Battle of the Little Bighorn

[12][13][14] The fight was an overwhelming victory for the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho, who were led by several major war leaders, including Crazy Horse and Chief Gall, and had been inspired by the visions of Sitting Bull (Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake).

[29] During a Sun Dance around June 5, 1876, on Rosebud Creek in Montana, Sitting Bull, the spiritual leader of the Hunkpapa Lakota, reportedly had a vision of "soldiers falling into his camp like grasshoppers from the sky.

A significant portion of the regiment had previously served 4½ years at Fort Riley, in Kansas, during which time it fought one major engagement and numerous skirmishes, experiencing casualties of 36 killed and 27 wounded.

[33] By the time of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, half of the 7th Cavalry's companies had just returned from 18 months of constabulary duty in the Deep South, having been recalled to Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory to reassemble the regiment for the campaign.

Surprised and according to some accounts astonished by the unusually large numbers of Native Americans, Crook held the field at the end of the battle but felt compelled by his losses to pull back, regroup, and wait for reinforcements.

[43] With an impending sense of doom, the Crow scout Half Yellow Face prophetically warned Custer (speaking through the interpreter Mitch Bouyer), "You and I are going home today by a road we do not know.

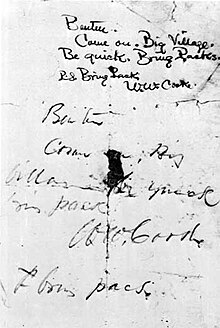

As Custer and nearly 210 troopers and scouts began their final approach to the massive Indian village located in the Little Bighorn River Valley, Martino was dispatched with an urgent note for reinforcements and ammunition.

Later, looking from a hill 2+1⁄2 miles (4 km) away after parting with Reno's command, Custer could observe only women preparing for the day, and young boys taking thousands of horses out to graze south of the village.

[49] Custer's field strategy was designed to engage non-combatants at the encampments on the Little Bighorn to capture women, children, and the elderly or disabled[50]: 297 to serve as hostages to convince the warriors to surrender and comply with federal orders to relocate.

[52] Author Evan S. Connell observed that if Custer could occupy the village before widespread resistance developed, the Sioux and Cheyenne warriors "would be obliged to surrender, because if they started to fight, they would be endangering their families.

"[50]: 312 [53] In Custer's book My Life on the Plains, published two years before the Battle of the Little Bighorn, he asserted: Indians contemplating a battle, either offensive or defensive, are always anxious to have their women and children removed from all danger ... For this reason I decided to locate our [military] camp as close as convenient to [Chief Black Kettle's Cheyenne] village, knowing that the close proximity of their women and children, and their necessary exposure in case of conflict, would operate as a powerful argument in favor of peace, when the question of peace or war came to be discussed.

[55]: 379 The Sioux and Cheyenne fighters were acutely aware of the danger posed by the military engagement of non-combatants and that "even a semblance of an attack on the women and children" would draw the warriors back to the village, according to historian John S.

Fox, James Donovan, and others, Custer proceeded with a wing of his battalion (Yates' E and F companies) north and opposite the Cheyenne circle at that crossing,[50]: 176–77 which provided "access to the [women and children] fugitives.

"[50]: 306 Yates's force "posed an immediate threat to fugitive Indian families..." gathering at the north end of the huge encampment;[50]: 299 he then persisted in his efforts to "seize women and children" even as hundreds of warriors were massing around Keogh's wing on the bluffs.

As Reno's men fired into the village and by some accounts killed several wives and children of the Sioux chief Gall (in Lakota, Phizí), the mounted warriors began streaming out to meet the attack.

This practice had become standard during the last year of the American Civil War, as Union and Confederate troops used knives, eating utensils, mess plates and pans to dig effective battlefield fortifications.

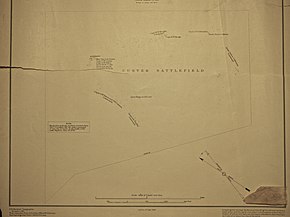

From a distance, as well as looking though his spyglass, Weir witnessed many Indians on horseback and on foot shooting at items on the ground, perhaps killing wounded soldiers and firing at dead bodies on the "Last Stand Hill" at the northern end of the Custer battlefield.

[citation needed] The destruction of Keogh's battalion may have begun with the collapse of L, I and C Company (half of it) following the combined assaults led by Crazy Horse, White Bull, Hump, Gall, and others.

The men on Weir Ridge were attacked by natives,[67] increasingly coming from the apparently concluded Custer engagement, forcing all seven companies to return to the bluff before the pack train had moved even a quarter mile (400 m).

The intent may have been to relieve pressure on Reno's detachment (according to the Crow scout Curley, possibly viewed by both Mitch Bouyer and Custer) by withdrawing the skirmish line into the timber near the Little Bighorn River.

Had the U.S. troops come straight down Medicine Tail Coulee, their approach to the Minneconjou Crossing and the northern area of the village would have been masked by the high ridges running on the northwest side of the Little Bighorn River.

The Lakota asserted that Crazy Horse personally led one of the large groups of warriors who overwhelmed the cavalrymen in a surprise charge from the northeast, causing a breakdown in the command structure and panic among the troops.

One 7th Cavalry trooper claimed to have found several stone mallets consisting of a round cobble weighing 8–10 pounds (about 4 kg) with a rawhide handle, which he believed had been used by the Indian women to finish off the wounded.

Reno credited Benteen's luck with repulsing a severe attack on the portion of the perimeter held by Companies H and M.[note 5] On June 27, the column under General Terry approached from the north, and the natives drew off in the opposite direction.

Traveling night and day, with a full head of steam, Marsh brought the steamer downriver to Bismarck, Dakota Territory, making the 710 mi (1,140 km) run in the record time of 54 hours and bringing the first news of the military defeat which came to be popularly known as the "Custer Massacre".

[109] Ownership of the Black Hills, which had been a focal point of the 1876 conflict, was determined by an ultimatum issued by the Manypenny Commission, according to which the Sioux were required to cede the land to the United States if they wanted the government to continue supplying rations to the reservations.

[132] The historian James Donovan believed that Custer's dividing his force into four smaller detachments (including the pack train) can be attributed to his inadequate reconnaissance; he also ignored the warnings of his Crow scouts and Charley Reynolds.

"[179] Custer's highly regarded guide, "Lonesome" Charley Reynolds, informed his superior in early 1876 that Sitting Bull's forces were amassing weapons, including numerous Winchester repeating rifles and abundant ammunition.

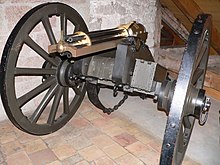

[197] Historian Mark Gallear claims that U.S. government experts rejected the lever-action repeater designs, deeming them ineffective in a clash with fully equipped European armies, or in case of an outbreak of another civil conflict.

[233] Writer Evan S. Connell noted in Son of the Morning Star:[234] Comanche was reputed to be the only survivor of the Little Bighorn, but quite a few Seventh Cavalry mounts survived, probably more than one hundred, and there was even a yellow bulldog.

A: Custer B: Reno C: Benteen D: Yates E: Weir