Battle of Monte Cassino

In the beginning of 1944, the western half of the Winter Line was anchored by German forces holding the Rapido-Gari, Liri, and Garigliano valleys and several surrounding peaks and ridges.

Although in the east the German defensive line had been breached on the Adriatic front and Ortona was captured by the 1st Canadian Division, the advance had ground to a halt with the onset of winter blizzards at the end of December, making close air support and movement in the jagged terrain impossible.

Excellent observation from the peaks of several hills allowed the German defenders to detect Allied movement and direct highly accurate artillery fire, preventing any northward advance.

The main central thrust by the U.S. II Corps would commence on 20 January with the U.S. 36th Infantry Division making an assault across the swollen Gari river five miles (8.0 km) downstream of Cassino.

Simultaneously, the French Expeditionary Corps (CEF) led by General Alphonse Juin would continue its "right hook" move towards Monte Cairo, the hinge to the Gustav and Hitler defensive lines.

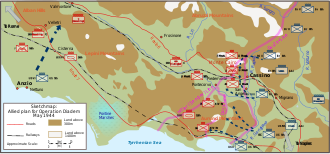

In truth, Clark did not believe there was much chance of an early breakthrough,[13] but he felt that the attacks would draw German reserves away from the Rome area in time for the attack on Anzio (codenamed Operation Shingle) where the U.S. VI Corps (British 1st and U.S. 3rd Infantry Divisions, the 504th Parachute Regimental Combat Team, U.S. Army Rangers and British Commandos, Combat Command 'B' of the U.S. 1st Armored Division, along with supporting units), under Major General John P. Lucas, was due to make an amphibious landing on 22 January.

However, there would certainly have been time to alter the overall battle plan and cancel or modify the central attack by the U.S. II Corps to make men available to force the issue in the south before the German reinforcements were able to get into position.

Rick Atkinson described the intense German resistance: Artillery and Nebelwerfer drumfire methodically searched both bridgeheads, while machine guns opened on every sound ... GIs inched forward, feeling for trip wires and listening to German gun crews reload ... to stand or even to kneel was to die ... On average, soldiers wounded on the Rapido received "definitive treatment" nine hours and forty-one minutes after they were hit, a medical study later found ..."[17]The assault had been a costly failure, with the 36th Division losing 2,100[18] men killed, wounded and missing in 48 hours.

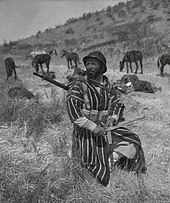

On the right, the Moroccan-French troops made strategical initial progress against the German 5th Mountain Division, commanded by General Julius Ringel, gaining positions on the slopes of their key objective, Monte Cifalco.

This view is supported by the inability of Major General Lucian Truscott, commanding the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, as related below, to get hold of him for discussions at a vital juncture of the Anzio breakout at the time of the fourth Cassino battle.

"[27][nb 1] U.S. II Corps commander Geoffrey Keyes flew over the monastery several times and reported to Fifth Army G-2 that he had not seen evidence of German troops in the abbey.

It was impossible to ask troops to storm a hill surmounted by an intact building such as this, capable of sheltering several hundred infantry in perfect security from shellfire and ready at the critical moment to emerge and counter-attack. ...

Indeed, sixteen bombs hit the Fifth Army compound at Presenzano, 17 miles (27 km) from Monte Cassino, and exploded only yards away from the trailer where Clark was doing paperwork at his desk.

Only about 40 people remained: the six monks who survived in the deep vaults of the abbey; their 79-year-old abbot, Gregorio Diamare; three tenant farmer families; orphaned or abandoned children; the badly wounded; and the dying.

[nb 2] Following its destruction, paratroopers of the German 1st Parachute Division then occupied the ruins of the abbey and turned it into a fortress and observation post, which became a serious problem for the attacking Allied forces.

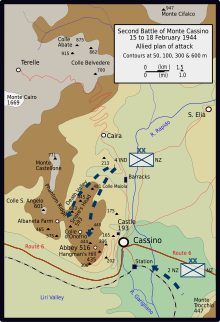

In the other half of the main assault, the two companies from the 28th (Māori) Battalion from the New Zealand Division forced a crossing of the Rapido and attempted to gain the railway station in Cassino town.

With the aid of a nearly constant smoke screen laid down by Allied artillery that obscured their location from the German batteries on Monastery Hill, the Māori were able to hold their positions for much of the day.

[54] After the war, regarding the second battle, Senger admitted that when he was contemplating the prospects of a renewed frontal assault on Cassino that "what I feared even more was an attack by Juin's corps with its superb Moroccan and Algerian divisions".

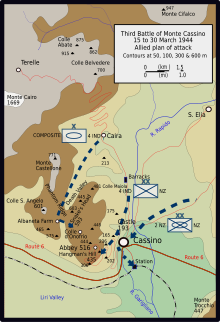

The "right hook" in the mountains had also been a costly failure, and it was decided to launch twin attacks from the north along the Rapido valley: one towards the fortified Cassino town and the other towards Monastery Hill.

The British 78th Infantry Division, which had arrived in late February and been placed under the command of the New Zealand Corps, would then cross the Rapido downstream of Cassino and start the push to Rome.

Nevertheless, success was there for the New Zealanders' taking, but by the time a follow-up assault on the left had been ordered that evening, it was too late: defences had been reorganised, and more critically, the rain, contrary to forecast, had started again.

The U.S. 36th Division was sent on amphibious assault training, and road signposts and dummy radio traffic were created to give the impression that a seaborne landing was being planned for north of Rome.

In the mountains above Cassino, the aptly named Mount Calvary (Monte Calvario, or Point 593 on Snakeshead Ridge) was taken by the Polish 2nd Corps, under the command of General Władysław Anders, only to be recaptured by German paratroopers.

[citation needed] In the early morning hours of 12 May, the Polish infantry divisions were met with "such devastating mortar, artillery and small-arms fire that the leading battalions were all but wiped out".

A single armoured division, the 26th Panzer, was in transit from north of the Italian capital of Rome, where it had been held anticipating the nonexistent seaborne landing the Allies had faked and so was unavailable to fight.

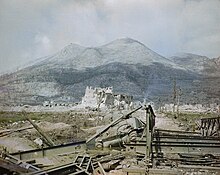

[90] In the course of the battles, the ancient abbey of Monte Cassino, where St. Benedict in AD 516 first established the Rule that ordered monasticism in the west, was entirely destroyed by Allied bombing and artillery barrages in February 1944.

[nb 6] Some months earlier, in the Italian autumn of 1943, two officers in the Hermann Göring Panzer Division, Captain Maximilian Becker and Lieutenant Colonel Julius Schlegel, proposed the removal of Monte Cassino's treasures to the Vatican and Vatican-owned Castel Sant'Angelo ahead of the approaching front.

"[96] After a mass in the basilica, Abbot Gregorio Diamare [it] formally presented signed parchment scrolls in Latin to General Paul Conrath, to tribuno militum Julio Schlegel and to Maximiliano Becker medecinae doctori "for rescuing the monks and treasures of the Abbey of Monte Cassino".

The Commonwealth War Graves cemetery on the western outskirts of Cassino is a burial place for British, New Zealand, Canadian, Indian, Gurkha, Australian, and South African casualties.

In the 1950s, a subsidiary of the Pontificia Commissione di Assistenza distributed Lamps of Brotherhood, cast from the bronze doors of the destroyed Abbey, to representatives of nations that had served on both sides of the war to promote reconciliation.