Battle of Iquique

In 1879, the Bolivian government threatened to confiscate and sell the Antofagasta Nitrate & Railway Company, a mining enterprise with Chilean and British investors.

This action prompted Bolivian President Hilarión Daza to declare war on Chile and forced Peru to honor a secret 1873 treaty with Bolivia.

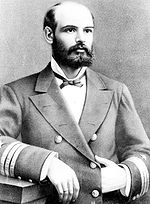

However, two ironclad ships of the Peruvian Navy, the monitor Huáscar and the armored frigate Independencia, commanded by Rear Admiral Miguel Grau and Captain Juan Guillermo More, respectively, steamed south from Callao undetected.

At the same time, Peruvian admiral Grau rallied his crew: "Crewmembers and Sailors of the Huáscar, Iquique is in sight, there are our afflicted fellow countrymen from Tarapacá, and also the enemy, still unpunished.

Remember how our forces distinguished in Junin, the 2nd of May, Abtao, Ayachucho, and other battlefields, to win us our glorious and dignified independence, and our consecrated and brilliant laurels of freedom.

At 8:25 a.m., a second round of shots was fired, and Huáscar's projectile struck Esmeralda's starboard side, penetrating the ship and resulting in the death of Surgeon Videla, the beheading of his assistant, and the fatal injury of another sailor.

Prat swiftly positioned the ship near the coastline, approximately 200 meters (660 ft) away, forcing Huáscar to fire in a parabolic trajectory to avoid hitting the Peruvian village where onlookers had gathered to witness the battle.

General Buendía, the commander of the Peruvian garrison in Iquique, positioned artillery on the beach and dispatched a messenger in a fast rowing boat to warn Huáscar that Esmeralda was loaded with torpedoes.

Grau halted Huáscar approximately 600 meters (660 yards) away from Esmeralda and began firing the 300-pound cannons, but due to the Peruvian sailors' lack of experience in handling the monitor's Coles turret, they failed to hit their target for an hour and a half.

The battle continued, with the crew of Huáscar facing difficulties in targeting the Chilean corvette as, from their perspective, their own countrymen and the Peruvian port lay behind Esmeralda.

Prat attempted to evade the collision by maneuvering the ship forward and closing a port, managing to avoid further damage when the blow struck near the mizzen mast.

Lieutenant Luis Uribe Orrego, acting as the ship's captain at that point, called for an official meeting on Esmeralda and decided not to surrender to the Peruvian Navy.

During this time, a sailor climbed the mizzen mast to secure the Chilean national flag, ensuring that the crew would remember Prat's words before the battle.

Grau soon received information that the attempted truce had failed once again and decided to ram Esmeralda for a second time, charging at full speed towards its starboard side.

Huáscar once again unleashed gunfire at close range, resulting in casualties among the crew, including engineers and firemen who had surfaced on deck, and destroying the officers' mess room, which also served as the ship's clinic.

Emulating Prat's actions during the initial ramming, Sublieutenant Ignacio Serrano and eleven other men armed with machetes and rifles boarded Huáscar but were unsuccessful and fell victim to the Gatling guns and the monitor's crew.

Grau quickly ordered his rescue and had Serrano taken to the infirmary in a state of shock, where he was placed alongside the mortally wounded Petty Officer Aldea.

It was midday, precisely 12:10 p.m., and Grau realized that many Chilean sailors and marines (reports indicate that 57 survived) were struggling to avoid being pulled down by the sinking ship, while their captain had perished hours earlier.

Grau promptly joined the engagement and arrived at 3:10 p.m., finding Independencia stranded in shallow water with 20 surviving crew members, including More, as the rest had landed on the shore in boats.

On Saturday, May 24, the Chilean Navy General Staff and Naval High Command held a special meeting and sent reports of the battles to the War Department in Santiago.

Over time, Prat's significance became deeply ingrained in the Chilean collective consciousness, to the extent that newspapers began using the term "Pratiotism" as a substitute for "Patriotism."