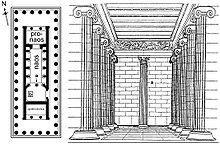

Bassae Frieze

Pausanias[2] records that this last sanctuary was dedicated to Apollo Epikourios (helper or succourer) by the Phigalians in thanks for delivery from the plague of 429 BC.

[6] The frieze was bought at auction by the British Museum in 1815 where it is now on permanent display in a specially constructed room in Gallery 16.

As has been remarked the temple's existence had been known to scholars from the record in Pausanias but its location was uncertain until the accidental discovery in November 1765 by the French architect J. Bocher of the site, but unfortunately he was unable to survey the place due to his murder on his second visit.

Of the informal group of antiquaries who undertook the enterprise[11] it fell to Haller to record the 1812 dig in his field notebook, the two copies of which are the only surviving details of the disposition of the intact site and finds since the drawings he made in 1811 were lost at sea.

Furthermore, the early explorers of the temple make little discussion of the sculpture in their subsequent publications, it was not until 1892 that they were formally published with Arthur Smith's catalogue of the British Museum's holdings.

[13] The site was explored in 1812 by British antiquaries who removed the twenty-three slabs of the Ionic cella frieze and transported them to Zante along with other sculptures.

Cockerell decorated the walls of the Ashmolean Museum's Great Staircase and that of the Travellers Club with plaster casts of the same frieze.

[14] The frieze was purchased by the British Museum from James Linkh, Thomas Legh, Karl Haller von Hallerstein, George Christian Gropius, John Foster and Charles Robert Cockerell who had bought it at auction.

Cooper and Madigan make a further distinction of the Trojan and Heraklean Amazonomachies following on from their determination of the blocks' arrangement.

Yet contrary to customary practice these three scenes are not on separate sides of the building, but run continuously around the entablature with the only clear disjuncture at the northwest corner.

Here a bearded Greek, wearing a chiton, a cuirass, a helmet, and a baldric and carrying a shield, seizes an Amazon by the hair while trampling her underfoot.

The final slab in the series, BM 539, represents the moment when a truce has been called between the Greeks and Amazons in order to clear the battlefield of equipment, the wounded and the dead.

These elements more commonly belong to a different scene in the Centauromachy narrative – the brawl at the wedding feast of Peirithoos.

Homer relates the events of Polypites birth and the attack of the centaurs,[25] when the ritual procession to gift a girdle in the sanctuary of Artemis is interrupted.

While nearing the sanctuary, the procession is set upon by a gang of centaurs, precipitating a brawl, much as had happened at the wedding feast.

Although they face in opposite directions, their poses are nearly identical, differing only in that one, BM 526:2, folds his lower left leg under the thigh as he kneels on the back of his adversary.

On the next slab, BM 524, the goal of the procession, the ritual sanctuary of Artemis, is indicated by a tree hung with a lion or panther skin in thanksgiving for a successful hunt.

The left leg of the woman who gestures with extended arms, BM 524:4, reaches backward below the statue, where the base would be.

As the centaur pulls the garment off her proper left shoulder, it passes behind her neck but does not appear between her nude torso and the statue.

Appropriately for this kind of disorganized fight, the centaur attack employs weapons and tactics alien to the hoplites' traditional mode of combat.

Emblematic of this portion of the Centauromachy is the death of Kaineus, BM 530, where the hero, invulnerable to conventional weapons, is disposed of by being buried alive.

13), like that of the south that faces it, depicts the most important part of the action and is segregated from the rest of its subject by its compositional unity.

On the three slabs at the south, groups balance one another in axial symmetry around the prominent central figure of Herakles, who stands above the Corinthian column.

This centrifugal design brings to a halt the right-to-left movement of the spectator around the cella at the point where the frieze ends and he leaves the temple.

On the first pair of slabs at the north, Artemis has arrived in her chariot drawn by stags, with her brother Apollo, who has already alighted and draws his bow, BM 523.

The rightward movement of the divine pair continue in the woman, the lint centaur, and the hoplite on the slab at the comer, BM 522.

The two pairs of slabs that form the north part of the frieze share the same general figural pattern.

Cockerell also decorated the walls of the Ashmolean Museum's Great Staircase and that of the Travellers Club with plaster casts of the same frieze.

The wealthy landowner Thomas Legh was one of the excavators of the temple[26][27] and a plaster cast copy of the frieze is displayed in the Bright Gallery of Lyme Hall, Cheshire, one of his stately homes.