Battle of France

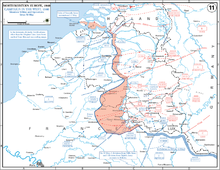

The remaining Allied divisions in France, sixty French and two British, made a determined stand on the Somme and Aisne rivers but were defeated by the German combination of air superiority and armoured mobility.

The neutral Vichy government led by Marshal Philippe Pétain replaced the Third Republic and German military occupation began along the French North Sea and Atlantic coasts and their hinterlands.

[34] Hitler recognised the necessity of military campaigns to defeat the Western European nations, preliminary to the conquest of territory in Eastern Europe, to avoid a two-front war but these intentions were absent from Directive N°6.

[38] Hitler ordered a conquest of the Low Countries to be executed at the shortest possible notice to forestall the French and prevent Allied air power from threatening the industrial area of the Ruhr.

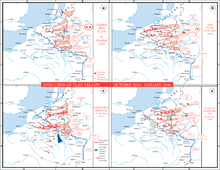

[41] Fall Gelb entailed an advance through the middle of Belgium; Aufmarschanweisung N°1 envisioned a frontal attack, at a cost of half million German soldiers to attain the limited goal of throwing the Allies back to the River Somme.

[42] When Hitler raised objections to the plan and wanted an armoured breakthrough, as had happened in the invasion of Poland, Halder and Brauchitsch attempted to dissuade him, arguing that while the fast-moving mechanised tactics were effective against a "shoddy" Eastern European army, they would not work against a first-rate military like the French.

Brauchitsch replied that the military had yet to recover from the Polish campaign and offered to resign; this was refused but two days later Hitler postponed the attack, giving poor weather as the reason for the delay.

[47] Halder's plan satisfied no-one; General Gerd von Rundstedt, the commander of Army Group A (Heeresgruppe A) recognised that it did not adhere to the classic principles of Bewegungskrieg (war of manoeuvre) that had guided German strategy since the 19th century.

In late September, Gamelin issued a directive to Général d'armée Gaston Billotte, commander of the 1st Army Group, ...assuring the integrity of the national territory and defending without withdrawing the position of resistance organised along the frontier....giving the 1st Army Group permission to enter Belgium, to deploy along the Escaut according to Plan E. On 24 October, Gamelin directed that an advance beyond the Escaut was only feasible if the French moved fast enough to forestall the Germans.

[62] By late 1939, the Belgians had improved their defences along the Albert Canal and increased the readiness of the army; Gamelin and Grand Quartier Général (GQG) began to consider the possibility of advancing further than the Escaut.

[75] The Germans enjoyed an advantage through the theory of Auftragstaktik (mission command) by which officers, NCOs and men were expected to use their initiative and had control over supporting arms, rather than the slower, top-down methods of the Allies.

[94] Only French heavy tanks generally carried wireless but these were unreliable, hampering communication and making tactical manoeuvre difficult, compared to German units.

[108] The French command reacted immediately, sending the 1st Army Group north in accordance with Plan D. This move committed their best forces, diminishing their fighting power by the partial disorganisation it caused and their mobility by depleting their fuel stocks.

Success in the Battle of Stonne and the recapture of Bulson would have enabled the French to defend the high ground overlooking Sedan and bombard the bridgehead with observed artillery-fire, even if they could not take it.

Most of the BEF and the French First Army were still 100 km (60 mi) from the coast but despite delays, British troops were sent from England to Boulogne and Calais just in time to forestall the XIX Corps panzer divisions on 22 May.

On 17 June, Junkers Ju 88s – mainly from Kampfgeschwader 30 – sank a "10,000 tonne ship", the 16,243 GRT liner RMS Lancastria off St Nazaire, killing about 4,000 Allied troops and civilians.

[215] Mussolini felt the conflict would soon end and he reportedly said to the army Chief-of-Staff, Marshal Pietro Badoglio, "I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference as a man who has fought".

[citation needed] Discouraged by his cabinet's hostile reaction to a British proposal for a Franco-British union to avoid defeat and believing that his ministers no longer supported him, Reynaud resigned on 16 June.

[219] After listening to the reading of the preamble, Hitler left the carriage in a calculated gesture of disdain for the French delegates and negotiations were turned over to Wilhelm Keitel, the chief of staff of OKW.

From 1937 to 1940, Hitler gave his views on events, their importance and his intentions, then defended them against contrary opinion from the likes of the former Chief of the General Staff Ludwig Beck and Ernst von Weizsäcker.

He wrote that, given public reluctance to contemplate another war and a need to reach consensus about Germany, the rulers of France and Britain were reticent (to resist German aggression), which limited dissent at the cost of enabling assumptions that suited their convenience.

[223] May wrote that when Hitler demanded a plan to invade France in September 1939, the German officer corps thought that it was foolhardy and discussed a coup d'état, only backing down when doubtful of the loyalty of the soldiers to them.

After the Mechelen Incident, OKH devised an alternative and hugely risky plan to make the invasion of Belgium a decoy, switch the main effort to the Ardennes, cross the Meuse and reach the Channel coast.

The French Dyle-Breda variant of the Allied deployment plan was based on an accurate prediction of German intentions, until the delays caused by the winter weather and shock of the Mechelen Incident, led to the radical revision of Fall Gelb.

The insularity of the French and British intelligence agencies meant that had they been asked if Germany would continue with a plan to attack across the Belgian plain after the Mechelen Incident, they would not have been able to point out how risky the Dyle-Breda variant was.

More items were obtained about invasions of Switzerland or the Balkans, while German behaviour consistent with an Ardennes attack, such as the dumping of supplies and communications equipment on the Luxembourg border or the concentration of Luftwaffe air reconnaissance around Sedan and Charleville-Mézières, was overlooked.

[226] According to May, French and British rulers were at fault for tolerating poor performance by the intelligence agencies; that the Germans could achieve surprise in May 1940, showed that even with Hitler, the process of executive judgement in Germany had worked better than in France and Britain.

Prioux thought that a counter-offensive could still have worked up to 19 May but by then, roads were crowded with Belgian refugees when they were needed for redeployment and the French transport units, which performed well in the advance into Belgium, failed for lack of plans to move them back.

[229] The British Chiefs of Staff Committee had concluded in May 1940 that if France collapsed, "we do not think we could continue the war with any chance of success" without "full economic and financial support" from the United States.

It was well equipped and well supplied despite the economic disruption brought by the occupation thanks to Lend-Lease and grew from 500,000 men in the summer of 1944 to over 1,300,000 by V-E day, making it the fourth largest Allied army in Europe.