Battle of Adwa

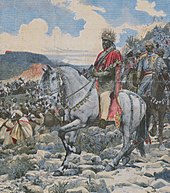

The Ethiopian army managed to defeat the heavily outnumbered invading Italian and Eritrean force led by Oreste Baratieri on March 1, 1896, near the town of Adwa.

The Amharic version of the article, however, stated that the Emperor could use the good offices of the Kingdom of Italy in his relations with foreign nations if he wished.

However, the Italian diplomats claimed that the original Amharic text included the clause and that Menelik II knowingly signed a modified copy of the Treaty.

Baratieri delayed making a decision for a few more hours, claiming that he needed to wait for some last-minute intelligence, but in the end announced that the attack would start the next morning at 9:00am.

While these included elite Bersaglieri and Alpini units, a large proportion of the troops were inexperienced conscripts recently drafted from metropolitan regiments in Italy into newly formed "d'Africa" battalions for service in Africa.

Additionally, a limited number of troops were from the Cacciatori d'Africa; units permanently serving in Africa and in part recruited from Italian settlers.

[19][20] According to historian Chris Prouty: They [the Italians] had inadequate maps, old-model guns, poor communication equipment and inferior footgear for the rocky ground.

Budget restrictions and supply shortages meant that many of the rifles and artillery pieces issued to the Italian reinforcements sent to Africa were obsolete models, while clothing and other equipment was often substandard.

[29] On the night of 29 February and the early morning of 1 March, three Italian brigades advanced separately towards Adwa over narrow mountain tracks, while a fourth remained camped.

Unbeknownst to General Baratieri, Emperor Menelik knew his troops had exhausted the ability of the local peasants to support them and had planned to break camp the next day (2 March).

The Emperor had risen early to begin prayers for divine guidance when spies from Ras Alula, brought him news that the Italians were advancing.

However, he inadvertently marched his command into a narrow valley where the Wollo Oromo cavalry under Ras Mikael slaughtered his brigade, shouting 'Ebalgume!

Dabormida's remains were never found, although an old woman living in the area said that she had given water to a mortally wounded Italian officer, "a chief, a great man with spectacles and a watch, and golden stars".

[37][36][38] The retreating columns under Baratieri were harried for nine miles before the Ethiopian cavalry gave up the pursuit, fires were then lit on the highest hilltops to signal local peasants to attack Italian and Ascari stragglers.

"[39] George Berkeley records that the Italian casualties were approximately 6,100 men killed: 261 officers, 2,918 white NCOs and privates, with 954 permanently missing, and about 2,000 ascari dead.

[43] As Paul B. Henze notes, "Baratieri's army had been completely annihilated while Menelik's was intact as a fighting force and gained thousands of rifles and a great deal of equipment from the fleeing Italians.

[45][46] Augustus Wylde records that when he visited the battlefield months after the battle, the pile of severed hands and feet was still visible, "a rotting heap of ghastly remnants.

Wylde wrote how the neighborhood of Adwa "was full of their freshly dead bodies; they had generally crawled to the banks of the streams to quench their thirst, where many of them lingered unattended and exposed to the elements until death put an end to their sufferings.

Chris Prouty notes that Albertone was given into the care of Azaj Zamanel, commander of Empress Taytu's personal army, and "had a tent to himself, a horse and servants".

Families began sending to the newspapers letters they had received before Adwa in which their menfolk described their poor living conditions and their fears at the size of the army they were going to face.

"[57] Lewis believes that it "was his farsighted certainty that total annihilation of Baratieri and a sweep into Eritrea would force the Italian people to turn a bungled colonial war into a national crusade"[58] that stayed his hand.

Almost forty years later, on 3 October 1935, after the League of Nations's weak response to the Abyssinia Crisis, the Italians launched a new military campaign endorsed by Benito Mussolini, the Second Italo-Ethiopian War.

This time the Italians employed vastly superior military technology such as tanks and aircraft, as well as chemical warfare, and the Ethiopian forces were defeated by May 1936.

[60] On a similar note, the Ethiopian historian Bahru Zewde observed that "few events in the modern period have brought Ethiopia to the attention of the world as has the victory at Adwa".

Italy's government who had viewed them as an inferior barbaric race were brought to their knees and subsequently forced to recognize the African nation of Ethiopia as an equal.

Indeed, one student of Ethiopia's History, Donald N. Levine, points out that for the Italians Adwa "became a national trauma which demagogic leaders strove to avenge.

Levine also noted that the victory "gave encouragement to isolationist and conservative strains that were deeply rooted in Ethiopian culture, strengthening the hand of those who would strive to keep Ethiopia from adopting techniques imported from the modern West – resistances with which both Menelik and Haile Selassie would have to contend".

In Addis Ababa, the Victory of Adwa is celebrated at Menelik Square with the presence of government officials, patriots, foreign diplomats and the general public.

[63][64] The beloved and influential wife of Emperor Menelik II, Empress Taytu Betul, played a significant role during the Battle of Adwa.

Of particular note are Ejigayehu Shibabaw's ballad dedicated to the Battle of Adwa and Teddy Afro's popular song "Tikur Sew", which literally translates to "black man or black person" – a poetic reference to Emperor Menelik II's decisive African victory over Europeans, as well as the Emperor's darker skin complexion.