Battle of Kasserine Pass

The initial handful of American battalions suffered many casualties and were successively pushed back over 50 miles (80 km) from their original positions west of Faïd Pass, until they met an advancing brigade of the U.S. 1st Armored Division.

[9][10][11][12] As a result of lessons learned in this battle, the U.S. Army instituted sweeping changes in unit organization and tactics, and replaced some commanders[7] and some types of equipment.

[16] Elements of the 5th Panzer Army, headed by General Hans-Jürgen von Arnim, reached the Allied positions on the eastern foot of the Atlas Mountains on January 30.

[citation needed] Rommel did not consider the Eighth Army a serious threat because, until Tripoli was open, Montgomery could maintain only a small force in south Tunisia.

[19] Rommel made a proposal in early February to Comando Supremo (Italian High Command in Rome) to attack with two battlegroups, including detachments from the 5th Panzer Army, toward two U.S. supply bases just to the west of the western arm of the mountains in Algeria.

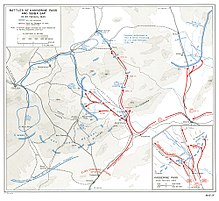

Arnim objected and the attack was delayed for a week until agreement was reached to mount Operation Frühlingswind, a thrust by the 5th Panzer Army through the U.S. communications and supply center of Sidi Bou Zid.

[20] On February 14 the 10th and 21st Panzer divisions began the Battle of Sidi Bou Zid, about 10 mi (16 km) west of Faïd, in the interior plain of the Atlas Mountains.

The Kampfgruppe von Broich, the battlegroup released by Arnim from 10th Panzer Division, was ordered to concentrate at Sbeitla, where it would be ready to exploit success in either pass.

Furthest west was Task Force Bowen (consisting of the 3rd Battalion of the 26th Regimental Combat Team), blocking the track from Feriana towards Tebessa.

[33] Rommel decided to commit his units from the 10th Panzer to the Kasserine Pass the next morning in a coordinated attack with the Afrika Korps Assault Group, which was to be joined by elements of the Italian 131st Armored Division Centauro.

[28] British reinforcements from the 26th Armoured Brigade had been assembling at Thala and Brigadier Charles Dunphie, making forward reconnaissance, decided to intervene.

The First Army headquarters restricted him to sending Gore Force, a small combined-arms group of a company of infantry, a squadron of 11 tanks, an artillery battery and an anti-tank troop.

[34] During the night, the American positions on the two shoulders overlooking the pass were overrun and at 8:30 am German panzer grenadiers and Italian Bersaglieri resumed the attack.

The Italian regiment was complimented by General Bülowius, commander of the DAK Assault Group, who cited their action as the instrumental event of the Axis victory.

[36][37] The U.S. survivors made a disorganized retreat up the western exit from the pass to Djebel el Hamra, where Combat Command B of the 1st Armored Division was arriving.

Plans made by both sides were upset by the battle, and the Axis forces (5th Bersaglieri, a Semovente group from Centauro and 15 Panzer) launched another assault on the U.S. position on the morning of February 22 toward Bou Chebka Pass.

Although the American defenders were pressed hard the line held and, by mid-afternoon, the U.S. infantry and tanks launched a counterattack that broke the combined German and Italian force.

[39] Rommel had stayed with the main group of the 10th Panzer Division on the route toward Thala, where the 26th Armoured Brigade and remnants of the U.S. 26th Infantry Regiment had dug in on ridges.

[40] The divisional artillery (48 guns) of the 9th Infantry Division and anti-tank platoons, that had moved from Morocco on February 17, 800 mi (1,300 km) west, dug in that night.

[43] On the morning of February 22 an intense artillery barrage from the massed Allied guns forestalled the resumption of the 10th Panzer Division attack, destroying armor and vehicles and disrupting communications.

[43] Overextended and with supplies dwindling, pinned down by the Allied artillery in the pass in front of Thala and now facing U.S. counterattacks along the Hatab River, Rommel realized his strength was spent.

At Sbiba, along the Hatab River and now at Thala, the efforts of the German and Italian forces had failed to make a decisive break in the Allied line.

With little prospect of further success, Rommel judged that it would be wiser to break off to concentrate in South Tunisia and strike a blow at the Eighth Army, catching them off balance while still assembling its forces.

Rommel was adamant; Kesselring finally agreed and formal orders from the Comando Supremo in Rome were issued that evening calling off the offensive and directing all Axis units to return to their start positions.

[48] Rommel had hoped to take advantage of the inexperience of the new Allied commanders but was opposed by Arnim who, wanting to conserve strength in his sector, ignored Kesselring's orders and withheld the attached heavy tank unit of 10th Panzer.

[7] Training programs at home had contributed to U.S. Army units in North Africa being saddled with disgraced commanders who had failed in battle and were reluctant to advocate radical changes.

[55] Eisenhower found through Major General Omar Bradley and others, that Fredendall's subordinates had lost confidence in him and Alexander told U.S. commanders, "I'm sure you must have better men than that".

)[57] On 6 March, Major General George Patton was temporarily removed from planning for the Allied invasion of Sicily to command the II Corps.

During the advance from Gafsa, Alexander, the 18th Army Group commander, had given detailed orders to Patton, afterwards changing II Corps' mission several times.

From then on, Patton simply ignored those parts of mission orders he considered ill-advised on grounds of military expediency and/or a rapidly evolving tactical situation.