Battle of Moorefield

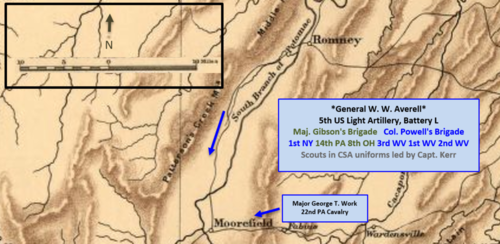

The fighting occurred along the South Branch of the Potomac River, north of Moorefield, West Virginia, in Hardy County.

On July 30, Confederate cavalry commanded by Brigadier General John McCausland moved north of the Potomac River and burned most of the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.

Those campsites were better suited for grazing their tired horses than they were for providing for the security of the troops—McCausland assumed that Averell's pursuing force was still 60 miles (97 km) away in Hancock, Maryland.

The disorganized Confederate force was no match for Averell's cavalry, which was armed with sabers, 6-shot revolvers (hand guns) and 7-shot repeating rifles.

Early's successes were a political liability for President Abraham Lincoln, and caused Union leaders to divert resources away from Richmond and West Virginia.

[5] Early, who had threatened the federal capital of Washington, D.C. during the first half of July, followed his Kernstown victory with an attack on northern territory.

[17] Averell rested his troops until August 3, when he received an order from General David Hunter to pursue McCausland and attack "wherever found".

McCausland established his headquarters at the Samuel McMechen home in Moorefield, leaving his brigade under the command of Colonel James A. Cochran from the 14th Virginia Cavalry.

[23] Johnson made his headquarters closer to his brigade at a mansion named Willow Wall that was owned by the McNeill family.

[23] Earlier, while the Confederates attempted to raid New Creek, Averell's force crossed the Potomac at Hancock, Maryland, and headed for Springfield, West Virginia, north of Romney.

The scouts were led by Captain Thomas R. Kerr of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, and his men were selected specifically for this mission.

Many of the men would "lie down by the road side, bridle rein in hand, [and] snatch a few minutes of sleep" while waiting for the scouts to signal it was OK to continue.

From this action, the scouts learned the location of the next set of pickets—and quietly captured two more squads of rebels posted along the main road.

The 2nd West Virginia Cavalry was held in reserve, and also guarded the pickets that had been captured earlier in the pre-sunrise morning.

Further east, Major Work's 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry battalion was in place on the Wardensville Road and moving west toward Moorefield.

This left the 36th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, between Gibson's Brigade and General Johnson's headquarters at the McNeill house.

[Note 4] The 8th Virginia Cavalry had enough warning from the commotion that its colonel ordered the men to horse, and they formed a line of battle.

"[39] This was a disadvantage in cavalry warfare, and Johnson's men were insufficiently armed for close combat with one-shot muskets.

However, the arrest was revoked a short time later, and Peters led the rear guard when they left the burning town.

[40] He performed relatively well at Moorefield, leading portions of his regiment while they slowed the Federal advance on the south side of the river.

The 14th Virginia Cavalry, commanded by Captain Edwin E. Bouldin, was the portion of McCausland's Brigade camped closest to the ford where the road crossed the river.

Bouldin faced a mob of men crossing the river that consisted of a mix of Union and Confederate soldiers.

Major Seymour B. Conger of the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry led the attack across the river on the east side of the main road.

[Note 6] Conger's 3rd West Virginia turned eastward and pursued rebels fleeing east down the road to Wardensville and Winchester.

[44] The two West Virginia regiments continued to pursue the Confederates down the road, and captured McCausland's two pieces of artillery.

[29] Those captured were probably stragglers found by McNeill's rangers, who operated in the Moorefield area and chose not to camp with McCausland's brigades.

He reported that "Highway robbery of watches and pocket-books was of ordinary occurrence; the taking of breast-pins, finger-rings, and ear-rings frequently happened.

A soldier of an advance guard robbed of his gold watch the Catholic clergyman of Hancock on his way from church on Sunday...."[51] Moorefield was another major victory for Averell, who typically did well when operating on his own, but had difficulty with direct supervision where he was expected to work in concert with others.

He had already scored victories at Droop Mountain and Rutherford's Farm, and was one of the few Union cavalry leaders that achieved success in the east before the arrival of General Philip Sheridan.

[53] Major Theodore F. Lang, from the 6th West Virginia Cavalry, wrote that the "fight was one of the most signal victories for the Union cause during the war".