Bathhouse Row

The bathhouses are a collection of turn-of-the-century eclectic buildings in neoclassical, renaissance-revival, Spanish and Italianate styles aligned in a linear pattern with formal entrances, outdoor fountains, promenades, and other landscape-architectural features.

[3] The bathhouse industry went into a steep decline during the mid-20th century as advancements in medicine made bathing in natural hot springs appear less believable as a remedy for illness.

[7] Services begin with a "Whirlpool Mineral Bath" for $35.00[8] The cream-colored brick building is neoclassical in style with the base, spandrels, friezes, cornices and the parapet finished in white stucco.

[3] Friezes above the two-story doric columns have medallions (paterae) that frame the brass lettered words "Buckstaff Baths" centered above the entrance.

The third floor is a common space containing reading and writing rooms and access to the roof-top sun porches at the north and south ends of the building.

Its surpassing elegance was intentional, as Samuel W. Fordyce waited to observe the Maurice's construction to find out if he could build "a more attractive and convenient" facility.

[10] The third floor houses a massive ceramic-tiled Hubbard Currence therapeutic tub (a full body immersion whirlpool installed in 1938 when other hydrotherapeutic pools were also added), areas for men' s and women' s parlors, and a wood panelled gymnasium to the rear.

After experiencing the curative powers of the thermal waters in treating a Civil War injury, he moved to Hot Springs and was involved in numerous businesses including the Arlington and Eastman Hotels, several bathhouses, a theater, the horsecar line, and utilities.

[12] The Lamar Bathhouse was completed in 1923 in a transitional style often used in clean-lined commercial buildings of the time that were still not totally devoid of elements left over from various classical revivals: symmetry, cornices, and vague pediments articulating the front entrance.

The building was remodeled in 1915, following a design by George Mann and Eugene John Stern of Little Rock, which added the front sun parlor and made the white hygienic appearance warmer and more luxurious.

A therapeutic pool was installed in the Maurice in 1931 to treat various forms of paralysis (spurred on by Franklin Delano Roosevelt's treatments at Warm Springs, Georgia).

[3] At this time it was also the first of the Hot Springs bathhouses to provide specialized treatment for polio and other severe muscular and joint problems, being the only one to employ a registered physical therapist.

The third floor houses the dark-panelled Roycroft Den, named after Elbert Hubbard's New York Press, which promoted the Arts and Crafts movement in the United States.

It provided special services, elegant appointments, and luxurious decor to attract sophisticated bathers who came to Hot Springs to fraternize with their peers.

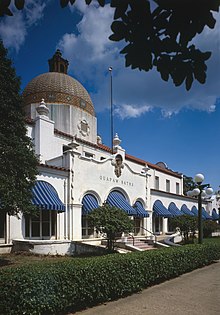

The two-story 37-room Spanish Colonial Revival building, approximately 14,000 square feet (1,300 m2), is constructed of brick and concrete masonry finished with stucco.

The structure is trapezoidal in plan, although the impressive front elevation is symmetrically designed with twin towers composed of three-tiered setbacks flanking the main entrance.

It was renamed Quapaw Bathhouse in honor of a local Native American tribe that briefly held the surrounding territory after the Louisiana Purchase was made.

Originally the symbol was used to represent Santiago de Campostela, the patron saint of Spain, but it evolved into a mere decorative element in secular revival buildings such as this.

[3] Work began in August 2007 to ready the building for its new use with pools added so that whole families can enjoy the spring water together and the bathhouse re-opened to the public in 2008.

The well-detailed building has a simplified Spanish Baroque doorway framed by pilasters topped with frieze, cornice and finials flanking a second story window.

The two bronze federal eagles on their stone pillars still stand guard over the old entrance, forming a gateway to the concrete path that leads between the two bathhouses up to the baroque double staircase of the balustrade.

In local Indian mythology the valley of the hot springs was considered neutral ground, a healing place and the sacred territory of the Great Spirit.

By the start of the 20th century, Hot Springs became an attraction for fashionable people all over the world to visit and partake of the baths, while maintaining its reputation as a healing place for the sickly.

In 1916, Stephen Mather, director of the National Park Service, brought landscape architect Jens Jensen down from Chicago to enhance Bathhouse Row.

George Mann and Eugene John Stern of Little Rock were hired in 1917 to do a comprehensive plan of Bathhouse Row to guide its future development.

[28] The more formally aligned Grand Promenade at the rear of the bathhouses, begun in the 1930s and completed in the 1960s, replaced the meandering Victorian path and changed the architectural character of area.

[11] These were finally rendered obsolete by the discovery of penicillin and its widespread manufacture after World War II allowed syphilis to be effectively and reliably cured.

The free use of Greek, Roman, Spanish and Italian architectural idioms emphasize the high style sought after by the planners and create a strong sense of place.

[3] What remains on Bathhouse Row are the architectural remnants of a bygone era when bathing was considered an elegant pastime for the rich and famous and a path to well-being for those with various ailments.

[3] Pickup truck enthusiasts have enjoyed the vintage neighborhood during Saturday night cruising among the steaming manholes and free water fountains.