Battles of Lexington and Concord

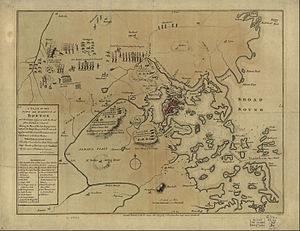

[9] The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County in the colonial-era Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Menotomy (present-day Arlington), and Cambridge.

The colonial assembly responded by forming a Patriot provisional government known as the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and calling for local militias to train for possible hostilities.

About 700 British Army regulars in Boston, under Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith, were given secret orders to capture and destroy Colonial military supplies reportedly stored by the Massachusetts militia at Concord.

Under the laws of each New England colony, all towns were obligated to form militia companies composed of all males 16 years of age and older (there were exemptions for some categories) and to ensure that the members were properly armed.

[14] A February 1775 address to King George III, by both houses of Parliament, declared that a state of rebellion existed: We ... find that a part of your Majesty' s subjects, in the Province of the Massachusetts Bay, have proceeded so far to resist the authority of the supreme Legislature, that a rebellion at this time actually exists within the said Province; and we see, with the utmost concern, that they have been countenanced and encouraged by unlawful combinations and engagements entered into by your Majesty's subjects in several of the other Colonies, to the injury and oppression of many of their innocent fellow-subjects, resident within the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the rest of your Majesty' s Dominions ... We ... shall ... pay attention and regard to any real grievances ... laid before us; and whenever any of the Colonies shall make a proper application to us, we shall be ready to afford them every just and reasonable indulgence.

[17] On the morning of April 18, Gage ordered a mounted patrol of about 20 men under the command of Major Mitchell of the 5th Regiment of Foot into the surrounding country to intercept messengers who might be out on horseback.

A well-known story alleges that after nightfall one farmer, Josiah Nelson, mistook the British patrol for the colonists and asked them, "Have you heard anything about when the regulars are coming out?"

[20] On March 30, 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress issued the following resolution: Whenever the army under command of General Gage, or any part thereof to the number of five hundred, shall march out of the town of Boston, with artillery and baggage, it ought to be deemed a design to carry into execution by force the late acts of Parliament, the attempting of which, by the resolve of the late honourable Continental Congress, ought to be opposed; and therefore the military force of the Province ought to be assembled, and an army of observation immediately formed, to act solely on the defensive so long as it can be justified on the principles of reason and self-preservation.

After a large contingent of regulars alarmed the countryside by an expedition from Boston to Watertown on March 30, The Pennsylvania Journal, a newspaper in Philadelphia, reported, "It was supposed they were going to Concord, where the Provincial Congress is now sitting.

[27] The colonists were also aware that April 19 would be the date of the expedition, despite Gage's efforts to keep the details hidden from all the British rank and file and even from the officers who would command the mission.

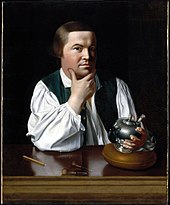

[28] Between 9 and 10 pm on the night of April 18, 1775, Joseph Warren told Revere and William Dawes that the British troops were about to embark in boats from Boston bound for Cambridge and the road to Lexington and Concord.

He then traveled the northern water route, crossing the mouth of the Charles River by rowboat, slipping past the British warship HMS Somerset at anchor.

[53] A British officer (probably Pitcairn, but accounts are uncertain, as it may also have been Lieutenant William Sutherland) then rode forward, waving his sword, and called out for the assembled militia to disperse, and may also have ordered them to "lay down your arms, you damned rebels!

[72] Colonel Barrett's troops, upon seeing smoke rising from the village square as the British burned cannon carriages, and seeing only a few light infantry companies directly below them, decided to march back toward the town from their vantage point on Punkatasset Hill to a lower, closer flat hilltop about 300 yards (274 m) from the North Bridge.

"[87] During a tense standoff lasting about 10 minutes, a mentally ill local man named Elias Brown wandered through both sides selling hard cider.

[88] Lieutenant Colonel Smith, concerned about the safety of his men, sent flankers to follow a ridge and protect his forces from the roughly 1,000 colonials now in the field as the British marched east out of Concord.

[85] In their accounts afterward, British officers and soldiers alike noted their frustration that the colonial militiamen fired at them from behind trees and stone walls, rather than confronting them in large, linear formations in the style of European warfare.

[101] This image of the individual colonial farmer, musket in hand and fighting under his own command, has also been fostered in American myth: "Chasing the red-coats down the lane / Then crossing the fields to emerge again / Under the trees at the turn of the road, / And only pausing to fire and load.

Reflecting on the British experience that day, Earl Percy understood the significance of the American tactics: During the whole affair the Rebels attacked us in a very scattered, irregular manner, but with perseverance & resolution, nor did they ever dare to form into any regular body.

[110] Percy assumed control of the combined forces of about 1,700 men and let them rest, eat, drink, and have their wounds tended at field headquarters (Munroe Tavern) before resuming the march.

Based on the word of Pitcairn and other wounded officers from Smith's command, Percy had learned that the Minutemen were using stone walls, trees and buildings in these more thickly settled towns closer to Boston to hide behind and shoot at the column.

Fresh militia arrived in close array instead of in a scattered formation, and Percy used his two artillery pieces and flankers at a crossroads called Watson's Corner to inflict heavy damage on them.

Some accused the commander of this force, Colonel Timothy Pickering, of permitting the troops to pass because he still hoped to avoid war by preventing a total defeat of the regulars.

[129] Thomas Paine in Philadelphia had previously thought of the argument between the colonies and the Home Country as "a kind of law-suit", but after news of the battle reached him, he "rejected the hardened, sullen-tempered Pharaoh of England forever".

[130] George Washington received the news at Mount Vernon and wrote to a friend, "the once-happy and peaceful plains of America are either to be drenched in blood or inhabited by slaves.

The story of the wounded British soldier at the North Bridge, hors de combat, struck down on the head by a Minuteman using a hatchet, the purported "scalping", was strongly suppressed.

[136] A minor controversial interpretation holds that the Battle of Point Pleasant on October 10, 1774, in what is now West Virginia was the initial military engagement of the Revolutionary War, and a 1908 United States Senate resolution designated it as such.

In 1961, left-wing novelist Howard Fast published April Morning, an account of the battle from a fictional 15-year-old's perspective, and reading of the book has been frequently assigned in American secondary schools.

The Town of Concord invited 700 prominent U.S. citizens and leaders from the worlds of government, the military, the diplomatic corps, the arts, sciences, and humanities to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the battles.

On April 19, 1975, as a crowd estimated at 110,000 gathered to view a parade and celebrate the Bicentennial in Concord, President Gerald Ford delivered a major speech near the North Bridge, which was televised to the nation.