Battle of Grand-Reng

The two French forces failed to cooperate effectively; Desjardin's troops did all the fighting while Charbonnier's soldiers sat idle nearby.

Historian Ramsey Weston Phipps noted that Pichegru's failure to ensure unity of command was in "defiance of common sense", all the more so because his own success depended on cooperation between the different wings of his army.

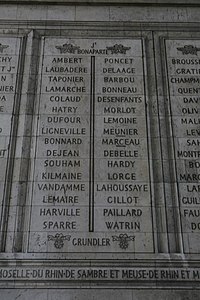

In fact, Pichegru usually allowed Joseph Souham and Jean Victor Marie Moreau to direct the activities of his left wing.

Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany and François Sébastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt commanded 30,000 troops of the right wing, spread from Nieuport to Denain.

The extreme left was formed by Johann Peter Beaulieu's 8,000 men at Arlon and Ernst Paul Christian von Blankenstein's 9,000 soldiers at Trier.

The bulk of the left wing was near Bettignies with a 2,000-man garrison in Charleroi and an observation force of 5,000 men under Karl von Riese watching the crossings of the Sambre and Meuse Rivers.

Leaving 5,000 troops to guard the Philippeville to Beaumont road, Charbonnier's army was to march via Thuillies and cross the Sambre to the east of Thuin.

[7] A detachment under Claude Vezú was directed farther east to observe the Le Tombe entrenched camp southwest of Charleroi.

[8] The commandant of Maubeuge, Jean Dominique Favereau met with Desjardin on 6 May and the two arranged for Éloi Laurent Despeaux's division to be shifted to a position between Cerfontaine and Colleret.

Jacques Fromentin's division marched from Avesnes-sur-Helpe to Jeumont, leaving one brigade under Anne Charles Basset Montaigu at Avesnes.

On 9 May an advance guard of one cavalry regiment, five infantry battalions and a half company of light artillery was formed and assigned to Guillaume Philibert Duhesme.

[9]With everything in readiness, the representatives on mission Louis Antoine de Saint-Just and Philippe-François-Joseph Le Bas decided that Pichegru had been too hasty in ordering the offensive.

The officials reluctantly gave their assent to the military plan and wrote a letter to the Committee of Public Safety explaining the decision.

The regular elements of Jacob's division were made up of the 26th Light and 172nd Line Infantry Demi Brigades, 2nd and 10th Hussar and 11th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiments.

In response to the Austrian general's request for reinforcements, Coburg sent him six battalions and eight squadrons led by Franz von Werneck plus 10 artillery pieces.

From left to right, these were Despeaux moving on Hantes (Hantes-Wihéries), Muller on Valmont (Fontaine-Valmont), Fromentin on Lobbes, Duhesme and Hardy converging on Thuin, Jacob on Aulne Abbey and Dessaubaz (leading Marceau's division) on Montigny-le-Tilleul.

After some brisk clashes, footholds were seized on the north bank by Duhesme's and Hardy's columns at Thuin and by Fromentin's division at Lobbes.

Franz von Reyniac covered Fontaine-l'Évêque with two battalions and one squadron, while Jean Charles Pierre Hennequin de Fresnel held Mont-sur-Marchienne near Charleroi.

[22] Together, Duhesme and Fromentin cleared the Coalition forces out of the woods after an all-day struggle in a persistent rain that caused many muskets to misfire.

Kaunitz massed his forces in three main bodies at Merbes-le-Château, Rouveroy and Péchant (Peissant) while directing Kienmayer to slow the French advance.

After some skirmishing, Duhesme and Fromentin pressed back Kienmayer to the west and uncovered the river crossings in front of Muller's division.

To replace Werneck's division at Bettignies, Prince Coburg reluctantly sent Maximilian Anton Karl, Count Baillet de Latour with six battalions and eight squadrons.

Kaunitz massed the bulk of his troops on a ridge 800 metres (875 yd) southwest of Rouveroy with a battalion of the Ulrich Kinsky Regiment Nr.

[29] On the French left, the divisions of Muller and Despeaux carried some outer defenses east of Grand-Reng, but were unable to capture the village itself.

Due to the bad condition of the roads, the heavier French cannons were unable to get forward quickly enough to suppress the enemy bombardment.

[32] With Fromentin's troops falling back, the Coalition forces tried to exploit the resulting gap by attacking Muller's exposed right flank.

Having shot away most of their ammunition, the tired and hungry French soldiers began to give way in disorder and Desjardin issued orders to retreat.

[36] Historian Victor Dupuis attributed the French defeat to the inactivity of the Army of the Ardennes and to Desjardin's mistaken belief that he was outnumbered when he actually had a superiority of 35,000 to 22,000 men over Kaunitz.

While Charbonnier was busy baking bread, Desjardin's shoeless and badly-clothed men, lacking heavy artillery and with damp gunpowder were making a frontal attack on a well-organized defensive position covered by the repeated charges of the Austrian cavalry.

From cover, the French infantry laid down such an effective fire that the opposing foot soldiers were unable to gain a foothold on the south bank.