but according to Chinnery "there are enough construction details to identify it definitely as the work of Cristofori".

As Stewart Pollens has documented, in late 18th century France it was believed that the piano had been invented not by Cristofori but by the German builder Gottfried Silbermann.

Silbermann was in fact an important figure in the history of the piano, but his instruments relied almost entirely on Cristofori for the design of their hammer actions.