Battle of Vercellae

[4] In 113 BC, a large migrating Germanic-Celtic alliance headed by the Cimbri and the Teutones entered the Roman sphere of influence.

They invaded Noricum (located in present-day Austria and Slovenia) which was inhabited by the Taurisci people, friends and allies of Rome.

The Senate commissioned Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, one of the consuls, to lead a substantial Roman army to Noricum to force the barbarians out.

An engagement, later called the battle of Noreia, took place, in which the invaders completely overwhelmed the Roman Legions and inflicted a devastating loss on them.

He met the Cimbri approximately 100 miles north of Arausio where a battle[clarification needed] was fought and the Romans suffered another humiliating defeat.

He first fought the Cimbri and their Gallic allies the Volcae Tectosages just outside Tolosa, and despite the huge number of tribesmen, the Romans routed them.

The Battle of Burdigala destroyed the Romans' hopes of definitively defeating the Cimbri and so the Germanic threat continued.

[7] In 106 BC the Romans sent their largest army yet; the senior consul of that year, Quintus Servilius Caepio, was authorized to use eight legions in an effort to end the Germanic threat once and for all.

The Romans sent the senior consul of that year, Gaius Marius, a proven and capable general, at the head of another large army.

[11] Meanwhile, Marius had completely defeated the Ambrones and the Teutones in a battle near Aquae Sextiae in Transalpine Gaul.

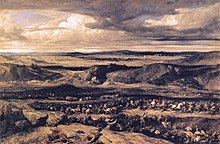

In 101 BC the armies of Marius and Catulus joined forces and faced the Germanic invaders in Galia Cisalpina (Italian Gaul).

Neither side genuinely sought negotiations; the Romans not intending to hand over their land to foreign invaders and the Cimbri believing themselves to be the superior force.

)[15][16][17][18] Marius and Catulus had stationed their army in a defensible position near the River Po, to prevent the Cimbri from moving into Italy.

'[20] The Cimbri did not understand, therefore, Marius produced a number of captive Teutonic kings, possibly including Teutobod, from a nearby tent.

The Cimbric king, Boiorix, convinced his people to fight the Romans as soon as possible as he wanted to settle the conflict sooner rather than later.

[23] Traditionally, most historians locate the site of the battle in or near the modern Vercelli, Piedmont, in northern Italy.

Marius had also very sensibly formed up his lines facing west, therefore the Cimbri had to fight with the morning sun in their eyes.

When they reached the Cimbri they threw their pila into their disorganized ranks, the legionaries drew their swords and were soon in hand-to-hand combat.

The battle became a rout, stopped by the wagons drawn up (as was customary among Germanic and Celtic peoples) at the rear of the battlefield.

[32] The victory of Vercellae, following close on the heels of Marius' destruction of the Teutones at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae the previous year, put an end to the Germanic threat to Rome's northern frontiers.

The Cimbri were virtually wiped out, with Marius claiming to have killed 100,000 warriors and capturing and enslaving many thousands, including large numbers of women and children.

Although Marius, riding a wave of popularity after the Vercellae victory, was elected consul (for 100 BC) again, his political opponents exploited this.

Immediately after the battle Marius granted Roman citizenship to his Italian allied forces without consulting or asking permission from the Senate first.

And Julius Caesar, when ordered by the Senate to lay down his command and return to Rome to face misconduct charges, would instead lead one of his legions across the Rubicon in 49 BC.

Roman victories.

Roman victories.

Cimbri and Teutons victories.

Cimbri and Teutons victories.