Battle of Bunker Hill

[13] The battle led the British to adopt a more cautious planning and maneuver execution in future engagements, which was evident in the subsequent New York and New Jersey campaign.

The costly engagement also convinced the British of the need to hire substantial numbers of Hessian auxiliaries to bolster their strength in the face of the new and formidable Continental Army.

[26][27] On the night of June 16, colonial Colonel William Prescott led about 1,200 men onto the peninsula in order to set up positions from which artillery fire could be directed into Boston.

[33] He promptly ordered his men to begin constructing a breastwork running down the hill to the east, deciding that he did not have the manpower to also build additional defenses to the west of the redoubt.

[43] Prescott ordered the Connecticut men under Captain Knowlton to defend the left flank, where they used a crude dirt wall as a breastwork and topped it with fence rails and hay.

Low tide opened a gap along the Mystic River to the north, so they quickly extended the fence with a short stone wall to the water's edge.

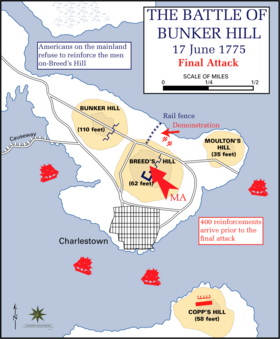

[47] Further reinforcements arrived just before the battle, including portions of Massachusetts regiments of Colonels Brewer, Nixon, Woodbridge, Little, and Major Moore, as well as Callender's company of artillery.

[54] General Howe led the light infantry companies and grenadiers in the assault on the American left flank along the rail fence, expecting an easy effort against Stark's recently arrived troops.

[57] Howe had intended the advance to be preceded by an artillery bombardment from the field pieces present, but it was soon discovered that these cannon had been supplied with the wrong caliber of ammunition, delaying the assault.

The regulars were loaded down with gear wholly unnecessary for the attack, and the British troops were overheating in their wool uniforms under the heat of the afternoon sun, compounded by the nearby inferno from Charlestown.

Pigot's attacks on the redoubt and breastworks fared little better; by stopping and exchanging fire with the colonists, the regulars were fully exposed and suffered heavy losses.

[73] The third attack was made at the point of the bayonet and successfully carried the redoubt; however, the final volleys of fire from the colonists cost the life of Major Pitcairn.

[77] General Putnam attempted to reform the troops on Bunker Hill; however, the flight of the colonial forces was so rapid that artillery pieces and entrenching tools had to be abandoned.

[89] King George's attitude hardened toward the colonies, and the news may have contributed to his rejection of the Continental Congress' Olive Branch Petition, the last substantive political attempt at reconciliation.

[91] Gage wrote another report to the British Cabinet in which he repeated earlier warnings that "a large army must at length be employed to reduce these people" which would require "the hiring of foreign troops".

Dearborn accused General Putnam of inaction, cowardly leadership, and failure to supply reinforcements during the battle, which subsequently sparked a major controversy among veterans of the war and historians.

[102] The colonial fortifications were haphazardly arrayed; it was not until the morning that Prescott discovered that the redoubt could be easily flanked,[33] compelling the hasty construction of a rail fence.

[45] The front lines of the colonial forces were generally well-managed, but the scene behind them was significantly disorganized, at least in part due to a poor chain of command and logistical organization.

[68] Colonel Prescott was of the opinion that the third assault would have been repulsed, had his forces in the redoubt been reinforced with more men, or if more supplies of ammunition and powder had been brought forward from Bunker Hill.

[106] Gage and Howe decided that a frontal assault on the works would be a simple matter, although an encircling move, gaining control of Charlestown Neck, would have given them a more rapid and resounding victory.

The impetus of any British attack was further diluted when officers opted to concentrate on firing repeated volleys which were simply absorbed by the earthworks and rail fences.

[111] Historian John Ferling maintains that, had General Gage used the Royal Navy to secure the narrow neck to the Charleston peninsula, cutting the Americans off from the mainland, he could have achieved a far less costly victory.

But he was motivated by revenge over patriot resistance at the Battles of Lexington and Concord and relatively heavy British losses, and he also felt that the colonial militia were completely untrained and could be overtaken with little effort, opting for a frontal assault.

The idea dates originally to the general-king Gustavus Adolphus (1594–1632) who gave standing orders to his musketeers "never to give fire, till they could see their own image in the pupil of their enemy's eye".

[117] The earliest similar quotation came from the Battle of Dettingen on June 27, 1743, where Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Andrew Agnew of Lochnaw warned the Royal Scots Fusiliers not to fire until they could "see the white of their e'en.

[119] Whether or not it was actually said in this battle, it was clear that the colonial military leadership were regularly reminding their troops to hold their fire until the moment when it would have the greatest effect, especially in situations where their ammunition would be limited.

[128] Lt. Col. Seth Read, who served under John Paterson at Bunker Hill, went on to settle Geneva, New York and Erie, Pennsylvania, and was said to have been instrumental in the phrase E pluribus unum being added to U.S.

The painting shows a number of participants in the battle including a British officer, John Small, among those who stormed the redoubt, yet came to be the one holding the mortally wounded Warren and preventing a fellow redcoat from bayoneting him.

[140] In nearby Cambridge, a small granite monument just north of Harvard Yard bears this inscription: "Here assembled on the night of June 16, 1775, 1200 Continental troops under command of Colonel Prescott.

[149] On June 16 and 17, 1875, the centennial of the battle was celebrated with a military parade and a reception featuring notable speakers, among them General William Tecumseh Sherman and Vice President Henry Wilson.

Left stamp depicts Battle of Bunker Hill battle flag and Monument

Left-center, depicts John Trumbull's painting of the battle

Right-center depicts detail of Trumbull's painting

Right depicts image of Bunker Hill battle flag