Battle of Agincourt

In the ensuing campaign, many soldiers died from disease, and the English numbers dwindled; they tried to withdraw to English-held Calais but found their path blocked by a considerably larger French army.

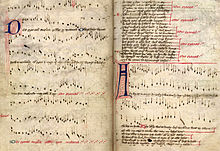

The English eyewitness account comes from the anonymous author of the Gesta Henrici Quinti, believed to have been written by a chaplain in the King's household who would have been in the baggage train at the battle.

[19] A recent re-appraisal of Henry's strategy of the Agincourt campaign incorporates these three accounts and argues that war was seen as a legal due process for solving the disagreement over claims to the French throne.

The English had very little food, had marched 260 miles (420 km) in two and a half weeks, were suffering from sickness such as dysentery, and were greatly outnumbered by well-equipped French men-at-arms.

[37] Henry, worried about the enemy launching surprise raids, and wanting his troops to remain focused, ordered all his men to spend the night before the battle in silence, on pain of having an ear cut off.

The Burgundian sources have him concluding the speech by telling his men that the French had boasted that they would cut off two fingers from the right hand of every archer, so that he could never draw a longbow again.

[39] The French army had 10,000 men-at arms[40][41][42] plus some 4,000–5,000 miscellaneous footmen (gens de trait) including archers, crossbowmen[43] (arbalétriers) and shield-bearers (pavisiers), totaling 14,000–15,000 men.

Probably each man-at-arms would be accompanied by a gros valet (or varlet), an armed servant, adding up to another 10,000 potential fighting men,[7] though some historians omit them from the number of combatants.

[49] On account of the lack of space, the French drew up a third battle, the rearguard, which was on horseback and mainly comprised the varlets mounted on the horses belonging to the men fighting on foot ahead.

The French monk of St. Denis says: "Their vanguard, composed of about 5,000 men, found itself at first so tightly packed that those who were in the third rank could scarcely use their swords,"[64] and the Burgundian sources have a similar passage.

The deep, soft mud particularly favoured the English force because, once knocked to the ground, the heavily armoured French knights had a hard time getting back up to fight in the melee.

[32] This entailed abandoning his chosen position, in which the longbowmen were defended from cavalry charges by long sharpened wooden stakes set in the ground and pointed towards the French lines.

French chroniclers agree that when the mounted charge did come, it did not contain as many men as it should have; Gilles le Bouvier states that some had wandered off to warm themselves and others were walking or feeding their horses.

Juliet Barker quotes a contemporary account by a monk from Saint Denis Basilica who reports how the wounded and panicking horses galloped through the advancing infantry, scattering them and trampling them down in their headlong flight from the battlefield.

He considered a knight in the best-quality steel armour invulnerable to an arrow on the breastplate or top of the helmet, but vulnerable to shots hitting the limbs, particularly at close range.

Then they had to walk a few hundred yards (metres) through thick mud and a press of comrades while wearing armour weighing 50–60 pounds (23–27 kg), gathering sticky clay all the way.

[84] The surviving French men-at-arms reached the front of the English line and pushed it back, with the longbowmen on the flanks continuing to shoot at point-blank range.

When the archers ran out of arrows, they dropped their bows and, using hatchets, swords, and the mallets they had used to drive their stakes in, attacked the now disordered, fatigued and wounded French men-at-arms massed in front of them.

[88] The only French success was an attack on the lightly protected English baggage train, with Ysembart d'Azincourt (leading a small number of men-at-arms and varlets plus about 600 peasants) seizing some of Henry's personal treasures, including a crown.

Barker, following the Gesta Henrici, believed to have been written by an English chaplain who was actually in the baggage train, concluded that the attack happened at the start of the battle.

[63] Le Fèvre and Wavrin similarly say that it was signs of the French rearguard regrouping and "marching forward in battle order" which made the English think they were still in danger.

[95] Among them were 90–120 great lords and bannerets killed, including[97] three dukes (Alençon, Bar and Brabant), nine counts (Blâmont, Dreux, Fauquembergue, Grandpré, Marle, Nevers, Roucy, Vaucourt, Vaudémont) and one viscount (Puisaye), also an archbishop.

[111] Juliet Barker, Jonathan Sumption and Clifford J. Rogers criticized Curry's reliance on administrative records, arguing that they are incomplete and that several of the available primary sources already offer a credible assessment of the numbers involved.

Mortimer also considers that the Gesta vastly inflates the English casualties – 5,000 – at Harfleur, and that "despite the trials of the march, Henry had lost very few men to illness or death; and we have independent testimony that no more than 160 had been captured on the way".

Rogers says each of the 10,000 men-at-arms would be accompanied by a gros valet (an armed, armoured and mounted military servant) and a noncombatant page, counts the former as fighting men, and concludes thus that the French in fact numbered 24,000.

[125] Other ballads followed, including "King Henry Fifth's Conquest of France", raising the popular prominence of particular events mentioned only in passing by the original chroniclers, such as the gift of tennis balls before the campaign.

[132] Critic David Margolies describes how it "oozes honour, military glory, love of country and self-sacrifice", and forms one of the first instances of English literature linking solidarity and comradeship to success in battle.

[132][133] Partially as a result, the battle was used as a metaphor at the beginning of the First World War, when the British Expeditionary Force's attempts to stop the German advances were widely likened to it.

[134] Shakespeare's portrayal of the casualty loss is ahistorical in that the French are stated to have lost 10,000 and the English 'less than' thirty men, prompting Henry's remark, "O God, thy arm was here".

[136] In his 2007 film adaptation, director Peter Babakitis uses digital effects to exaggerate realist features during the battle scenes, producing a more avant-garde interpretation of the fighting at Agincourt.