Battle of Caseros

Instead, Urquiza, suspicious that the warmongering was a ploy to delay the writing of an Argentine constitution, began to make plans of his own and negotiated loans from the Brazilians when he decided to rebel.

[12] When he felt it was most opportune, he released a statement from Concepción del Uruguay known as his Pronuniciamiento, calling for the resignation of Rosas.

The Brazilians imposed a harsh price on the Montevideo government for their help, annexing a northern strip of the nation and forcing them to declare Brazil the guarantor of Uruguyan independence.

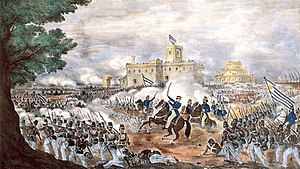

In compliance with the treaty, Urquiza led a joint army and crossed Morón creek, positioning his forces in Monte Caseros.

Leadership was confused as his appointed commander Angel Pacheco resigned due to contradictory micromanagement and incompetence on Rosas's part.

[15] In the end, Rosas, an aging politician more suited to administration than warfare, decided to take personal command of the battle.

Because he was not an experienced or skilled commander, he made no effort to scout for a good battle position, and simply waited for the allies to come to him.

[16] Among his captains were Jerónimo Costa, who defended Martín García island from the French in 1838; Martiniano Chilavert, a former opponent of Rosas who defected when his fellows allied themselves with foreigners; Hilario Lagos, veteran from the campaign against the Indians of 1833.

[17] Due to the poor morale and the desertion of commanders, most notably that of Ángel Pacheco, the Argentine army had already been thinned when the battle began.

[19] Among their ranks were people who would later become prominent figures, such as future presidents Bartolomé Mitre and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento.

It has only been forty days since we crossed the rapids of the Paraná river on the Diamante, and we are already near the city of Buenos Aires, and facing our enemies, where we will now fight for freedom and glory!

Meanwhile, the Brazilian infantry, supported by a Uruguayan brigade and an Argentine cavalry squadron seized the Palomar, a circular building near the right of the Rosista line and used for pigeon breeding, still standing to this day.

Remarkably, although this was a modern battle that lasted relatively long in a tight area, the casualties were relatively light for that era: only 4% of the troops who fought were killed or wounded in the fighting.

Later on, many of the members of the Rosista repression squads known as the Mazorca were tried and executed, including Ciriaco Cuitiño and Leandro Antonio Alén.

Alén was the father of Leandro N. Alem, later radical caudillo, and the grandfather of Hipólito Yrigoyen, later president of Argentina.