Siege of Fort Ticonderoga (1777)

These movements precipitated the occupying Continental Army, an under-strength force of 3,000 under the command of General Arthur St. Clair, to withdraw from Ticonderoga and the surrounding defenses.

Burgoyne's army occupied Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence, the extensive fortifications on the Vermont side of the lake, without opposition on 6 July.

The delay required by the British to build their fleet on Lake Champlain caused General Guy Carleton to hold off on attempting an assault on Ticonderoga in 1776.

[7] General John Burgoyne arrived in Quebec in May 1777 and prepared to lead the British forces assembled there south with the aim of gaining control of Ticonderoga and the Hudson River valley, dividing the rebellious provinces.

[13] While en route, Burgoyne authored a proclamation to the Americans, written in the turgid, pompous style for which he was well-known, and frequently criticized and parodied.

A war council held by Generals St. Clair and Schuyler on 20 June concluded that "the number of troops now at this post, which are under 2,500 effectives, rank and file, are greatly inadequate to the defense", and that "it is prudent to provide for a retreat".

[19] It was believed to be impossible for the British to place cannons on the heights, even though Trumbull, Anthony Wayne, and an injured Benedict Arnold climbed to the top and noted that gun carriages could probably be dragged up.

[20] The defence, or lack thereof, of Sugar Loaf was complicated by the widespread perception that Fort Ticonderoga, with a reputation as the "Gibraltar of the North", had to be held.

[16] Neither abandoning the fort nor garrisoning it with a small force (sufficient to respond to a feint but not to an attack in strength) was viewed as a politically viable option.

[21] Furthermore, George Washington and the Congress were of the opinion that Burgoyne, who was known to be in Quebec, was more likely to strike from the south, moving his troops by sea to New York City.

Schuyler took command of a reserve force of 700 at Albany, and Washington ordered four regiments to be held in readiness at Peekskill, further down the Hudson River.

[24] On the morning of 2 July, St. Clair decided to withdraw the men occupying the defence post at Mount Hope, which was exposed and subject to capture.

[26] British engineers discovered the strategic position of Sugar Loaf, and realized that the American withdrawal from Mount Hope gave them access to it.

[25] Starting on 2 July, they began clearing and building gun emplacements on top of that height, working carefully to avoid notice by the Americans.

[28] That night the British lost their element of surprise when some Indians lit fires on Sugar Loaf, alerting the Americans to their presence there.

[29] All possible armaments, as well as invalids, camp followers, and supplies were loaded onto a fleet of more than 200 boats that began to move up the lake toward Skenesboro, accompanied by Colonel Pierse Long's regiment.

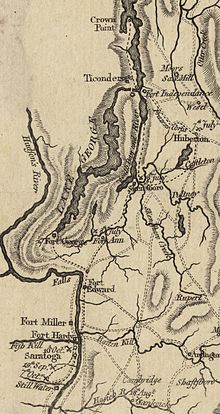

[34] The British pursuit resulted in the Battle of Hubbardton when they caught up with the rear guard on the morning of 7 July, but this enabled the main American body to escape, eventually joining forces with Schuyler at Fort Edward.

[37] He then encountered delays in traveling the heavily wooded road between Skenesboro and Fort Edward, which General Schuyler's forces had effectively ruined by felling trees across it and destroying all its bridges in the swampy terrain.

[39] General Gates reported to Governor George Clinton on 20 November that Ticonderoga and Independence had been abandoned and burned by the retreating British.

John Adams wrote, "I think we shall never be able to defend a post until we shoot a general", and George Washington said it was "an event of chagrin and surprise, not apprehended nor within the compass of my reasoning".

[41] Schuyler was eventually removed as commander of the Northern Department, replaced by General Gates; the fall of Ticonderoga was among the reasons cited.