Battle of Lepanto

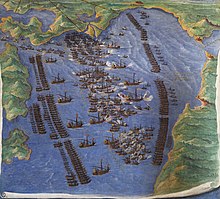

The Ottoman fleet consisted of 222 galleys and 56 galliots and was led by Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, Mahomet Sirocco and Occhiali.

In the history of naval warfare, Lepanto marks the last major engagement in the Western world to be fought almost entirely between rowing vessels,[10] namely the galleys and galleasses which were the direct descendants of ancient trireme warships.

Over the following decades, the increasing importance of the galleon and the line of battle tactic would displace the galley as the major warship of its era, marking the beginning of the "Age of Sail".

However, the Ottoman commander, Lala Kara Mustafa Pasha had lost some 50,000 men in the siege and broke his word, imprisoning the Venetians, and had Marco Antonio Bragadin flayed alive.

[21] The banner for the fleet, blessed by the Pope, reached the Kingdom of Naples (then ruled by Philip II of Spain) on 14 August 1571, where it was solemnly consigned to John of Austria.

John of Austria, half-brother of Philip II of Spain, was named by Pope Pius V as overall commander of the fleet and led the centre division, with his principal deputies and counselors being the Roman Marcantonio Colonna and the Venetian Sebastiano Venier; the wings were commanded by the Venetian Agostino Barbarigo and the Genoese Gianandrea Doria.

[35] The historian George Finlay estimated that over 25,000 Greeks fought on the side of the Holy League during the battle (both as soldiers and sailors/oarsmen) and stated that their numbers "far exceeded that of the combatants of any other nation engaged".

[38] The Venetian oarsmen were mainly free citizens and able to bear arms, adding to the fighting power of their ships, whereas convicts were used to row many of the galleys in other Holy League squadrons.

[13] The Christian fleet started from Messina on 16 September, crossing the Adriatic and creeping along the coast, arriving at the group of rocky islets lying just north of the opening of the Gulf of Corinth on 6 October.

[42] Despite bad weather, the Christian ships sailed south and, on 6 October, reached the port of Sami, Cephalonia (then also called Val d'Alessandria), where they remained for a while.

[47] Meanwhile, the centres clashed with such force that Ali Pasha's galley drove into the Real as far as the fourth rowing bench, and hand-to-hand fighting commenced around the two flagships, between the Spanish Tercio infantry and the Turkish janissaries.

[48] A flag taken at Lepanto by the Knights of Saint Stephen, said to be the standard of the Turkish commander, is still on display, in the Church of the seat of the Order in Pisa.

Ali attacked a group of some fifteen galleys around the flagship of the Knights of Malta, threatening to break into the Christian centre and still turn the tide of the battle.

It is said that at some point the Janissaries ran out of weapons and started throwing oranges and lemons at their Christian adversaries, leading to awkward scenes of laughter among the general misery of battle.

The Christian victory at Lepanto confirmed the de facto division of the Mediterranean, with the eastern half under firm Ottoman control and the western under the Spanish Crown and their Italian allies.

[54] Historian Paul K. Davis sums up the importance of Lepanto this way: "This Turkish defeat stopped Ottomans' expansion into the Mediterranean, thus maintaining Western dominance, and confidence grew in the West that Turks, previously unstoppable, could be beaten.

[57] Sultan Selim II's Chief Minister, the Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, even boasted to the Venetian emissary Marcantonio Barbaro that the Christian triumph at Lepanto caused no lasting harm to the Ottoman Empire, while the capture of Cyprus by the Ottomans in the same year was a significant blow, saying that: You come to see how we bear our misfortune.

Andrea Doria had kept a copy of the miraculous image of Our Lady of Guadalupe given to him by King Philip II of Spain in his ship's state room.

[69] Giovanni Pietro Contarini's History of the Events, which occurred from the Beginning of the War Brought against the Venetians by Selim the Ottoman, to the Day of the Great and Victorious Battle against the Turks was published in 1572, a few months after Lepanto.

It is also the only full historical account by an immediate commentator, blending his straightforward narrative with keen and consistent reflections on the political philosophy of conflict in the context of the Ottoman–Catholic confrontation in the early modern Mediterranean.

[71] Numerous paintings were commissioned, including one in the Doge's Palace, Venice, by Andrea Vicentino on the walls of the Sala dello Scrutinio, which replaced Tintoretto's Victory of Lepanto, destroyed by fire in 1577.

Titian painted the battle in the background of an allegorical work showing Philip II of Spain holding his infant son, Don Fernando, his male heir born shortly after the victory, on 4 December 1571.

[72] The Allegory of the Battle of Lepanto (c. 1572, oil on canvas, 169 x 137 cm, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice) is a painting by Paolo Veronese.

[citation needed] A painting by Wenceslas Cobergher, dated to the end of the 16th century, now in San Domenico Maggiore, shows what is interpreted as a victory procession in Rome on the return of admiral Colonna.

On the stairs of Saint Peter's Basilica, Pius V is visible in front of a kneeling figure, identified as Marcantonio Colonna returning the standard of the Holy League to the pope.

Though these longer works have, in the words of a later critic, "not unjustly been consigned to that oblivion which few epics have escaped", there was also a Spanish ballad which retained its popularity and was translated into English by Thomas Rodd in 1818.

Written in fourteeners about 1585, its thousand lines were ultimately collected in His Maiesties Poeticall Exercises at Vacant Houres (1591),[77] then published separately in 1603 after James had become king of England too.

There were also translations in other languages, including into Dutch as Den Slach van Lepanten (1593) by Abraham van der Myl,[78] La Lepanthe, the French version by Du Bartas, accompanied James' 1591 edition; a Latin version, the Naupactiados Metaphrasis by Thomas Murray (1564–1623), followed a year after James' 1603 publication.

At the start of the 20th century too, Emilio Salgari devoted his historical novel, Il Leone di Damasco ("The Lion of Damascus", 1910), to the Battle of Lepanto, which was eventually to be adapted to film by Corrado D'Errico in 1942.

[82] In 1942 as well, English author Elizabeth Goudge has a character in her war-time novel, The Castle on the Hill (1942), recall the leading role of John of Austria in the battle and the presence of Cervantes there.