Battle of New Orleans

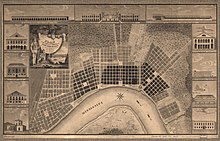

1813 1814 1815 East Coast Great Lakes / Saint Lawrence River West Indies / Gulf Coast Pacific Ocean The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815, between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson,[4] roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the French Quarter of New Orleans,[8] in the current suburb of Chalmette, Louisiana.

[11][note 3] Prior to that, in August 1814, Vice Admiral Cochrane had convinced the Admiralty that a campaign against New Orleans would weaken American resolve against Canada and hasten a successful end to the war.

[23] Andrew Lambert notes that Keane squandered a passing opportunity to succeed, when he decided to not take the open road from the Rigolets to New Orleans by way of Bayou Chef Menteur.

[28][23][26] On the morning of December 23, Keane and a vanguard of 1,800 British soldiers reached the east bank of the Mississippi River, 9 miles (14 km) south of New Orleans.

[32] The British invaded the home of Major Gabriel Villeré, but he escaped through a window[33] and hastened to warn General Jackson of the approaching army and the position of their encampment.

[34] Following Villeré's intelligence report, on the evening of December 23, Jackson led 2,131[36] men in a brief three-pronged assault from the north on the unsuspecting British troops, who were resting in their camp.

[note 8] Historian Robert Quimby states that the British won a "tactical victory, which enabled them to maintain their position",[41] but they "were disabused of their expectation of an easy conquest".

After yet another failure to breach Line Jackson Pakenham decided to wait for his entire force of 8,000 men to assemble before continuing his attack (the 40th Foot arrived too late, disembarking on 12 January 1815.

[54] The start of the battle was marked by the launch of a signal rocket[55] at 6:20am, soon after followed by artillery fire from the British lines towards Jackson's headquarters at the McCarty house.

[59] Preparations for the attack had floundered early on January 8, as the canal collapsed and the dam failed, leaving the sailors to drag the boats through the mud with Thornton's right bank assault force.

[73] Reilly felt the fault lay with Morgan, who had dispersed his troops, rather than concentrating most of them around his main defence, whilst deploying a picket, to give advance warning once the British arrived.

[81][note 20] Carson Ritchie goes as far to assert that 'it was not Pakenham, but Sir Alexander Dickson who lost the third battle of New Orleans' in consequence of his recommendation to evacuate the Right Bank,[81] and that 'he could think of nothing but defense'.

[89] The 44th Regiment of Foot was assigned by General Edward Pakenham to be the advance guard for the first column of attack on 8 January 1815, and to carry the fascines and ladders which would enable the British troops to cross the ditch and scale the American ramparts.

[98] Within a few minutes, the American 7th US Infantry arrived, moved forward, and fired upon the British in the captured redoubt; within half an hour, Rennie and nearly all of his men were dead.

[note 23] A reduction in headcount due to 443 British soldiers' deaths since the prior month was reported on January 25, which is lower than Hayne's estimate of 700 for the battle alone.

[110] The failure of the British to have breached the parapet and conclusively eliminated the first line of defense was to result in high casualties as successive waves of men marching in column whilst the prepared defenders were able to direct their fire into a Kill zone, hemmed in by the riverbank and the swamp.

[114] Almost universal blame was assigned to Colonel Mullins of the 44th Foot which had been detailed to carry fascines and ladders to the front to enable the British soldiers to cross the ditch and scale the parapet and fight their way to the American breastwork.

[note 24] Pakenham learned of Mullins' conduct and placed himself at the head of the 44th, endeavoring to lead them to the front with the implements needed to storm the works, when he fell wounded after being hit with grapeshot.

It has been observed that Keane's failure, to have taken the Chef Menteur Road, was compounded when the aggressively natured Pakenham went ahead and launched a frontal assault before the vital flank operation on the other bank of the river had been completed, at a cost of over 2,000 casualties.

With Britain having ratified the treaty and the United States having resolved that hostilities should cease pending imminent ratification, the British departed, sailing to the West Indies.

Dominique and Belluche, and the Lafitte brothers, all of the Barataria privateers; of General Garrique de Flanjac, a State Senator, and brigadier of militia, who served as a volunteer; of Majors Plauche, Sainte-Geme.

According to Matthew Warshauer, the Battle of New Orleans meant, "defeating the most formidable army ever arrayed against the young republic, saving the nation's reputation in the War of 1812, and establishing [Jackson] as America's preeminent hero.

[154] The amoral depravity of the British, in contrast with the wholesome behavior of the Americans, has the "beauty and booty" story at the center of a popular history account of Jackson's victory at New Orleans.

[160] In keeping with the idea of the conflict as a "second war of independence" against John Bull, the narrative of the skilled rifleman in the militia had parallels with the myth of the Minuteman as the key factor in winning against the British.

[7] Although there are contemporary secondary sources that champion the riflemen as the cause of this victory,[166] Ritchie notes the British reserve was 650 yards away from the American line, so never came within rifle range, yet suffered 182 casualties.

[171] The engineers who oversaw the erection of the ramparts, the enslaved persons of color who built them, and the trained gunners who manned the cannons have seen their contributions understated as a consequence of these popular histories that have been written since the Era of Good Feelings.

[161] Popular memory's omissions of the numerous artillery batteries, professionally designed earthworks, and the negligible effect of aimed rifle fire during that battle lulled those inhabitants of the South into believing that war against the North would be much easier than it really would be.

[176] There are still those who are happy to cling to accounts of forefathers from their state, and how the "long riflemen killed all of the officers ranked Captain and above in this battle,"[177] and "Victory was made possible by an unlikely combination of oddly disparate forces, British logistic oversights and tactical caution, and superior American backwoods marksmanship.

By the time the Federalist "ambassadors" got to Washington, the war was over and news of Andrew Jackson's stunning victory in the Battle of New Orleans had raised American morale immensely.

Prior to the twentieth century the British government commonly commissioned and paid for statues of fallen generals and admirals during battles to be placed inside St Paul's Cathedral in London as a memorial to their sacrifices.