German Peasants' War

In Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants, Luther condemned the violence as the devil's work and called for the aristocrats to put down the rebels like mad dogs.

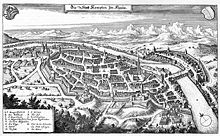

Aristocratic dynasties ruled hundreds of largely independent territories (both secular and ecclesiastical) within the framework of the empire, and several dozen others operated as semi-independent city-states.

By maintaining the remnants of the ancient law which legitimized their own rule, they not only elevated their wealth and position in the empire through the confiscation of all property and revenues, but increased their power over their peasant subjects.

However, it was precisely on this same theological foundation that Müntzer's ideas briefly coincided with the aspirations of the peasants and plebeians of 1525: viewing the uprising as an apocalyptic act of God, he stepped up as 'God's Servant against the Godless' and took his position as leader of the rebels.

[16] To the degree that other classes, such as the bourgeoisie,[18] might gain from the centralization of the economy and the elimination of the lesser nobles' territorial controls on manufacture and trade,[19] the princes might unite with the burghers on the issue.

The town patricians were increasingly criticized by the growing burgher class, which consisted of well-to-do middle-class citizens who held administrative guild positions or worked as merchants.

[26] F. Engels cites: "To the call of Luther of rebellion against the Church, two political uprisings responded, first, the one of lower nobility, headed by Franz von Sickingen in 1523, and then, the great peasant's war, in 1525; both were crushed, because, mainly, of the indecisiveness of the party having most interest in the fight, the urban bourgeoisie".

[citation needed] The Swabian League fielded an army commanded by Georg, Truchsess von Waldburg, later known as "Bauernjörg" for his role in the suppression of the revolt.

At the beginning of the revolt the league members had trouble recruiting soldiers from among their own populations (particularly among peasant class) due to fear of them joining the rebels.

The landsknechte clothed, armed and fed themselves, and were accompanied by a sizable train of sutlers, bakers, washerwomen, prostitutes and sundry individuals with occupations needed to sustain the force.

[27] The use of the landsknechte in the German Peasants' War reflects a period of change between traditional noble roles or responsibilities towards warfare and practice of buying mercenary armies, which became the norm throughout the 16th century.

This sometimes meant producing supplies for their opponents, such as in the Archbishopric of Salzburg, where men worked to extract silver, which was used to hire fresh contingents of landsknechts for the Swabian League.

[37] Their attempt to break new ground was primarily seeking to increase their liberty by changing their status from serfs,[38] such as the infamous moment when the peasants of Mühlhausen refused to collect snail shells around which their lady could wind her thread.

The so-called Book of One Hundred Chapters, for example, written between 1501 and 1513, promoted religious and economic freedom, attacking the governing establishment and displaying pride in the virtuous peasant.

Luther vehemently opposed the revolts, writing the pamphlet Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants, in which he remarks "Let everyone who can, smite, slay, and stab, secretly or openly ... nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful, or devilish than a rebel.

Historian Roland Bainton saw the revolt as a struggle that began as an upheaval immersed in the rhetoric of Luther's Protestant Reformation against the Catholic Church but which really was impelled far beyond the narrow religious confines by the underlying economic tensions of the time.

Other demands of the Twelve Articles included the abolition of serfdom, death tolls, and the exclusion from fishing and hunting rights; restoration of the forests, pastures, and privileges withdrawn from the community and individual peasants by the nobility; and a restriction on excessive statute labor, taxes and rents.

The detached troops encountered a separate group of 1,200 peasants engaged in local requisitions, and entered into combat, dispersing them and taking 250 prisoners.

After taking the count as their prisoner, the peasants forced him, and approximately 70 other nobles who had taken refuge with him, to run the gauntlet of pikes, a popular form of execution among the landsknechts.

On 15 May joint troops of Landgraf Philipp I of Hesse and George, Duke of Saxony defeated the peasants under Müntzer near Frankenhausen in the County of Schwarzburg.

The next day Philip's troops united with the Saxon army of Duke George and immediately broke the truce, starting a heavy combined infantry, cavalry and artillery attack.

Upon identifying two squadrons of League and Alliance horse approaching on each flank, now recognized as a dangerous Truchsess strategy, they redeployed the wagon-fort and guns to the hill above the town.

Several other bands arrived, bringing the total to 18,000, and within a matter of days, the city was encircled and the peasants made plans to lay a siege.

The peasant movement failed, with cities and nobles making a separate peace with the princely armies that restored the old order in a frequently harsher form, under the nominal control of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, represented in German affairs by his younger brother Ferdinand.

[64] While Landsknechts, professional soldiers, and knights, joined the peasants in their efforts (albeit in fewer numbers), the Swabian League had a better grasp of military technology, strategy, and experience.

He wrote, "Three centuries have passed and many a thing has changed; still the Peasant War is not so impossibly far removed from our present struggle, and the opponents who have to be fought are essentially the same.

It suggested that in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, peasants saw newly achieved economic advantages slipping away, to the benefit of the landed nobility and military groups.

Using sources such as letters, journals, religious tracts, city and town records, demographic information, family and kinship developments, historians challenged long-held assumptions about German peasants and the authoritarian tradition.

[19] For Blickle, the rebellion required a parliamentary tradition in southwestern Germany and the coincidence of a group with significant political, social and economic interest in agricultural production and distribution.

[73][74] The new studies of localities and social relationships through the lens of gender and class showed that peasants were able to recover, or even in some cases expand, many of their rights and traditional liberties, to negotiate these in writing, and force their lords to guarantee them.