Battle of Hengyang

[11] That same decade, two major railway lines, Wuhan-Guangzhou and Hunan-Guangxi, were built that met in Hengyang, further elevating the strategic importance of the city as a gateway to Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan and Sichuan.

[20] Even before Pearl Harbor, the US government had started quietly helping China by sending the American Volunteer Group (AVG) of aviators and technicians, led by Claire Chennault and popularly known as the Flying Tigers.

[26][27] The total collapse of Chinese armies in the Henan Campaign and rapid fall of Changsha exposed Chiang Kai-shek's perilous state on the home front.

[29] In the meantime, the supreme commanders of China's Ninth, Seventh, and Fourth War Areas, together with high-ranking politician Li Jishen, were also plotting to seize power from Chiang Kai-shek.

In March 1943 when the American 14th Air Force was formally established, the airfield was significantly upgraded for heavy bombers and became a base for the Chinese-American Composite Wing (Provisional), who inherited the nickname "Flying Tigers".

[36] Also active and contributing to the city before the battle were American missionaries and medical staff working at Ren Ji Hospital, run by the Presbyterian church.

[38] The equipment and medicines left behind, particularly sulfa drugs, greatly helped wounded soldiers to recover fast, an indirect factor in Hengyang holding out for so long.

For the rolling hills on the south and south-west, build bunkers linked by trenches, with machine guns deployed on summits flanking saddles so as to create tight killing zones over open grounds.

As a result, the 10th Army received 5.3 million machine gun bullets, 3,200 mortar shells, and 28,000 hand grenades which were going to play an enormous role in the battle.

[65] Reuters journalist Graham Barrow witnessed the evacuation of Hengyang in person: "I was lying asleep by the railway station one night in the rain, then I woke up because there was a train going by.

The mayor organized them into six teams: transporting munitions, fixing damaged defense works, extinguishing fires, carrying stretchers, attending to wounded soldiers, and collecting corpses.

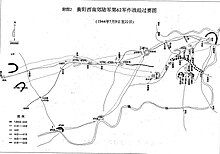

[67] On 20 June 1944, the Japanese commander, Lieutenant General Yokoyama of the 11th Imperial Army, issued the operational deployment for Hengyang: his troops should take the city rapidly, annihilating any Chinese reinforcements on their way.

[78] On the evening of 29 June, after employing flamethrowers and poison gas, Japanese combat troops implemented a novel "shock and awe" tactic: To the sound of bugles, conchs, bull horns, porcelain pipes, gongs, drums, and shouts of "Kill!

[86] On the afternoon of 30 June, Colonel Kurose Heiichi (黑濑平一)of the 133rd Regiment of the Japanese 68th Division ordered preparations to start after sunset for a powerful attack the next morning.

[92] While replenishing its forces and supplies during the week of 3 – 10 July, Japan changed from an overall offensive to nightly attacks at key Chinese positions, mainly in the hilly south and southwest.

From Hengyang Airfield, and despite attacks from the American 14th Air Force, it continuously bombed artillery positions and defense works of the Chinese 10th Army in the southeast, southwest, and west of the city.

"[103] For three days and nights from 11 to 13 July, waves of Japanese troops, a hundred at a time, continuously assaulted 227.7 and 221 heights under cover of air and artillery bombardment.

[111] According to the memoir by Company Commander Yoshiharu Izaki, in taking a small mound south of the city hospital the 133rd Regiment of the 116th Division paid the price of 2,750 lives, leaving only 250 survivors.

[114] Company Commander Xiaoxia Zang's story testifies to a severe shortage of ammunition on the Chinese side: "At dusk 28 July, dozens of enemy soldiers appeared in the gully about a hundred meters away from our position.

Chief of Staff Sun accompanied by G. Zhang and a few other senior officers arrived at the 68th Division command post, where Lieutenant General Tsutsumi Mikio (堤三树男) agreed to have a formal negotiation for ceasefire at nine o'clock the next morning.

[140] From 23 July, Japan managed to break some Chinese radio codes and obtained quite a few important orders and maneuvering instructions from the National Military Council and army headquarters.

[142][143] A review of the Changsha-Hengyang Campaign by the Chinese National Defense admitted: "Our military applied our forces one by one, failing to bring the maximum power into play.

On behalf of Lieutenant General Yokoyama, Takeuchi expressed a high respect for the 10th Army: "Your bravery was not only admired by the Japanese troops here, but also known to our base and even the emperor back in Japan."

Then from September to December, the surviving fighters fleeing from Japanese captivity set off a new upsurge of praise for their lofty heroism, calling General Fang and his soldiers the "spirit of our resistance".

With the help of over sixty surviving battle soldiers, Ge's team worked doggedly and conscientiously for more than four months, digging out skulls and bones, washing them, sprinkling them with perfume, and neatly laying them on the slope of Mt.

Further construction of dormitories, dining halls, and garages in the following two decades resulted in dead soldiers' bones being dug out, scattered, and shipped to wastelands in distant suburbs.

[169] According to the diary by Yongchang Xu (Chinese: 徐永昌), head of the Department of Military Operations, in mid-July 1944, "President Roosevelt telegraphed Chiang Kai-shek, remarking that the Nationalist defeats in Henan and Hunan had damaged China's credibility and suggesting the appointment of General Joseph Stilwell to command Allied forces in China, including those of the Chinese Communists.

Yet, your honorable army could hold out as long as forty-seven days, making us Japanese troops pay a tremendously heavy price, which was indeed an unprecedented undertaking rarely seen in war history during the last eighty years. ...

In 2005, the sixtieth anniversary of the end of World War II, then Party leader Jintao Hu (Chinese: 胡锦涛) was the first to openly admit that Chiang Kai-shek's National Revolutionary Army made crucial contributions on the battlefield.

In the following two decades, the remaining survivors of the battle, who had for half of a century tried not to reveal their service in the Nationalist army, stood up and told combat stories about Hengyang.