Battle of Crysler's Farm

The battle arose from a United States military campaign that was intended to capture Montreal in the British province of Lower Canada.

Major General James Wilkinson's division of 8,000 was to concentrate at Sackett's Harbor on Lake Ontario, and proceed down the Saint Lawrence River in gunboats, batteaux and other small craft.

At some point, they would rendezvous with a division of 4,000 under Major General Wade Hampton advancing north from Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain, to make the final attack on Montreal.

Until the last minute, the planner were uncertain whether the objective was to be Montreal or Kingston, as Armstrong originally intended to attack and where the British naval squadron on Lake Ontario was based.

Chiefly though, neither force could apparently carry sufficient supplies to sustain itself before Montreal, making a siege or any prolonged blockade impossible.

He decided that the defences on this obvious route were too strong and instead shifted westward to Four Corners, on the Chateauguay River near the border with Lower Canada.

[10] The poor prospects for success (and possibly his own illness)[6] led Armstrong to abandon his intention of leading the final assault himself.

[11] Wilkinson's force left Sackett's Harbor in 300 batteaux and other small craft[12] on 17 October, bound at first for Grenadier Island at the head of the St. Lawrence.

Mid-October was very late in the year for serious campaigning in the Canadas and the American force was hampered by bad weather, losing several boats and suffering from sickness and exposure.

British brigs and gunboats under Commander William Mulcaster had left Kingston to rendezvous with and escort batteaux and canoes carrying supplies up the Saint Lawrence.

The troops and ammunition were disembarked and marched around Ogdensburg on the south bank of the river, while the lightened boats ran past the British batteries under cover of darkness and poor visibility.

The next day, while the main body re-embarked, an advance guard battalion commanded by colonels Alexander Macomb and Winfield Scott, followed by a battalion of riflemen under Major Benjamin Forsyth were landed on the Canadian side of the river near Point Iroquois to clear the river bank of harassing Dundas County Militia, who were reported to have turned "every narrow stretch of the waterway" from Leeds to Glengarry into "a shooting gallery".

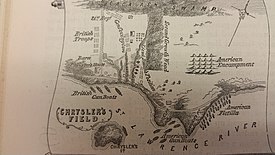

Late on 10 November, after a day spent marching under intermittent fire from British gunboats and field guns, Wilkinson set up his headquarters in Cook's Tavern, with Boyd's troops bivouacked in the surrounding woods.

[20] The British had been aware of the American concentration at Sackett's Harbor, but for a long time they had believed, with good reason, that their own main naval base at Kingston was the intended target of Wilkinson's force.

When Mulcaster returned from French Creek late on 5 November with news that the Americans were heading down the Saint Lawrence, de Rottenburg dispatched a Corps of Observation after them, in accordance with orders previously issued by Governor General Sir George Prevost.

They departed from Kingston in thick weather late on 7 November[22] and evaded the ships of Commodore Isaac Chauncey, which were blockading the base, among the Thousand Islands at the head of the Saint Lawrence River.

The terrain was mainly open fields, which gave full scope to British tactics and musketry, while the muddy ground (planted with fall wheat) and the marshy nature of the woods surrounding the farm would hamper the American manoeuvres.

[23] Half a dozen Canadian Militia dragoons bolted back to the main British force, calling that the Americans were attacking.

[23] At about 10:30 a.m., Wilkinson received a message from Jacob Brown, who reported that the previous evening he had defeated 500 Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders militia at the Battle of Hoople's Creek and the way ahead was clear.

On the American right, the 21st U.S. Infantry under Colonel Eleazer Wheelock Ripley advanced and drove the British skirmish line back through the woods, for almost a mile.

Ripley and Coles resumed their advance along the edge of the woods, but were startled to see a line of redcoats (the 2nd/89th, on Morrison's left flank) rise up out of concealment and open fire.

Legend has it that at this point, Covington mistook the battle-hardened 49th Regiment in their grey greatcoats for Canadian Militia and called out to his men, "Come on, my lads!

The 49th made a charge in awkward echelon formation, suffering heavy casualties from the American guns as they struggled across several rail fences.

Under heavy fire from the 49th, Pearson's detachment and Jackson's two guns, the dragoons renewed their charge twice but eventually fell back, leaving 18 killed and 12 wounded (out of 130).

He subsequently faced a court martial on various charges of negligence and misconduct during the Saint Lawrence Campaign, but was exonerated when most of the government's witnesses refused to testify.

[40] On the British side, Mulcaster was promoted to post-captain to take command of a frigate but lost a leg in 1814 during the Raid on Fort Oswego, ending his active career.

Morrison, Harvey and Pearson all eventually became generals, as did Major James B. Dennis, who commanded the militia which fought Brown at Hoople's Creek.

[44] On the occasion of the bicentennial of the battle (11 November 2013) Prime Minister Stephen Harper visited the Crysler's Farm Battlefield Park on Remembrance Day and laid a wreath at the cenotaph in the presence of contingents from the Royal 22e Régiment, the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders and Les Voltigeurs de Québec as well as representatives from First Nations who fought there.