Battle of Front Royal

The Battle of Front Royal, also known as Guard Hill or Cedarville, was fought on May 23, 1862, during the American Civil War, as part of Jackson's Valley campaign.

Jackson attacked the position at Front Royal on May 23, surprising the Union defenders, who were led by Colonel John Reese Kenly.

The Confederate attack was repulsed,[1] but it still was considered concerning enough to return the rest of Banks's command to the Valley and to hold another corps at Manassas, Virginia, depriving McClellan's campaign of about 60,000 men.

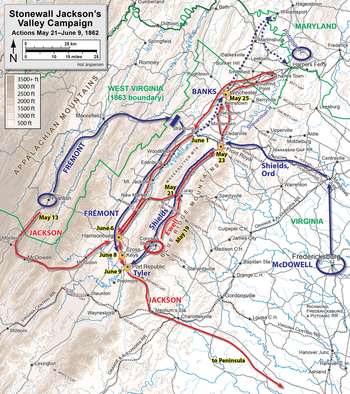

Leaving Ewell and his men to face Banks,[1] Jackson took his troops southwest towards McDowell, Virginia, in early May to confront a Union force commanded by Major General John C. Frémont.

Part of Frémont's command led by Brigadier General Robert H. Milroy attacked Jackson's men on May 8 in the Battle of McDowell.

By then, part of Banks's force had again been transferred out of the Valley,[1] and on May 12, the division of Brigadier General James Shields was ordered east.

[6] Between Jackson and Ewell's forces, the Confederates nominally had 17,000 men,[1] although historian Gary Ecelbarger estimates that due to desertion and straggling the true number of effective was closer to 12,000 or 14,000.

By taking Front Royal, Jackson could sever Banks's communications to the east and then get into the rear of the Strasburg position, either capturing it or forcing its abandonment.

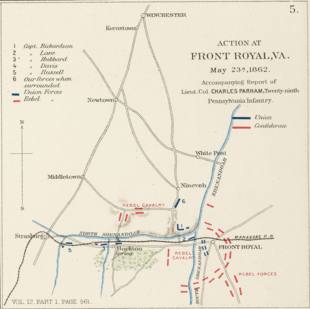

[12] Front Royal and Strasburg were separated by about 12 miles (19 km) on the more direct railroad route, although longer paths existed on roads.

Colonel[a] Turner Ashby's cavalry was sent between Front Royal and Strasburg to cut telegraph lines and the railroad to prevent Union forces from moving between the two towns.

Unaware that he greatly outnumbered the Union force in Front Royal, Jackson decided against attacking from the direct route, the Luray Road.

[16] Ecelbarger suggests that the decision to concentrate on a single road would also prevent Union escapees from Front Royal from providing Banks with an accurate estimate of the size of Jackson's command.

The Confederate Maryland regiment had recently had an incident with mutiny, but Colonel Bradley T. Johnson made a patriotic speech that energized the unit.

[35] The Confederates were able to put out the fires on the South Fork bridge, and Jackson sent aides to bring up the artillery and Stonewall Brigade left at Asbury's Chapel.

While the commander of the Stonewall Brigade, Brigadier General Charles Sidney Winder, had put his men and the artillery in march behind the rest of the Confederate troops, they were still too far to the rear to be available for the fighting at Front Royal.

[36] Kenly reformed his command on Guard Hill across the North Fork, while many of the Confederates became disorganized and plundered the abandoned Union camp.

[42] Making a stand about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north of Cedarville,[43] Kenly deployed his artillery, and ordered the New York cavalrymen to charge.

[51] Cozzens places Jackson's losses (excluding Ashby's action) at 36 men killed and wounded, while stating that Kenly's force suffered 773 casualties, of which 691 were as prisoners.

[10] A Union soldier, William Taylor, was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1897 for his actions in the bridge-burning at Front Royal and in the later Battle of Weldon Railroad.

While leaving the field at Cross Keys to rejoin Jackson, Ewell's men burned a bridge to prevent Frémont from joining forces with Shields.

With Shields and Frémont withdrawing, Jackson was able to take his force from the Shenandoah Valley and join Lee's army for the Seven Days battles.