Battle of Hastings

It took place approximately 7 mi (11 km) northwest of Hastings, close to the present-day town of Battle, East Sussex, and was a decisive Norman victory.

The background to the battle was the death of the childless King Edward the Confessor in January 1066, which set up a succession struggle between several claimants to his throne.

William founded a monastery at the site of the battle, the high altar of the abbey church supposedly placed at the spot where Harold died.

[1] Their settlement proved successful,[2][b] and they quickly adapted to the indigenous culture, renouncing paganism, converting to Christianity,[3] and intermarrying with the local population.

Edward was childless and embroiled in conflict with the formidable Godwin, Earl of Wessex, and his sons, and he may also have encouraged Duke William of Normandy's ambitions for the English throne.

[15][d] In early 1066, Harold's exiled brother Tostig Godwinson raided southeastern England with a fleet he had recruited in Flanders, later joined by other ships from Orkney.

Advancing on York, the Norwegians occupied the city after defeating a northern English army under Edwin and Morcar on 20 September at the Battle of Fulford.

Harald Hardrada and Tostig were killed, and the Norwegians suffered such great losses that only 24 of the original 300 ships were required to carry away the survivors.

The most famous claim is that Pope Alexander II gave a papal banner as a token of support, which only appears in William of Poitiers's account, and not in more contemporary narratives.

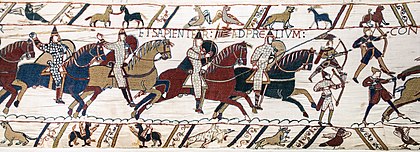

The couched lance, carried tucked against the body under the right arm, was relatively new and probably not used at Hastings, as the terrain was unfavourable for long cavalry charges.

[64] Harold camped at Caldbec Hill on the night of 13 October, near a "hoar-apple tree", about 8 mi (13 km) from William's castle at Hastings.

The exact events preceding the battle are obscure, with contradictory accounts in the sources, but all agree that William's army advanced from his castle towards the enemy.

[66] Harold had taken a defensive position at the top of Senlac Hill (present-day Battle, East Sussex), about 6 mi (9.7 km) from William's castle at Hastings.

Within 40 years, the battle was described by the Anglo-Norman chronicler Orderic Vitalis as "Senlac",[n] a Norman-French adaptation of the Old English word "Sandlacu", which means "sandy water".

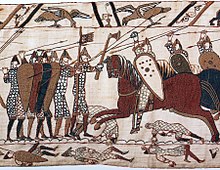

[86] Harold's forces deployed in a small, dense formation at the top of a steep slope,[84] with their flanks protected by woods and marshy ground in front of them.

[90] The cavalry was held in reserve,[95] and a small group of clergymen and servants situated at the base of Telham Hill was not expected to take part in the fighting.

[90] William's disposition of his forces implies that he planned to open the battle with archers in the front rank weakening the enemy with arrows, followed by infantry who would engage in close combat.

The uphill angle meant that the arrows either bounced off the shields of the English or overshot their targets and flew over the top of the hill.

William of Poitiers states that the bodies of Gyrth and Leofwine were found near Harold's, implying that they died late in the battle.

The military historian Peter Marren speculates that if Gyrth and Leofwine died early in the battle, that may have influenced Harold to stand and fight to the end.

[103] It is not known how many assaults were launched against the English lines, but some sources record various actions by both Normans and Englishmen that took place during the afternoon's fighting.

It occurred at a small fortification or set of trenches where some Englishmen rallied and seriously wounded Eustace of Boulogne before being defeated by the Normans.

[113] Modern historians have pointed out that one reason for Harold's rush to battle was to contain William's depredations and keep him from breaking free of his beachhead.

[113] William was the more experienced military leader,[116] and in addition, the lack of cavalry on the English side allowed Harold fewer tactical options.

Of the named Normans who fought at Hastings, one in seven is stated to have died, but these were all noblemen, and the death rate among the common soldiers was probably higher.

Although scholars thought for a long time that remains would not be recoverable, due to the acidic soil, recent finds have changed this view.

[126][y] One story relates that Gytha, Harold's mother, offered the victorious duke the weight of her son's body in gold for its custody, but was refused.

He ruthlessly put down the various risings, culminating in the Harrying of the North in late 1069 and early 1070 that devastated parts of northern England.

According to 12th-century sources, William made a vow to found the abbey, and the high altar of the church was placed at the site where Harold had died.

[135] The topography of the battlefield has been altered by subsequent construction work for the abbey, and the slope defended by the English is now much less steep than it was at the time of the battle; the top of the ridge has also been built up and levelled.