Battle of the Chesapeake

The battle was strategically decisive,[1] in that it prevented the Royal Navy from reinforcing or evacuating the besieged forces of Lieutenant General Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia.

He sailed south from Sandy Hook, New Jersey, outside New York Harbor, with 19 ships of the line and arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake early on 5 September to see de Grasse's fleet already at anchor in the bay.

The battle was consequently fairly evenly matched, although the British suffered more casualties and ship damage, and it broke off when the sun set.

The British forces were led at first by the turncoat Benedict Arnold, and then by William Phillips before General Charles, Earl Cornwallis, arrived in late May with his southern army to take command.

In June, Cornwallis marched to Williamsburg, where he received a confusing series of orders from General Sir Henry Clinton that culminated in a directive to establish a fortified deep-water port (which would allow resupply by sea).

[8] The presence of these British troops, coupled with General Clinton's desire for a port there, made control of the Chesapeake Bay an essential naval objective for both sides.

[9][10] On 21 May, Generals George Washington and Rochambeau, respectively the commanders of the Continental Army and the Expédition Particulière, met at the Vernon House in Newport, Rhode Island to discuss potential operations against the British and Loyalists.

Sailing outside the normal shipping lanes to avoid notice, he arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on 30 August,[12] and disembarked the troops to assist in the land blockade of Cornwallis.

[3] Meanwhile, his colleague and commander of the New York fleet, Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Graves, had spent several weeks trying to intercept a convoy organized by John Laurens to bring much-needed supplies and hard currency from France to Boston.

[15] When Hood arrived at New York, he found that Graves was in port (having failed to intercept the convoy), but had only five ships of the line that were ready for battle.

Barras sailed from Newport on 27 August with 8 ships of the line, 4 frigates, and 18 transports carrying French armaments and siege equipment.

Washington and Rochambeau, in the meantime, had crossed the Hudson on 24 August, leaving some troops behind as a ruse to delay any potential move on the part of General Clinton to mobilize assistance for Cornwallis.

[3] His progress was slow; the poor condition of some of the West Indies ships (contrary to claims by Admiral Hood that his fleet was fit for a month of service) necessitated repairs en route.

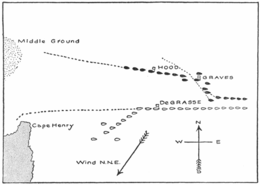

When the true size of the fleets became apparent, Graves assumed that de Grasse and Barras had already joined forces, and prepared for battle; he directed his line toward the bay's mouth, assisted by winds from the north-northeast.

[2] He faced the difficult proposition of organizing a line of battle while sailing against an incoming tide, with winds and land features that would require him to do so on a tack opposite that of the British fleet.

The angle of approach of the British line also played a role in the damage they sustained; ships in their van were exposed to raking fire when only their bow guns could be brought to bear on the French.

"[30] The Diadème, according to a French officer "was utterly unable to keep up the battle, having only four thirty-six-pounders and nine eighteen-pounders fit for use" and was badly shot up; she was rescued by the timely intervention of the Saint-Esprit.

[41] In a council held that day, the British admirals decided against attacking the French, due to "the truly lamentable state we have brought ourself.

King George III wrote (well before learning of Cornwallis's surrender) that "after the knowledge of the defeat of our fleet [...] I nearly think the empire ruined.

[51] General Washington acknowledged to de Grasse the importance of his role in the victory: "You will have observed that, whatever efforts are made by the land armies, the navy must have the casting vote in the present contest.

In a major engagement that ended Franco-Spanish plans for the capture of Jamaica in 1782, he was defeated and taken prisoner by Rodney in the Battle of the Saintes.

[53] His flagship Ville de Paris was lost at sea in a storm while being conducted back to England as part of a fleet commanded by Admiral Graves.

Graves, despite the controversy over his conduct in this battle, continued to serve, rising to full admiral and receiving an Irish peerage.

Instead, he maintained, "the British fleet should be as compact as possible, in order to take the critical moment of an advantage opening ..."[55] Others criticise Hood because he "did not wholeheartedly aid his chief", and that a lesser officer "would have been court-martialled for not doing his utmost to engage the enemy.

"[42] Admiral Rodney was critical of Graves' tactics, writing, "by contracting his own line he might have brought his nineteen against the enemy's fourteen or fifteen, [...] disabled them before they could have received succor, [... and] gained a complete victory.

[58] According to scientist/historian Eric Jay Dolin, the dreaded hurricane season of 1780 in the Caribbean (a year earlier) may have also played a crucial role in the outcome of the 1781 naval battle.

The Royal Navy's loss of 15 warships with 9 severely damaged crucially affected the balance of the American Revolutionary War, especially during Battle of Chesapeake Bay.

An outnumbered British Navy losing to the French proved decisive in Washington's Siege of Yorktown, forcing Cornwallis to surrender and effectively securing independence for the United States of America.