Battle of the Camel

Ali frequently accused the third caliph Uthman of deviating from the Quran and the Sunna,[7][8][9] and he was joined in this criticism by most of the senior companions, including Talha and Zubayr.

Giorgio Levi della Vida (d. 1967) is unsure, while Wilferd Madelung strongly rejects the accusation, saying that it "stretches the imagination" in the absence of any evidence.

[66][67] While he did not condone the assassination,[68] Ali probably held Uthman responsible through his injustice for the protests which led to his death,[66][69] a view for which Ismail Poonawala cites Waq'at Siffin.

[75] Quoting the Shia al-Ya'qubi (d. 897-8) and Ibn A'tham al-Kufi, Ayoub suggests that a mob from various tribes murdered Uthman and that Ali could have not punished them without risking widespread tribal conflict, even if he could identify them.

[76] Here, Farhad Daftary and John Kelsay say that the actual murderers soon fled (Medina) after the assassination,[20][77] a view for which Jafri cites al-Tabari.

[96] Talha and Zubayr, both companions of Muhammad with ambitions for the high office,[97][98] offered their pledges to Ali but later broke them,[99][8][100] after leaving Medina on the pretext of performing the umra (lesser pilgrimage).

[102] Alternatively, Hamid Mavani refers to a letter in Nahj al-balagha where Ali rebukes Talha and Zubayr before the Battle of the Camel for breaking their oaths after voluntarily offering them.

[107] Some authors represent Aisha as an unwilling political victim in this saga, like one by al-Ya'qubi,[104] and some say that she desired peace,[108] while others emphasize her central role in mobilizing the rebel party against Ali,[59][106] in favor of her close relatives, namely, Talha and Zubayr.

[118] Ali was also vocal about the divine and exclusive right of Muhammad's kin to succeed him,[119][120] which similarly jeopardized the future ambitions of other Qurayshites for leadership.

[124] Veccia Vaglieri suggests that the triumvirate of Talha, Zubayr, and Aisha had opposed Uthman with plans for "moderate" changes after him which did not materialize under Ali.

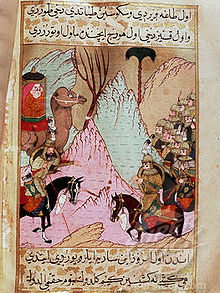

[126] In October 656,[59] led by Aisha, Talha and Zubayr, six to nine hundred Meccan rebels marched on the garrison city of Basra,[109] some 1300 kilometers away from Hejaz, where they were unable to muster much support.

[54] In Basra, Aisha wrote letters to incite against Ali, addressed to Kufans and their governor, to Medinans, and to Hafsa bint Umar, another widow of Muhammad.

[138] Ali then sent his son Hasan and Ammar ibn Yasir or al-Ashtar himself to rally the support of the Kufans,[2][140] who met the caliph outside of the town with an army of six to seven thousand men.

[2][31] After Ali appealed to the opposite camp, large numbers defected to his side, possibly tipping the numerical strength in his favor.

[144][145] This reminder greatly disturbed Zubayr, writes al-Tabari, but he was persuaded to continue the campaign, contrary to the reports that he left before the battle.

[146] The details of the negotiations are not reliable for Madelung but he does conclude that the talks broke the resolve of Zubayr, who might have realized his small chances for the caliphate and perhaps the immorality of his bloody rebellion.

[53] Veccia Vaglieri similarly says that the "extremists" in Ali's camp provoked the war,[7] while Madelung argues that the account of Sayf to this effect is fictitious and not backed by the other sources.

[54] Possibly in a last-ditch effort to avoid war, early sources widely report that the caliph ordered one of his men to raise a copy of the Quran between the battle lines and appeal to its contents.

[90] Nevertheless, the sources are mostly silent about the tactical developments, but Veccia Vaglieri suggests that the battle consisted of a series of duels and encounters, as this was the Arab custom at the time.

[160][161][159] Madelung similarly believes that the murder of Talha was premeditated and postponed by Marwan long enough for him to be confident that he would not face any retribution from a victorious Aisha.

[90] Zubayr, an experienced fighter, left shortly after the battle began,[153][54] possibly without having fought at all,[153] or after Talha was killed,[152][90] or after single combat with Ammar, according to al-Tabari.

[162][54] Apparently al-Ahnaf ibn Qays, a pro-Ali chief of the Banu Sa'd, who had remained on the sidelines of the battle, learned about the desertion.

[163] Some of his men then followed and killed Zubayr,[153][54] either to gratify Ali, or more likely for his dishonorable act of leaving other Muslims behind in a civil war he had ignited,[162] as suggested by al-Ya'qubi, Ayoub, and Madelung.

[90] When the news of his death reached Ali, he commented that Zubayr had many times fought valiantly in front of Muhammad but that he had come to an evil end.

[163] The deaths of Talha and Zubayr likely sealed the fate of the battle,[54][157][90] despite the intense fighting that continued possibly for hours around Aisha's camel.

[54] Still, both Ali and his representative Ibn Abbas reprimanded Aisha as they saw her responsible for the loss of life and for leaving her home in violation of the Quran's instructions for Muhammad's widows.

[175] He cites a tradition related by Kabsha bint Ka'b ibn Malik, in which Aisha praises Uthman and regrets that she incited revolt against him (but not against Ali).

[176] Ali announced a public pardon after the battle,[173] setting free the war prisoners and prohibiting the enslavement of their women and children.

[54] The discontented soldiers questioned why they were not allowed to take enemy's possessions and enslave their women and children when shedding their blood was considered lawful.

[14] Kennedy similarly highlights the strategic disadvantages of Medina, saying that it was far from population centers of Iraq and Syria, and heavily depended on grain shipments from Egypt.