Battle of Halmyros

[2] In his landmark[3] 1908 history of Frankish Greece, the medievalist William Miller writes of the Duchy of Athens that "under the dominion of the dukes of the house of de la Roche, trade prospered, manufactures flourished, and the splendours of the Theban court impressed foreigners accustomed to the pomps and pageants of much greater states.

His succession was disputed, but in mid-1309, the High Court (feudal council) of Achaea chose his cousin, the Burgundian noble Walter of Brienne, as successor.

[5] At that time the Greek world was in turmoil owing to the actions of the Catalan Company, a group of mercenaries, veterans of the War of the Sicilian Vespers, originally hired by the Byzantine Empire against the Turks in Asia Minor.

[6][7][8] The last leader of the company, Bernat de Rocafort, had envisaged the restoration of the Kingdom of Thessalonica with himself at its head, and had even entered into negotiations for a marriage alliance with Guy II.

Having just exploited the death of Guy II to repudiate the overlordship of the Dukes of Athens, John turned to Byzantium and the other Greek principality, the Despotate of Epirus, for aid.

Turning back, the Catalans captured the town of Domokos and some thirty other fortresses, and plundered the rich plain of Thessaly, forcing the Greek states to come to terms with Walter.

[11][12] This brought Walter accolades and financial rewards from Pope Clement V, but the Duke now declined to honour his bargain with the Catalans and provide the remaining four months' pay.

Walter picked the best 200 horsemen and 300 Almogavar infantry from the company, paid them their arrears and gave them land so they would remain in his service, while ordering the rest to hand over their conquests and depart.

[11][12][13] The Duke of Athens assembled a large army, comprising his feudatories—among the most prominent were Albert Pallavicini, Margrave of Bodonitsa, Thomas III d'Autremencourt, Lord of Salona and Marshal of Achaea, and the barons of Euboea, Boniface of Verona, George I Ghisi, and John of Maisy—as well as reinforcements sent from the other principalities of Frankish Greece.

The former localization had been long favoured in scholarship; in his standard history of Frankish Greece, William Miller rejected Halmyros on the basis of the topography described by Muntaner,[22] a view that continues to be repeated in more recent works.

[27] A critical piece of evidence was the discovery and publication in 1940 of a 1327 letter by Marino Sanudo, who was a galley captain operating in the North Euboean Gulf on the day of the battle.

Sanudo clearly states that the battle took place at Halmyros ("... fuit bellum ducis Athenarum et comitis Brennensis cum compangna predicta ad Almiro"), and his testimony is generally considered reliable.

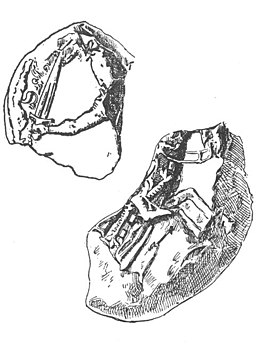

[12] The Catalans chose a naturally strong position, protected by a swamp which, according to Gregoras, they enhanced by digging trenches and inundating them with water diverted from the nearby river.

[42] Impatient for action, according to Muntaner, Walter formed a cavalry line of 200 Frankish knights "with golden spurs", followed by the infantry, and placed himself with his banner in the vanguard.

The Chronicle of the Morea implies that the battle was hard-fought—which, as military historian Kelly DeVries notes, seems to contradict Gregoras—and that the marsh possibly merely reduced the impact of the charge, instead of bogging it down entirely.

Jacoby in particular considers the creation of an artificial marsh to halt the cavalry charge as a possibly invented element in both cases, for the purpose of explaining the surprising defeat of French knights through the use of a "treacherous" trap.

The decimation of the previous feudal aristocracy allowed the Catalans to take possession relatively easily, in many cases marrying the widows and mothers of the very men they had slain in Halmyros.

The Turks of Halil took their share of the booty and headed for Asia Minor, only to be attacked and almost annihilated by a joint Byzantine and Genoese force as they tried to cross the Dardanelles a few months later.

[52][53] Lacking a leader of stature, the Catalan Company turned to their two distinguished captives; they asked Boniface of Verona, whom they knew and respected, to lead them, but after he declined, chose Roger Deslaur instead.

[56][57] In the 1360s, the twin duchies were plagued by internal strife, were locked in a quasi-war with Venice, and increasingly felt the threat of the Ottoman Turks, but another Briennist attempt to launch a campaign against them in 1370–1371 came to naught.