Battle of Hernani

The form in which it is generally known today, however, depends on the accounts given by witnesses of the time (Théophile Gautier in particular, who wore a provocative red vest to the Première on 25 February 1830), blending truth and legend in an epic reconstruction intended to make it the founding act of Romanticism in France.

The battle against the aesthetic dogmas of classicism, with its strict rules and rigid hierarchy of theatrical genres, began as early as the 17th century, when Corneille's prefaces attacked the restrictive codifications established by the doctrines of Aristotle, or with the "great comedy" invented by Molière with his plays in five acts and in verse (i.e., in the usual form of tragedy), which added moral criticism to the comic dimension (Tartuffe, The Misanthrope, The School for Wives...).

[2] But it was with Diderot that the idea of a fusion of genres in a new type of play emerged, an idea he was to develop in his Entretiens sur "le Fils naturel" (1757) and his Discours sur la poésie dramatique (1758): considering that classical tragedy and comedy no longer had anything essential to offer contemporary audiences, the philosopher called for the creation of an intermediate genre: drama, which would submit contemporary subjects of reflection to the public.

[8] Guizot's 1821 essay on Shakespeare and, above all, Stendhal's two-part Racine et Shakespeare (1823 and 1825) defended similar ideas, the latter taking the logic of a national dramaturgy even further: If, for Madame de Staël, the alexandrine should disappear from the new dramatic genre, it's because verse banished from the theater "a host of sentiments" and prohibited "saying that one enters or leaves, sleeps or watches, without having to look for a poetic turn of phrase for it",[9] Stendhal rejected it for its inability to capture the French character: "there is nothing less emphatic and more naïve" than this, he explained.

[11] Moreover, Alexandre Dumas, who prided himself on having won "the Valmy of the literary revolution" with his play Henri III, points out that French actors, caught up in their habits, were incapable of moving from the tragic to the comic, as the new writing of Romantic drama demanded.

Their inadequacy was obvious when it came to performing the theater of Hugo, in whom, Dumas explains, "the comic and the tragic touch each other without intermediate nuances, which makes the interpretation of his thought more difficult than if he [...] took the trouble to establish an ascending or descending scale".

[22] In contrast to Stendhal, Hugo advocated the use of versification rather than prose for Romantic drama: the latter was seen as the preserve of a militant, didactic historical theater that was undoubtedly intended to be popular, and which reduced art to the purely utilitarian.

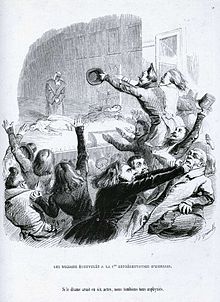

By the second performance, however, the audience, mostly made up of students hostile to the author's liberties with the classical canons, provoked clashes violent enough for grenadiers to storm the auditorium, bayonets fixed.

For the critic of Le Globe, a liberal newspaper, Trente ans marked the end of classicism in the theater, and he lashed out at the proponents of this aesthetic: "Weep for your beloved unities of time and place: here they are once again vividly violated [...] it's all over with your compassed, cold, flat productions.

[40] Among the latter, the main venue for disseminating the Romantic aesthetic was the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin, where most of Dumas's dramas and several of Hugo's plays would be performed, amid vaudevilles and melodramas.

[41] The most prestigious of official performance venues, the Théâtre-Français, had 1,552 seats (worth between 1.80 and 6.60 francs)[42] and was dedicated to promoting and defending the great dramatic repertoire: Racine, Corneille, Molière, sometimes Marivaux, Voltaire and his neo-classical followers: it was explicitly subsidized for this mission.

[45] Nevertheless, despite the quality of their actors, and despite Baron Taylor's recruitment of the set designer Ciceri, who revolutionized the art of theatrical décor,[46] performances at the Théâtre-Français were staged to near-empty houses, as it was notoriously boring to "listen to pompous declamators methodically reciting long speeches", as an editor of the Globe, a newspaper admittedly unfavorable to the neo-classicals,[47] wrote in 1825.

Marion de Lorme, written in one month in June 1829, had been unanimously accepted by the actors of the Théâtre-Français[52] and was therefore to be the first Romantic drama, in verse as recommended in the preface to Cromwell, to be performed on this prestigious stage.

[53] However, despite his reputation as a moderate advocate of the "juste milieu" policy, he refused to overturn the censorship committee's decision: the political situation was delicate, and the staging of a fable that portrayed Louis XIII as a monarch less intelligent than his jester, and dominated by his minister, was likely to inflame the public.

The author of the preface to Cromwell could not afford to take a back seat and leave the limelight to playwrights who, although friends of his, were nonetheless rivals threatening Victor Hugo's dominant position from within his own camp.

[58] Written just as quickly as Marion de Lorme (between 29 August and 24 September 1829),[59] Hernani was read to an audience of some sixty of the author's friends, to great acclaim.

As a result, the censorship commission, still chaired by Brifaut, confined itself to a few remarks, imposing deletions and minor adjustments, notably to passages in which the monarchy was too obviously treated lightly (the line in which Hernani exclaims: "Do you believe, then, that my kings are sacred to me?"

[58] For the rest, the censorship commission's report indicated that, despite the play's abundance of "improprieties of all kinds", it was wiser to allow it to be performed, so that the public could see "how far astray the human mind, freed from all rules and decorum, can go".

[63] Victor Hugo, who showed a much greater interest in the materiality of the performance of his work than his fellow playwrights, was involved in the stage preparation of his plays, choosing the cast himself (when he had the opportunity) and directing rehearsals.

[65] This animal metaphor, while not unheard of in classical theater (it can be found in Racine's Esther and Voltaire's[66] L'Orphelin de la Chine), had in fact taken on a juvenile connotation in the first third of the 19th century, which the actress felt was hardly appropriate for her acting partner.

[76] From among the new generation that made up the "Romantic army" at Hernani's performances would emerge the names Théophile Gautier, Gérard de Nerval, Hector Berlioz, Petrus Borel and others.

That was the age of Bonaparte and Victor Hugo at the time".Gautier's politico-military metaphor was neither arbitrary nor unprecedented: the parallel between the theater and the City in their struggle against the systems and constraints of the established order, summed up in 1825 in Le Globe critic Ludovic Vitet's lapidary formula ("le goût en France attend son 14 juillet ")[80] was one of the truisms of a generation of literati and artists who looked to the political revolution as their strategic model,[81] and who readily used military language: "The breach is open, we shall pass",[82] Hugo had said after the success of Dumas's Henri III.

[86] The theater's employees did their part to help the forces of law and order, pelting the Romantics with garbage from the balconies (legend has it that Balzac was hit in the face with a cabbage core).

Don Gomez's long tirade in the gallery of portraits of his ancestors (Act III, scene VI), which had been eagerly awaited, had been cut in half, so that Hugo's opponents, taken by surprise, had no time to switch from murmurs to whistles.

[91] The next two performances were just as successful: it had to be said that Baron Taylor had asked Hugo to bring back his "claque" (who would no longer have to spend the afternoon in the theater), and that no less than six hundred students formed the troupe of the writer's supporters.

[98] Don Gomez was renamed Dégommé, dona Sol Quasifol or Parasol...[99] Four parodic plays and three pamphlets (the ironic tone of one of which, directed against "literary cafarderie", shows that it was actually written in Hugo's entourage)[100] were launched in the months following the first performance of the drama.

[105] Note, however, the opinion of Sainte-Beuve: "The Romantic question is carried, by the mere fact of Hernani, a hundred leagues forward, and all the theories of the contradictors are upset; they have to rebuild others afresh, which Hugo's next play will further destroy".

[111] A reviewer for the legitimist journal La Quotidienne was quick to point this out in 1838, on the occasion of another scandal, this time caused by Ruy Blas:[112] "Let Mr. Hugo make no mistake, his plays find more opposition to his political system than to his dramatic one; they are less resented for scorning Aristotle than for insulting kings [...] and he will always be more easily forgiven for imitating Shakespeare than Cromwell".The discrepancy between the reality of the events surrounding Hernani's performances and the image that has remained of them is palpable: posterity has remembered Mademoiselle Mars's unpronounceable "lion", Balzac's cabbage core, the blows and insults exchanged between the "classics" and the "romantics", the "stolen staircase" on which the classic verse stumbled, Gautier's red vest, and so on, It's a mixture of truth and fiction, which reduces to the date of 25 February 1830 events that took place over several months, and forgets that the first performance of Hugo's drama was, almost without a fight, a triumph for the leader of the Romantic aesthetic.

[113] The essential elements of this "myth of a cultural Grand Soir"[114] were established as early as the nineteenth century by direct witnesses to the events: Alexandre Dumas, Adèle Hugo and, above all, Théophile Gautier, a relentless hernianist.

We had the honor of being enrolled in those young bands who fought for the ideal, poetry and the freedom of art, with an enthusiasm, bravery and devotion no longer known today".The military metaphor and the parallel with Bonaparte continued in the rest of the story, which also gave pride of place to the picturesque (an entire chapter of the book is devoted to the "red vest"), and above all condensed into a single memorable evening events borrowed from different representations, in a largely idealized evocation of events that would make a lasting contribution to fixing the date of 25 February 1830 as the founding act of Romanticism in France.