Battle of Bladensburg

However, warships of the Royal Navy led by Rear Admiral George Cockburn, second in command of the North American Station, controlled Chesapeake Bay from early 1813 onwards and had captured large numbers of U.S. trading vessels.

Although Cockburn withdrew from Chesapeake Bay late in 1813, his sailors had taken soundings and even placed buoys to mark channels and sandbars, in preparation for a renewed campaign in 1814.

[8] By April 1814, Napoleon had been defeated and was exiled to the island of Elba off the coast of Italy, and large numbers of British ships and troops were now free to be used to prosecute the former backwater war with the United States.

[9] Most of the newly available troops went to the continental colonies of British North America where Lieutenant General Sir George Prevost (who was Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief in and over the Provinces of Upper-Canada, Lower-Canada, Nova-Scotia, and New-Brunswick, and their several Dependencies, Vice-Admiral of the same, Lieutenant-General and Commander of all His Majesty’s Forces in the said Provinces of Lower Canada and Upper-Canada, Nova-Scotia and New-Brunswick, and their several Dependencies, and in the islands of Newfoundland, Prince Edward, Cape Breton and the Bermudas, &c. &c. &c.') was preparing to lead an invasion into New York from the Canadas, heading for Lake Champlain and the upper Hudson River.

The intention was for this force to carry out raids on the Atlantic Seaboard to "effect a diversion on the coasts of the United States of America in favor [sic] of the army employed in the defence of Upper and Lower Canada".

Nevertheless, on 2 July, Madison designated the area around Washington and Baltimore as the United States Army's Tenth Military District and, without consulting Armstrong, appointed Brigadier General William H. Winder as its commander.

Armstrong did not provide him with any staff, and despite his fears that the British could launch an attack against almost any point with very little warning, Winder did not order any field fortifications to be constructed, nor make any other preparations.

Ross's troops landed at Benedict on 19 August, and began marching upstream the following day, while Cockburn proceeded up the river with ships' boats and small craft.

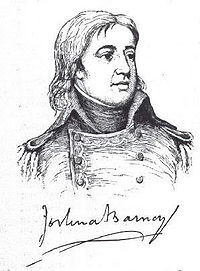

By 21 August, Ross had reached Nottingham, and Commodore Joshua Barney was forced to destroy the gunboats and other sailing craft of the Chesapeake Bay Flotilla the next day, and retreat overland towards Washington.

On the night of 23–24 August, at the urging of Rear Admiral Cockburn and some of the British Army officers under his own command, Ross decided to risk an attack on Washington.

In Washington, Brigadier General Winder could call in theory upon 15,000 militia, but he actually had only 120 dragoons and 300 other regulars, plus 1,500 poorly trained and under-equipped militiamen at his immediate disposal.

Instead of strengthening his commanding position, he immediately decamped and marched his exhausted troops across Bladensburg bridge, which he did not burn, to a brickyard 1.5 miles (2.4 km) further on.

Meanwhile, in Washington, every government department was hastily packing its records and evacuating them to Maryland or Virginia, in requisitioned or hired carts or river boats.

The artillery was posted in an earthwork hastily constructed by Colonel Decius Wadsworth, the Army's Commissary General of Ordnance, to the north of the bridge.

The Maryland militia infantry regiments were posted in a line of battle south of the earthwork, too far away to protect the artillery and exposed to British fire.

(Barney had originally been posted to guard the lower bridge over the Eastern Branch and destroy it if necessary, but he had pleaded to President Madison and the Secretary of the Navy that he and his men were needed where the action was.

When Minor prevailed on Winder to order muskets to be distributed on the morning of the battle, the junior officer responsible for issuing their flints insisted that they be returned and recounted.

Had he held Lowndes Hill, Stansbury could have made the British approach a costly one (although this would have involved fighting with the East Branch at his back, which would not have improved his men's morale and might have been disastrous in a hasty retreat).

[34] Pinkney, whose elbow was shattered by a musket ball,[35] was driven back and as Thornton's men closed in, the Baltimore artillerymen retreated with five of their cannon, being forced to spike and abandon another.

[36] As the 5th Maryland exchanged fire with British infantry in cover on three sides, Schutz's and Ragan's conscripted militia broke and fled under a barrage of rockets.

Winder issued confused orders for three of Captain Burch's guns to fall back rather than cover Sterrett's retreat, and the 5th Maryland and the rest of Stansbury's brigade fled the field, sweeping most of Lavall's horsemen with them.

Thornton's light brigade made several frontal attacks over the creek, but were repulsed three times by artillery fire, and were counter-attacked by Barney's detachment.

[39] Smith's brigade fell back initially in good order, but Winder's orders to retreat apparently did not reach Barney, and his situation worsened when the civilian drivers of the carts carrying his reserve ammunition joined the general rout,[40] leaving the Marine gun crews with fewer than three rounds of canister, round shot and charges in their caissons.

Barney's 300 sailors and 103 Marines nevertheless held off the British frontal attacks, launching counter-attacks armed with hand pikes and cutlasses, with cries of "Board'em!

[43] The efforts of British commander Robert Ross during the battle deserve praise, according to journalist Steve Vogel, in his book about that era.

Thirty-three incoming patients recorded in August and September 1814 were American seamen, soldiers, and marines wounded from Bladensburg or subsequent engagements.

Lieutenant General Prevost had urged Vice Admiral Cochrane to avenge the raid on Port Dover on the north shore of Lake Erie earlier in the year, in which the undefended settlement had been set ablaze by American troops.

In fact, there was little or no looting or wanton destruction of private property by Ross's troops or Cochrane's sailors during the advance and the occupation of Washington.

However, when the British later withdrew to their ships in the Patuxent, discipline was less effective (partly because of fatigue) and there was considerable looting by foraging parties and by stragglers and deserters.

"[54] “Anecdotal accounts from the time period suggest that anywhere from 15 to 50 percent of any given U.S. naval vessel’s crew were of African descent”[55] The exact number of black sailors in the War of 1812 is difficult for historians to determine, since "navy muster rolls rarely mention race or ethnicity.