Siege of Fort William Henry

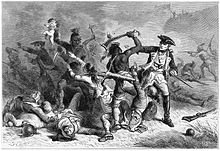

They killed and scalped numerous soldiers and civilians, took as captives women, children, servants, and slaves, and slaughtered sick and wounded prisoners.

[5] Whether or not Montcalm and the other French officers present encouraged or opposed the actions of their Indian allies, and the total number of victims remains a matter of historical debate.

A major expedition by General Edward Braddock in 1755 ended in disaster, and British military leaders were unable to mount any campaigns the following year.

In a major setback, a French and Indian army, led by General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, captured the garrison and destroyed fortifications at the Battle of Fort Oswego in August 1756.

It called for a purely-defensive postures along the frontier with New France, including the contested corridor of the Hudson River and Lake Champlain between Albany and Montreal.

"[10] Loudoun's plan depended on the expedition's timely arrival at Quebec so that French troops would not have the opportunity to move against targets on the frontier, and would instead be needed to defend the heartland of Canada along the Saint Lawrence River.

[11] However, political turmoil in London over the progress of the Seven Years' War in North America and in Europe resulted in a change of power, with William Pitt the Elder rising to take control over military matters.

[12] When Pitt's instructions finally reached Loudoun in March 1757, they called for the expedition to target Louisbourg on the Atlantic coast of Île Royale, which is now known as Cape Breton Island.

[17] The idea was further supported by the French questioning deserters and captives who had been taken during periodic scouting and raiding expeditions, which both sides conducted, including one resulting in the January Battle on Snowshoes.

[18] As early as December 1756, New France's governor, the Marquis de Vaudreuil, began the process of recruiting Indians for the following summer's campaign.

Fueled by stories circulated by Indian participants in the capture of Oswego, the drive was highly successful by drawing nearly 1,000 warriors from the Pays d'en Haut, the more remote regions of New France, to Montreal by June 1757.

Composed primarily of colonial troupes de la marine, militia, and Indians and without heavy weapons, they besieged the fort for four days, destroyed outbuildings and many watercraft, and retreated.

Combined with the troupes de la marine, militia companies, and the arriving Indians, the force accumulated at Carillon amounted to 8,000 men.

[25] In another prelude of things to come, many prisoners were taken on 23 July in the Battle of Sabbath Day Point, and some of whom were also ritually cannibalized before Montcalm managed to convince the Indians instead to send the captives to Montreal to be sold as slaves.

[26] Webb, who commanded the area from his base at Fort Edward, received intelligence in April that the French were accumulating resources and troops at Carillon.

Swearing Putnam and his rangers to secrecy, Webb returned to Fort Edward, and on 2 August, he sent Lieutenant Colonel John Young with 200 regulars and 800 Massachusetts militia to reinforce the garrison at William Henry.

Early on the morning of 3 August, Lévis and the Canadians blocked the road between Edward and William Henry, skirmishing with the recently arrived Massachusetts militia.

The effect of the garrison's return fire was limited to driving French guards from the trenches, and some of the fort's guns either were dismounted or burst owing to the stress of use.

[32] The terms of surrender were that the British and their camp followers would be allowed to withdraw, under French escort, to Fort Edward with full honours of war if they refrained from fighting for 18 months.

As the British marched off, they were harassed by the swarming Indians, who snatched at them, grabbed for weapons and clothing, and pulled away with force those that resisted their actions, including many of the women, children, servants, and slaves.

[34] At last with great difficulty the troops got from the Retrenchment, but they were no sooner out than the savages fell upon our rear, killing and scalping, which occasioned an order for a halt, done in great confusion at last, but, as soon as those in the front knew what was doing in the rear they again pressed forward, and thus the confusion continued & encreased till we came to the advanced guard of the French, the savages still carrying away Officers, privates, women and children, some of which later they kill'd & scalpt in the road.

This horrid scene of blood and slaughter obliged our officers to apply to the French Guard for protection, which they refus'd told them they must take to the woods and shift for themselves.Estimates of the numbers killed, wounded, and captives vary widely.

Many reasons have been proposed justifying his decision, including the departure of many but not all of the Indians, a shortage of provisions, the lack of draft animals to assist in the portage to the Hudson, and the need for the Canadian militia to go home in time to participate in the harvest.

On 27 September, a small British fleet left Quebec and carried paroled or exchanged prisoners taken in a variety of actions, including those at Fort William Henry and Oswego.

The first is the record compiled by Montcalm, including the terms of surrender and his letters to Webb and Loudoun, which received wide publication in the colonies (both French and British) and in Europe.

[49] Yale College President Timothy Dwight, in a history published that was posthumously in 1822, apparently coined the phrase "massacre at Fort William Henry," based on Carver's work.

Montcalm and the French leaders repeatedly promised the Indians opportunities for the glory and trophies of war, including plunder, scalping, and the taking of captives.

According to Steele, that decision bred resentment, as it appeared that the French were conspiring with their enemies, the British, against their friends, the Indians, who were left without any of the promised war trophies.

[52] Part of the site was scientifically excavated in 1953 by archaeologist Stanley Gifford, and again in the 1990s by a forensic anthropological team lead by Maria Liston and Brenda Baker.

[53] The latter study found that diseases, in particular smallpox, inflluenza and tuberculosis brought more casualties than acts of war - with forensic anthropologist Maria Liston declaring that their findings show a group in worse shape and with more pathologies than anything she had ever worked with.