Battle of Wood Lake

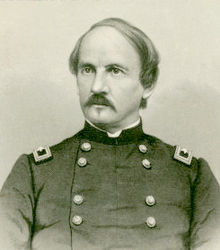

The two-hour battle, which actually took place at nearby Lone Tree Lake, was a decisive victory for the U.S. forces led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley.

[2]: 187 In early September 1862, the U.S. defeat at the Battle of Birch Coulee and the sieges at Hutchinson, Forest City and Fort Abercrombie caused further panic, as the exodus of Minnesota settlers continued.

Pope, anxious to vindicate himself following his defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run, proceeded to put pressure on Sibley to move forcefully against the Dakota, but struggled to secure more troops to support the war effort.

[2] Famished, it was no wonder that several members of the "unruly" 3rd Minnesota Infantry Regiment were tempted to forage for potatoes at the Upper Sioux Agency on the morning on September 23, unwittingly triggering what came to be known as the Battle of Wood Lake.

[5] After the Battle of Birch Coulee, Colonel Sibley had left a message for Little Crow in a cigar box attached to a stake in the battleground,[6] opening a dialogue between the two camps.

In a letter written for him by Antoine Joseph Campbell around September 10,[2]: 178 Little Crow hinted to Sibley that he might be willing to negotiate the release of the "one hundred and fifty-five prisoners" whom they had treated "just as well as us.

[7] Unbeknownst to Little Crow, a few Mdewakanton chiefs including Wabasha, Wakute and Taopi had managed to smuggle a separate letter to Sibley, voicing their opposition to the war and offering their assistance.

Little Crow's camp crier announced rewards for anyone bringing back the scalps of Sibley, Joseph R. Brown, William H. Forbes, Louis Robert or Nathan Myrick, or the American flag.

"[10] He proceeded to argue that Sibley's army could be taken easily if they surrounded the camp under the cover of darkness[6] and stated, "I have just been to the edge of the bluff and looked over and saw to my astonishment but a few tipis there; only five officers' tents.

"[10] However, Gabriel Renville (Tiwakan) and Solomon Two Stars, two leaders from the "friendly" Dakota camp who had refused to participate in previous battles, argued vehemently against the plan.

[14] His plan for the following day was to "cross the wooded Yellow Medicine River valley and go to the ruined Upper Sioux Agency using the Government Road.

"[14] The Dakota battle plan was to attack Sibley's troops as they were marching a mile or more to the northwest of the lake, along the road leading to the Upper Sioux Agency.

The 270 men of the 3rd Minnesota in his command had suffered an embarrassing defeat by the Confederates in the First Battle of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, on July 13, 1862, when Colonel Henry C. Lester had decided to surrender instead of going to the aid of one of their detachments which had been attacked.

[5] Ezra T. Champlin, who fought in the battle as a non-commissioned officer, later conceded, "I may as well state here that the Third, galled by a humiliating surrender at Murfreesborough, Tenn., by a recreant and cowardly commander, had lost in a great measure their former high discipline, and were quite unruly, anxious only to redeem in the field their wounded honor.

"[16] The 3rd Minnesota Infantry Regiment had acquired potatoes as they had passed through farmland at the Lower Sioux Agency, and had nearly run out by the time they reached Lone Tree Lake.

[5][16][4] Big Eagle explained that some of the wagons were not on the road, and were headed straight at the Dakota warriors as they lay waiting in the grass; the men in position had no choice but to get up and fire to avoid being run over.

Not waiting for orders from Sibley, Major Abraham E. Welch led 200 men of the 3rd Minnesota Infantry Regiment to the right of the initial attack and toward the Dakota forces, which were quickly gathering in number.

[5] Captain Ezra T. Champlin recalled, "Our thorough drill in the South showed here to good advantage; our skirmish line moved steadily forward, firing rapidly, forcing the enemy back toward the bluffs of the Minnesota river.

"[16] From the standpoint of the reserve, he could see that the Dakota warriors "formed a semi-circle in our front, and to right and left, moving about with great activity, howling like demons, firing and retreating, their quick movements seeming to multiply their numbers.

[16] Once they had retreated back across the creek, the men of the 3rd Minnesota Infantry Regiment were joined by forty Renville Rangers, a unit of "nearly all mixed-bloods"[2]: 185 under Lieutenant James Gorman, sent by Sibley to reinforce them.

Sibley's men made a stand on the plateau between the ravine and the camp, with the Dakota warriors "taking advantage of the low hills bordering the narrow intervals along the creek.

Marshall stated in his report, "Gradually advancing the line, the men keeping close to the ground and firing as they crawled forward, I gained a good position from which to charge the Indians.

[17] On the extreme left, Sibley ordered Major Robert N. McLaren with Company F from the 6th Regiment under Captain Horace B. Wilson to "double-quick around the south side of the little lake near the camp, and take possession of a ridge overlooking a ravine"[19] about one mile away, where a large number of Dakota were positioned for a flanking attack.

After the battle on September 23, 1862, Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley wrote in a letter to his wife that the Dakota had received "a severe blow" and that he was confident they "will not dare to make another stand.

"[3] The battle marked the end of organized warfare for the Dakota in Minnesota, although conflict would continue the following year as Sibley pursued the Sioux leaders who had fled north.

[3][4][24] The adjutant general of Minnesota, in his official report after the battle, stated: "As the hottest of the enemy's fire was borne by the Third Regiment and the Renville Rangers, the heaviest part of the loss was confined to those troops.

[26][27] Iron Walker (Mazomani), a Wahpeton Dakota who had been an advocate of peace, had tried to cross over to Simon Anawangmani carrying a flag of truce during the fighting, but his leg was blown off by a cannonball.

[8] The number had been determined by counting sticks which had been handed out to each warrior on the road leading to the battleground, which were then collected at "Yellow Medicine bottoms," a few miles from where the battle took place.

"[2]: 182 Furthermore, at the conclusion of the war council on September 22, Gabriel Renville quietly sent word for the "friendly" Dakota who did not actually intend to fight to gather in a ravine further west,[10][9] where they slept.

[9][6][20] Of the Dakota who remained with Little Crow's forces, Chief Big Eagle estimated that "hundreds" did not get involved or fire a single shot during the actual battle, simply because they were too far out.