Battle of Dogger Bank (1915)

After the British victory, both navies replaced officers who were thought to have shown poor judgement and made changes to equipment and procedures because of failings observed during the battle.

The Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine (SKM) was captured from the German light cruiser SMS Magdeburg after she ran aground in the Baltic Sea on 26 August 1914.

[3] The German-Australian steamer Hobart was seized near Melbourne, Australia on 11 August and the Handelsverkehrsbuch (HVB) codebook, used by the German navy to communicate with merchant ships and within the High Seas Fleet, was captured.

This lack of naval experience caused Oliver to make personal decisions about the information to be passed to other departments, many of which, particularly the Operations Division, had reservations about the value of Room 40.

This signals intelligence meant that the British did not need wasteful defensive standing patrols and sweeps of the North Sea but could economise on fuel and use the time for training and maintenance.

[7] With the German High Seas Fleet (HSF) confined to port after the British success at the Battle of Heligoland Bight in 1914, Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, the Commander-in-Chief of the HSF planned a raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby on the east coast of England, with the I Scouting Group (Admiral Franz von Hipper), a battlecruiser squadron of three battlecruisers and a large armoured cruiser, supported by light cruisers and destroyers.

[8][9] The Germans had made the first successful attack on Britain since the 17th century and suffered no losses but Ingenohl was unjustly blamed for missing an opportunity to inflict a defeat on the Royal Navy, despite creating the chance by his offensive-mindedness.

In 1921, the official historian Julian Corbett wrote, Two of the most efficient and powerful British squadrons...knowing approximately what to expect...had failed to bring to action an enemy who was acting in close conformity with our appreciation and with whose advanced screen contact had been established.

On 30 December, the commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, gave orders that when in contact with German ships, officers were to treat orders from those ignorant of local conditions as instructions only, but he and Beatty declined to implement Admiralty suggestions to loosen ship formations, for fear of decentralising tactical command too far.

Buoyed by the success of the raid on the English coast, Admiral Hipper planned an attack on the British fishing fleet on the Dogger Bank.

The German fleet had increased in size since the outbreak of war, with the arrival in service of the König-class dreadnought battleships SMS König, Grosser Kurfürst, Markgraf and Kronprinz of the 3rd Battle Squadron and the Derfflinger-class battlecruiser Derfflinger.

The reconnaissance and British activity at the Dogger Bank led Ingenohl to order Hipper and the I Scouting Group to survey the area and surprise and destroy any light forces found there.

[1] Sighting the smoke from a large approaching force, Hipper headed south-east by 07:35 to escape but the battlecruisers were faster than the German squadron, which was held back by the slower armoured cruiser Blücher and the coal-fuelled torpedo boats.

Chasing the Germans from a position astern and to starboard, the British ships gradually caught up—some reaching a speed of 27 kn (31 mph; 50 km/h)—and closed to gun range.

[16] No warships had engaged at such long ranges or at such high speeds before, and accurate gunnery for both sides was an unprecedented challenge but after a few salvos, British shells straddled Blücher.

Tiger's fire was ineffective, as she mistook the shell splashes from Lion for her own, when the fall of shot was 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) beyond Seydlitz.

[18] At 09:43, Seydlitz was hit by a 13.5 in (340 mm) shell from Lion, which penetrated her after turret barbette and caused an ammunition fire in the working chamber.

This fire spread rapidly through other compartments, igniting ready propellant charges all the way to the magazines and knocked out both rear turrets with the loss of 165 men.

At 10:41, Lion narrowly escaped a disaster similar to that on Seydlitz, when a German shell hit the forward turret and ignited a small ammunition fire but it was extinguished before causing a magazine explosion.

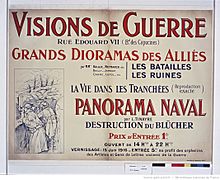

[29][2] British ships began to rescue survivors, but they were hindered by the arrival of the Zeppelin L-5 (LZ-28) and a German seaplane which attacked with small bombs.

As she crept home, the ship suffered further engine-trouble from saltwater contamination in the boiler-feed-water system and her speed dropped to 8 kn (9.2 mph; 15 km/h).

At 17:00, the voyage resumed, the ships eventually managing 10 kn (12 mph; 19 km/h) and when the Grand Fleet arrived, Jellicoe increased the screen to thirteen light cruisers and 67 destroyers.

[33] Lion was out of action for four months, Fisher having decreed that the damage be repaired at Armstrong's on the Tyne, without her going into dry dock, making for an extremely difficult and time-consuming job.

[34] The surviving German ships reached port; Derfflinger was repaired by 17 February but Seydlitz needed a drydock and was not ready for sea until 1 April.

[38] (In 1920, Scheer wrote that the number of British ships present suggested that they had known about the operation in advance, but that this was put down to circumstances, although "other reasons" could not be excluded.

Had Moore's three fast battlecruisers pursued Hipper's remaining three (leaving the slower Indomitable behind as Beatty intended), the British might have been at a disadvantage and been defeated.

Rear-Admiral Moore was quietly replaced and sent to the Canary Islands and Captain Henry Pelly of Tiger was blamed for not taking over when Lion was damaged.