Battle of Jumonville Glen

A company of provincial troops from Virginia under the command of Lieutenant Colonel George Washington, and a small number of Mingo warriors led by the chieftain Tanacharison (also known as the "Half King"), ambushed a force of 35 French Canadians under the command of Joseph Coulon de Jumonville.

Washington was alerted to Jumonville's presence by Tanacharison, and they joined forces to ambush the French Canadian camp.

Despite good Franco-Indian relations, British traders had become highly successful in convincing the Indians to trade with them in preference to the Canadians, and the planned large-scale advance was not well received by all.

[13] The Governor also issued a captain's commission to Ohio Company employee William Trent, with instructions to raise a small force and immediately begin construction of the fort.

Dinwiddie issued these instructions on his own authority, without even asking for funding from the Virginia House of Burgesses until after the fact.

[14] Trent's company arrived on site in February 1754, and began construction of a storehouse and stockade with the assistance of Tanacharison and the Mingos.

[18] In March 1754, Dinwiddie ordered Washington back to the frontier with instructions to "act on the [defensive], but in Case any Attempts are made to obstruct the Works or interrupt our [settlements] by any Persons whatsoever, You are to restrain all such Offenders, & in Case of resistance to make Prisoners of or kill & destroy them".

[19] Historian Fred Anderson describes Dinwiddie's instructions, which were issued without the knowledge or direction of the British government in London, as "an invitation to start a war".

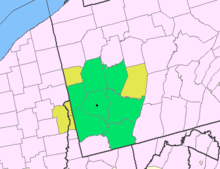

He reached a place known as the Great Meadows (now in Fayette County, Pennsylvania), about 37 miles (60 km) south of the forks, began to construct a small fort and awaited further news or instructions.

[2] On May 27, Washington was informed by Christopher Gist, a settler who had accompanied him on the 1753 expedition, that a French Canadian party numbering about 50 was in the area.

[25] According to French Canadian records, most of the dead were French Canadians: Desroussel and Caron from Québec City, Charles Bois from Pointe-Claire, Jérôme from La Prairie, L'Enfant from Montréal, Paris from Mille-Isles, Languedoc and Martin from Boucherville, and LaBatterie from Trois-Rivières.

[26] Washington's accounts of the battle exist in several versions; they are consistent with one another, but the details are compressed, according to historian Fred Anderson, with the intent to obscure post-battle atrocities.

Alerted by a noise, one of the Frenchmen Shaw's narrative is substantially correct on a number of other details, including the size and composition of both forces.

That [Tanacharison], a savage, came up to [the wounded Jumonville] and had said, "Tu n'es pas encore mort, mon père!"

[1][4] Washington wrote a letter to his brother after the battle in which he said "I can with truth assure you, I heard bullets whistle and believe me, there was something charming in the sound.

[40][41] An exception was Michel Pépin, called "La Force," a skilled interpreter with whom Washington was previously acquainted.

When news of the two battles reached England in August, the government of the Duke of Newcastle, after several months of negotiations, sent an army expedition the following year to dislodge the French.

[46] Word of the British military plans had leaked to France well before Braddock's departure for North America, and King Louis XV dispatched a much larger body of troops to Canada in 1755.

[48] Military actions continued on soil and at sea in North America until France and Great Britain declared war on each other in spring 1756.

[49] Because of the inconsistent nature of the record of the action, contemporary and historical coverage of it has been easily colored by preferences for one account over another.

Entitled "Mémoire contenant le précis des faits, avec leurs pièces justificatives, pour servir de réponse aux 'Observations' envoyées par les Ministres d'Angleterre, dans les cours de l'Europe", a copy was intercepted in 1756, translated, and published as "A memorial containing a summary view of facts, with their authorities, in answer to observations sent by the English ministry to the courts of Europe".

Jumonville's orders included specific instructions to notify Contrecœur if the summons was read so that additional forces might be sent if needed.